The Story Behind the Failed Minstrel Show at the 1964 World’s Fair

The integrated theatrical showcase had progressive ambitions but lasted only two performances

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/8c/748ca33b-1137-4f09-9c07-e6db131887fb/be062110edit.jpg)

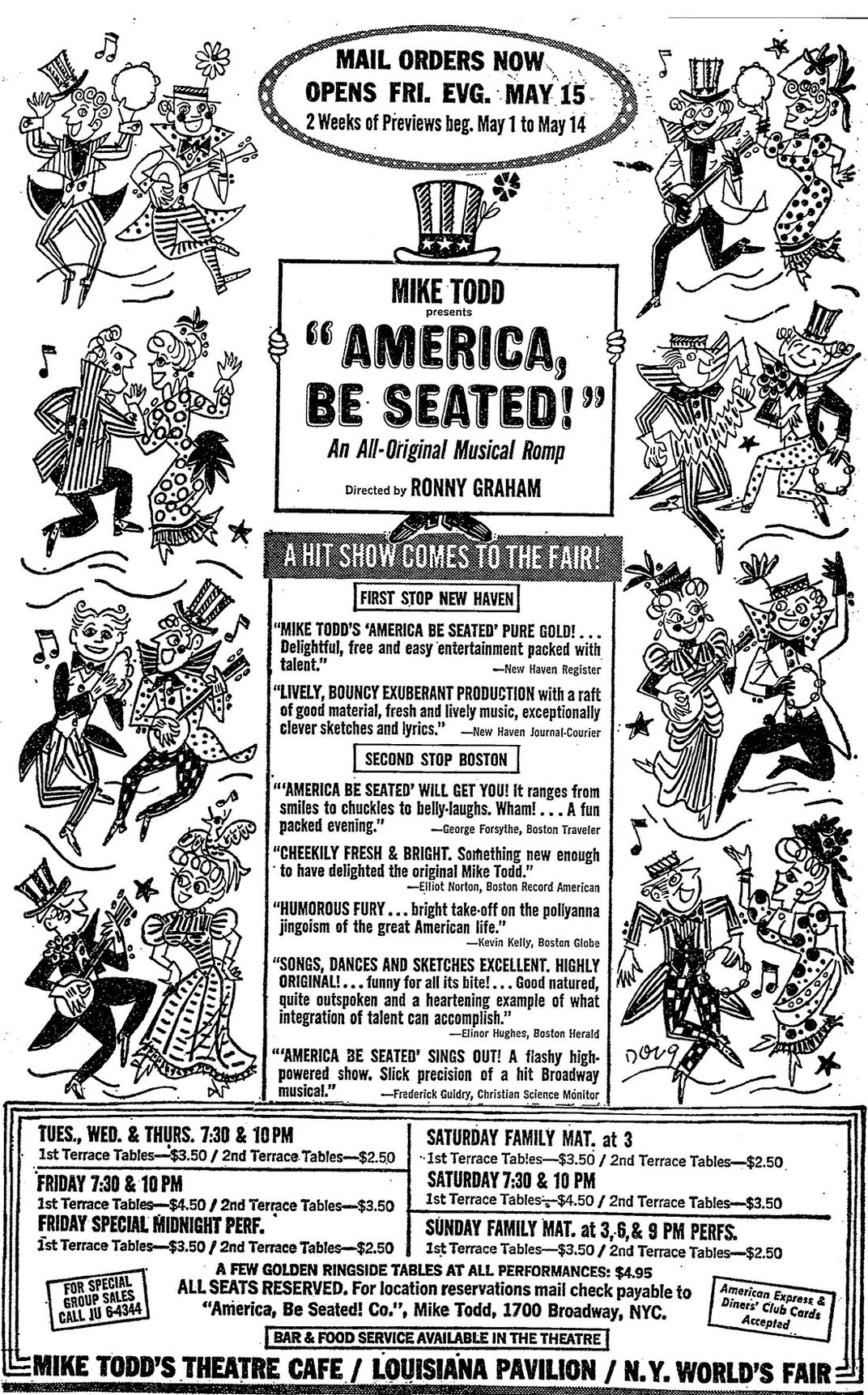

Two weeks after opening day of the 1964 New York World’s Fair, a minstrel show like no other debuted on the Flushing Meadows fairgrounds. America, Be Seated!, the Louisiana Pavilion’s self-styled “modern minstrel show,” ditched the blackface and featured an integrated cast of white and black actors singing and dancing in harmony. According to a World’s Fair press release, the “all-stops-out slapstick pageant of American history” would combine the “happy flavor of minstrel shows…with original music and modern comedy skits.”

The concept sounds like a contradiction in terms: Minstrelsy, a relic of 19th-century theater, disappeared from the American stage in the early 1900s, and its defining component, blackface, was rooted in racism. Blackface minstrel shows originated in the 1830s as a popular form of musical entertainment: white actors, made up with burnt cork or greasepaint, performed sentimental songs and comedy bits with exaggerated mannerisms based on black stereotypes. This genre went into decline after the Civil War as vaudeville took over the nation’s theaters, but blackface made the leap from stage to screen, appearing in films such as The Jazz Singer (1920) and Swing Time (1936), and to radio, heard in the long-running serial “Amos ‘n’ Andy.” But the “updated” minstrel show at the 1964 World’s Fair defied the bigoted origins of the genre to become, ironically, the event’s most progressive attraction.

Historically, world’s fairs were all about progress. These international expositions, staged in cities around the globe from the 1850s to the 1960s, unveiled dazzling inventions, such as the sewing machine (1855) and the elevated train (1893), along with utopian visions of the future, such as General Motors’ “Futurama” at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, which depicted a network of expressways connecting the United States. That year’s World’s Fair, also in Flushing Meadows, Queens, is regarded as one of the most influential of the 20th century, renowned for its streamlined art deco style and technological innovations.

