My Great-Great-Grandfather Hated the Gettysburg Address. Now He’s Famous For It

It’s hard to imagine anyone could pan Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address, but one cantankerous reporter did just that

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Gettysburg-address-review-631.jpg)

Late last week, the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, newspaper, now called the Patriot-News, issued a tongue-in-cheek retraction of its 150-year-old snub of President Abraham Lincoln’s heralded Gettysburg Address. The editorial page informed its readers:

"Seven score and ten years ago, the forefathers of this media institution brought forth to its audience a judgment so flawed, so tainted by hubris, so lacking in the perspective history would bring, that it cannot remain unaddressed in our archives."

The editors mused that their predecessors had likely been “under the influence of partisanship, or of strong drink.” Waiving the statute of limitations, the newspaper ended its announcement in time-honored fashion: “The Patriot-News regrets the error.” The news was picked up by a wide swath of publications, but none were more surprising than the appearance of a “Jebidiah Atkinson” on “Saturday Night Live:”

But of course there was no “Jebidiah Atkinson.” The author of the thumbs-down review was Oramel Barrett, editor of what was then called the Daily Patriot and Union. He was my great-great-grandfather.

The “few appropriate remarks” President Abraham Lincoln was invited to deliver at the dedication of a national cemetery in Gettysburg are remembered today as a masterpiece of political oratory. But that’s not how Oramel viewed them back in 1863.

“We pass over the silly remarks of the President,” he wrote in his newspaper. “For the credit of the nation, we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.”

My ancestor’s misadventure in literary criticism has long been a source of amusement at family gatherings (and now one for the entire nation.) How could the owner-editor of a daily in a major state capital have been so utterly tone deaf about something this momentous?

Oddly enough, Oramel’s put-down of the Gettysburg Address—though a minority view in the Union at the time—didn’t stand out as especially outrageous at the time. Reaction to the speech was either worshipful or scornful, depending on one’s party affiliation. The Republicans were the party of Lincoln, while the Democrats were the more or less loyal opposition (though their loyalty was often questioned).

Here’s the Chicago Times, a leading Democratic paper: “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly flat dishwatery utterances of a man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States.”

It wasn’t just the Democrats. Here’s the Times of London: “The ceremony was rendered ludicrous by some of the sallies of that poor President Lincoln.”

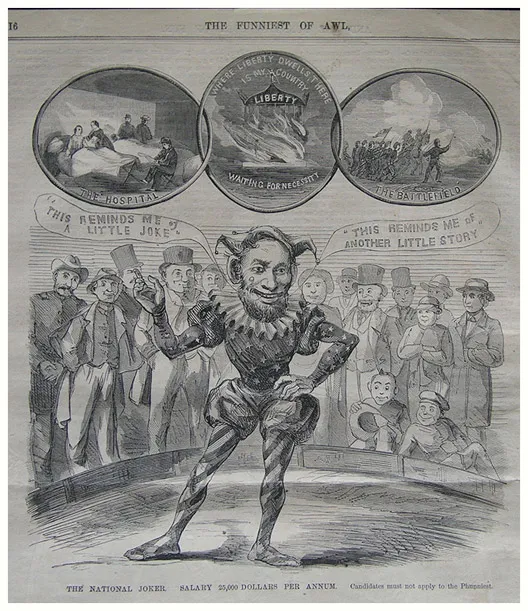

In the South, naturally, Lincoln was vilified as a bloodthirsty tyrant. But his opponents in the North could be almost as harsh. For years, much of the Democratic press had portrayed him as an inept, awkward, nearly illiterate bumpkin who surrounded himself with sycophants and responded to crises with pointless, long-winded jokes. My ancestor’s newspaper routinely referred to Lincoln as “the jester.”

Like Oramel Barrett, those who loathed Lincoln the most belonged to the radical wing of the Democratic Party. Its stronghold was Pennsylvania and the Midwest. The radical Democrats were not necessarily sympathetic to the Confederacy, nor did they typically oppose the war—most viewed secession as an act of treason, after all. Horrified by the war’s gruesome slaughter, however, they urged conciliation with the South, the sooner the better.

To the Lincoln-bashers, the president was using Gettysburg to kick off his re-election campaign—and showing the poor taste to do so at a memorial service. According to my bilious great-great-grandfather, he was performing “in a panorama that was gotten up more for the benefit of his party than for the glory of the Nation and the honor of the dead.”

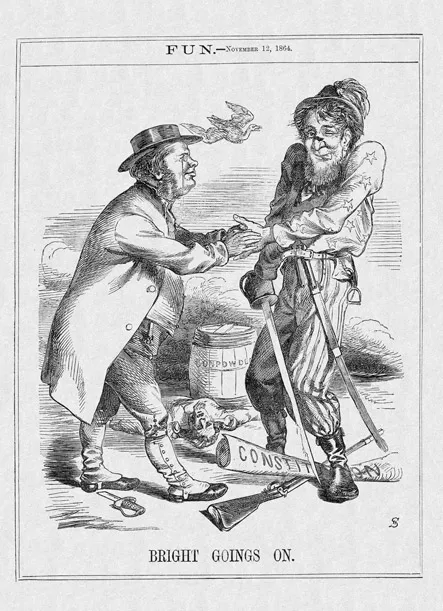

Worse, for Lincoln’s opponents, was a blatant flaw in the speech itself. In just 10 sentences, it advanced a new justification for the war. Indeed, its first six words—”Four score and seven years ago”—were enough to arouse the fury of Democratic critics.

A little subtraction shows that Lincoln was referring not to 1787, when the Constitution, with its careful outlining of federal rights and obligations (and tacit acceptance of slavery), was drawn up, but to 1776, when the signers of the Declaration of Independence had proclaimed that “all men are created equal.”

The Union war effort had always been aimed at defeating Southern states that had rebelled against the United States government. If white Southerners wanted to own black slaves, many in the North felt, that was not an issue for white Northern boys to die for.

Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation at the start of 1863. Now, at Gettysburg, he was following through, declaring the war a mighty test of whether a nation dedicated to the idea of personal liberty “shall have a new birth of freedom.” This, he declared, was the cause for which the thousands of Union soldiers slain here in July “gave the last full measure of devotion.” He was suggesting, in other words, that the troops had died to ensure that the slaves were freed.

To radical Northern Democratics, Dishonest Abe was pulling a bait-and-switch. His speech was “an insult” to the memories of the dead, the Chicago Times fumed: “In its misstatement of the cause for which they died, it was a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity cannot regard it as otherwise than willful.” Worse, invoking the Founding Fathers in his cause was nothing short of libelous. “They were men possessing too much self-respect,” the Times assured its readers, “to declare that negroes were their equals.”

Histories have generally played down the prevalence of white racism north of the Mason-Dixon Line. The reality was that Northerners, even Union soldiers battling the Confederacy, had mixed feelings about blacks and slavery. Many, especially in the Midwest, abhorred abolitionism, which they associated with sanctimonious New Englanders. Northern newspaper editors warned that truly freeing the South’s slaves and, worse, arming them would lead to an all-out race war.

That didn’t happen, of course. It took another year and a half of horrific fighting, but the South surrendered on the North’s terms—and by the time Lee met Grant at Appomattox in April 1865, both houses of Congress had passed the 13th Amendment, banning slavery. With Lincoln’s assassination just six days later, the criticism ceased. For us today, Lincoln is the face on Mount Rushmore, and the Gettysburg Address one of the greatest speeches ever delivered.

—————

Doug Stewart also wrote about his cantankerous great-great-grandfather, Oramel Barrett, in the November 2013 issue of America’s Civil War.