The 1964-65 World’s Fair, on the other hand, was a study in corporate excess. Boasting an 80-foot-tall tire Ferris wheel (sponsored by U.S. Rubber), Disney-produced animatronics (including the debut of “It’s a Small World”), and a tasteless display of Michelangelo’s Pieta (set in a niche with flickering blue lights, behind bulletproof glass, accessible only by moving walkway), the Fair was not nearly as rarefied as its theme of “Peace Through Understanding” let on. The New York Times’ Ada Louise Huxtable called the Fair’s architecture kitschy and “grotesque.” “There are few new ideas here,” she wrote. “At a time when the possibilities for genuine innovations have never been greater, there is little real imagination…” Historian Robert Rydell has described the 1964 Fair as a “large, rambling, unfocused exposition” that ended the era of American world’s fairs.

Much of the blame has been laid on Robert Moses, president of the World’s Fair and mid-20th-century “master builder” of New York City. Moses pledged that the event would cater to “middle roaders,” meaning the ordinary middle-class folks “in slacks and…in their best bibs and tuckers” who came in search of a wholesome good time. The Fair, he vowed, would have no point of view on art or culture or politics. But his incessant diatribes against “avant garde critics and leftwing commentators” amounted to a platform of lily-white conservatism, conforming to his own septuagenarian tastes. In 1962, the Urban League accused the World’s Fair Corporation of racially discriminatory hiring practices, forcing Moses, who dismissed the charges as “nonsense,” to begrudgingly adopt an equal-employment policy. Moses was never a friend to minorities—his slum clearance policies displaced thousands of low-income New Yorkers, overwhelmingly black and Hispanic—and the picture he wanted to present at the Fair was one of blissful ignorance rather than integration. It was about the “warmth, humanity and happiness visible these summer days on Flushing Meadow,” he wrote in October 1964. “That’s the Fair. That’s New York after three hundred years. That’s America.”

Trite as it was, America, Be Seated! challenged that credo of complacency. The musical was the brainchild of Mike Todd, Jr. (son of film producer Mike Todd), who saw it as a bona fide theatrical work rather than a carnival amusement. Todd Jr. predicted that the show would ride its World’s Fair success to productions elsewhere in the country. “It could go anywhere,” he told the New York Times.

Much to his chagrin, the show went nowhere: it closed after two days with a paltry $300 in receipts. But a May 3, 1964, cast performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show”—the only known recorded performance of the musical—offers clues to what America, Be Seated! looked like and why it didn’t catch on. (An archival copy of the episode is available for viewing at the Paley Center for Media in New York City. We were unable to locate any images of the show.)

The cast appeared on “Ed Sullivan” to promote the musical’s World’s Fair debut in grand Louisiana showboat style: ladies in ruffled bodices and flouncy A-line skirts; men in ruffled tailcoats, plaid lapels, and two-tone shoes; and everyone in straw porkpie hats. Four of the show’s fifteen performers were black, and three of these were featured soloists as well as stars in their own right—Lola Falana and Mae Barnes on the swinging “That’s How a Woman Gets Her Man,” and Louis Gossett, Jr. on the man’s response, “Don’t Let a Woman Get You, Man.” One song, “Gotta Sing the Way I Feel Today,” was unabashedly mawkish, with lyrics like “Share this wonderful feeling in the air.” But the title number addressed what would have been on every viewer’s mind: race. Between verses, the interlocutor (Ronny Graham) downplayed the issue:

Now, somebody said our minstrel show should not be done for sport

That we should have a message of significant import

And so we have a message, a most essential one

Please listen very carefully

Our message is…have fun!

The song’s chorus, however—“America, be seated, here’s a modern minstrel show”—repeatedly brought race to the fore.

To invoke minstrelsy was to invoke race and, in 1964, racial strife. Even Flushing Meadows had a part to play in the battle for civil rights: on the Fair’s opening day, April 22, members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) disrupted subway traffic to the fairgrounds and picketed in front of park and pavilion entrances. President Lyndon B. Johnson was on hand to deliver the opening address, and during his speech, protestors shouted “Freedom Now” and “Jim Crow Must Go!” These demonstrations took advantage of World’s Fair media coverage to draw attention to the cause. They were directed not at the Fair but at the American public.

“For every new car that is shown at the World’s Fair, we will submit a cattle prod,” said CORE leader James Farmer. “For every piece of bright chrome that is on display, we will show the charred remains of an Alabama church. And for the grand and great steel Unisphere [the centerpiece of the Fair], we’ll submit our bodies from all over the country as witnesses against the Northern ghetto and Southern brutality.” When Farmer blocked the door to the New York City pavilion, he called it a “‘symbolic act,’ in the same way…that Negroes have been blocked from good jobs, houses and schools in the city.” The New York Times reported that “most of the opening-day crowd seemed to pay little attention,” however, and those that did responded with obscenities and comments like “Ship ’em back to Africa” and “Get the gas ovens ready.”

Of the 750 demonstrators, less than half were arrested, mostly on charges of disorderly conduct that were later dropped, and seven people sustained minor injuries. Both sides were eager to avoid the violence that continued to rage in the South. Less than eight months prior, four black girls were killed in the bombing of a Birmingham church. In January 1964, Louis Allen, a black Mississippi man who had witnessed the murder of a voting-rights activist, was shot to death in his driveway. In March, race riots in Jacksonville, Florida, claimed the life of a 35-year-old black mother, Johnnie Mae Chappell. And after the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee announced plans for its “Freedom Summer,” the Ku Klux Klan began to mobilize in Mississippi, burning crosses throughout the state on April 24. The specter of racial unrest would have loomed large in fairgoers’ minds when they heard the term “integrated” and saw blacks and whites together on stage in America, Be Seated!

Judging by reviews of the musical’s previews in Boston and New Haven, Connecticut, America, Be Seated! attempted to confront the issue of race head-on. Critical response was mixed, but all of the reviewers commented on the politics of the production. Frederick Guidry of the Christian Science Monitor called the show a “lighthearted call for people all over the United States to find refuge from racial tension in a relaxed acceptance of the American ideal of equality.” These earlier performances contained segments too edgy for “Ed Sullivan.”

In the preview Guidry saw, the opening number contained an overt allusion to the civil rights movement—“We haven’t a lot of time to read / But can we picket, yes indeed!”—which was noticeably absent from the “Ed Sullivan” version. “The struggle for full equality,” Guidry wrote, “is never very far from a lyric or a joke.” One comedy bit saw a white director asking a black actor to play to slave stereotype; the actor responded, “I’m chairman of the local chapter of CORE, and you’re going to call me Rastus?”

The show’s boldest jokes, however, came from black comedian Timmie Rogers. According to Boston Globe critic Kevin Kelly, Rogers “razz[ed] his own race with a humorous fury that might even bring a smile to the NAACP. Rogers, for example, explained that Negroes have a new cosmetic to keep up with the white man’s desire to be tanned. It’s called Clorox.” The comedian also referred to a new white youth organization called SPONGE, or the Society for the Prevention of Negroes Getting Everything.

Remarkably, the musical received support from the NAACP. The organization, understandably turned off by the minstrel show label, was critical of the production at first, but after seeing a Boston preview NAACP officials reversed their stance, praising the revue as an “asset for integration.” William H. Booth, president of the Jamaica, Queens, NAACP branch said: “I have no serious objections. There is nothing in this show detrimental to or ridiculing Negroes. In fact, it is a satire on the old-style minstrel show.”

The organization expressed concerns over Timmie Rogers’ jokes about Clorox skin bleach and cannibalism in the Congo, but the comedian agreed to cut them. Boston NAACP president Kenneth Guscott stated that “while the NAACP is flatly against minstrel shows, this one is an integrated production in the true sense that it shows how Negroes feel about discriminatory stereotypes.” Another NAACP official called America, Be Seated! a “spoof on Negro stereotypes.”

The critical consensus was that despite its minstrel show marketing—and Variety’s optimistic prediction that it could be “the forerunner of a revival of minstrelsy”—America, Be Seated! actually hewed closer to the vaudeville tradition. Without blackface, it only had the music and three-part structure of traditional minstrelsy. In the end, that miscategorization may have spelled the show’s rapid doom. Variety reported that the “‘minstrel’ connotation” proved to be “b.o. [box office] poison” at the New Haven premiere and that Mike Todd subsequently dropped it from the show’s publicity. But the lyrics of the opening number remained unchanged for the “Ed Sullivan” appearance, which in any case “proved no b.o. tonic.”

Tepid turnout for the Fair as a whole didn’t help the musical’s prospects. The 1964-65 Fair drew a total of 52 million visitors in two seasons—well short of its projected 70 million—and closed with $30 million in debt.

Mike Todd Jr., whose chief claim to fame (aside from his parentage) was a movie theater gimmick called “Smell-o-Vision,” blamed philistines for the musical’s failure. He told the New York Amsterdam News that “presenting it at the Louisiana Pavilion was like trying to bring legitimate theatre into a night club. It couldn’t compete with the drinks.” In an interview with the Boston Globe, he complained about the Fair’s consumerist atmosphere. “All I could see was kids with hats on,” he said. “World Fair hats…the kind with a feather in it that always gets lost on the way home. That’s what the people were buying. Hats, not shows.” As Timmie Rogers put it, they “never had a chance.”

Fifty years later, a handful of reviews and a set on “Ed Sullivan” are all we have to judge the merits of America, Be Seated! It was a corny show, to be sure, but not much cornier than anything else at the World’s Fair, which promised good, old-fashioned, apolitical fun. Even though Todd Jr. inflated the musical’s long-term prospects, there’s no doubt that America, Be Seated! offered something exceptional: a reappropriation of a taboo style. It meant well. But for whatever reason, fairgoers weren’t interested in seeing a “modern minstrel show.”