Meet the Madam on the Mall

Mary Ann Hall ran a successful brothel in D.C. for years, but it took a 1997 dig to tell the whole story

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/b2/beb20edf-da7e-4a28-af74-72aace4e4930/mall2.jpg)

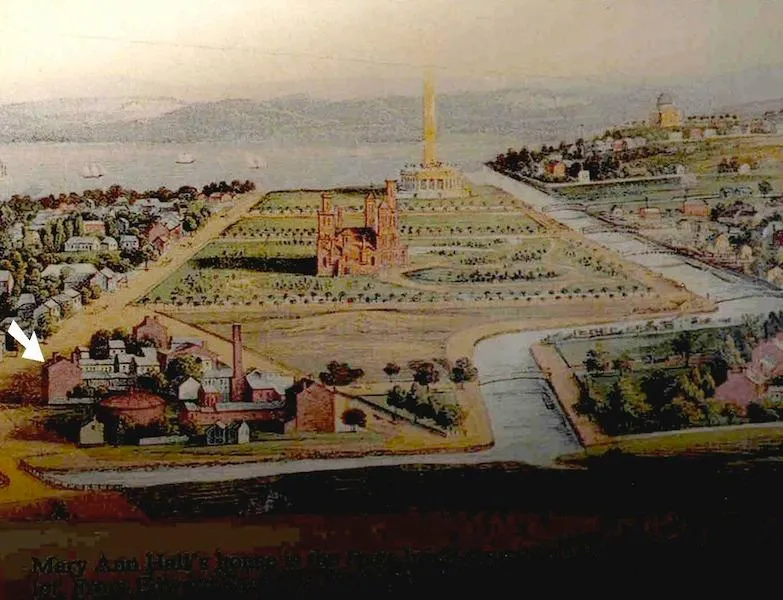

Laughter, hoots and hollers would regularly pour out of the large multiple-story brick house in Washington, D.C.’s southwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. Mere steps from Congress, this mid-19th century establishment was eloquently furnished, flowing with champagne, and altogether grand, both in the size of the house and who frequented it. For over 40 years, spanning the terms of 14 presidents, this house stood, delighting and satisfying visitors. One woman, Mary Ann Hall, oversaw nearly all of it. More than a century after her death, she would be given a nickname - the Madam on the Mall - for this house of ill repute on Maryland Avenue was the classiest and most famous brothel in all of Washington, D.C.

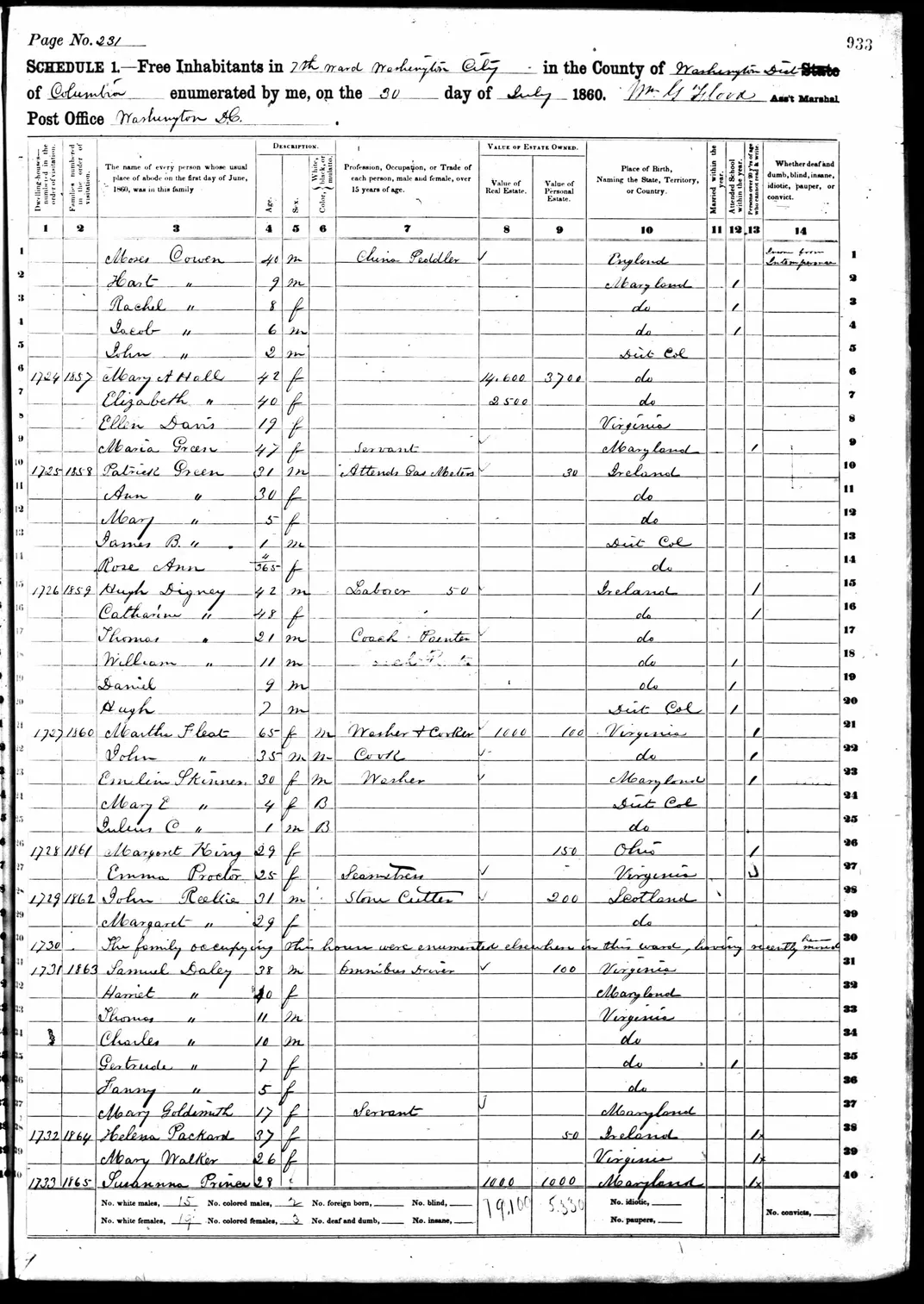

Very little is known about Mary Ann Hall’s private life. The exact date of her birth cannot be confirmed, though sources point to her being born between 1815 and 1818 (even official federal government censuses vary in year). We do know she was born in Washington, one of nine children. At some point, Mary became a prostitute, earning enough money by her early 20s to buy a lot in the swampy and unkempt area along the canal and located on what is now known as the National Mall. Known as Reservation C, this section of the city had been broken up into lots for private sale in 1820. Hall’s purchase was official in August 1839, and she swiftly erected a three- or four-story brick house on the lot. The 1840 Census indicates that Hall’s business (though, her last name is spelled “Haw” on the census, presumably in error) was off and running early that year, with five white females under the age of 30 and one free “colored” female between the ages of 24 and 36 all living under this one roof. Ten years later, according to the 1850 census, Mary’s younger sister Elizabeth would join them, as well as a 50-year-old “Mulatto” woman named Judy Fleet. Interestingly, their occupations were all listed in the 1850 census as “substitute.”

By 1840, over 23,000 people lived in Washington. That would number would nearly double by 1850 and, on the eve of the Civil War, the population within Washington’s boundaries had reached beyond 60,000.

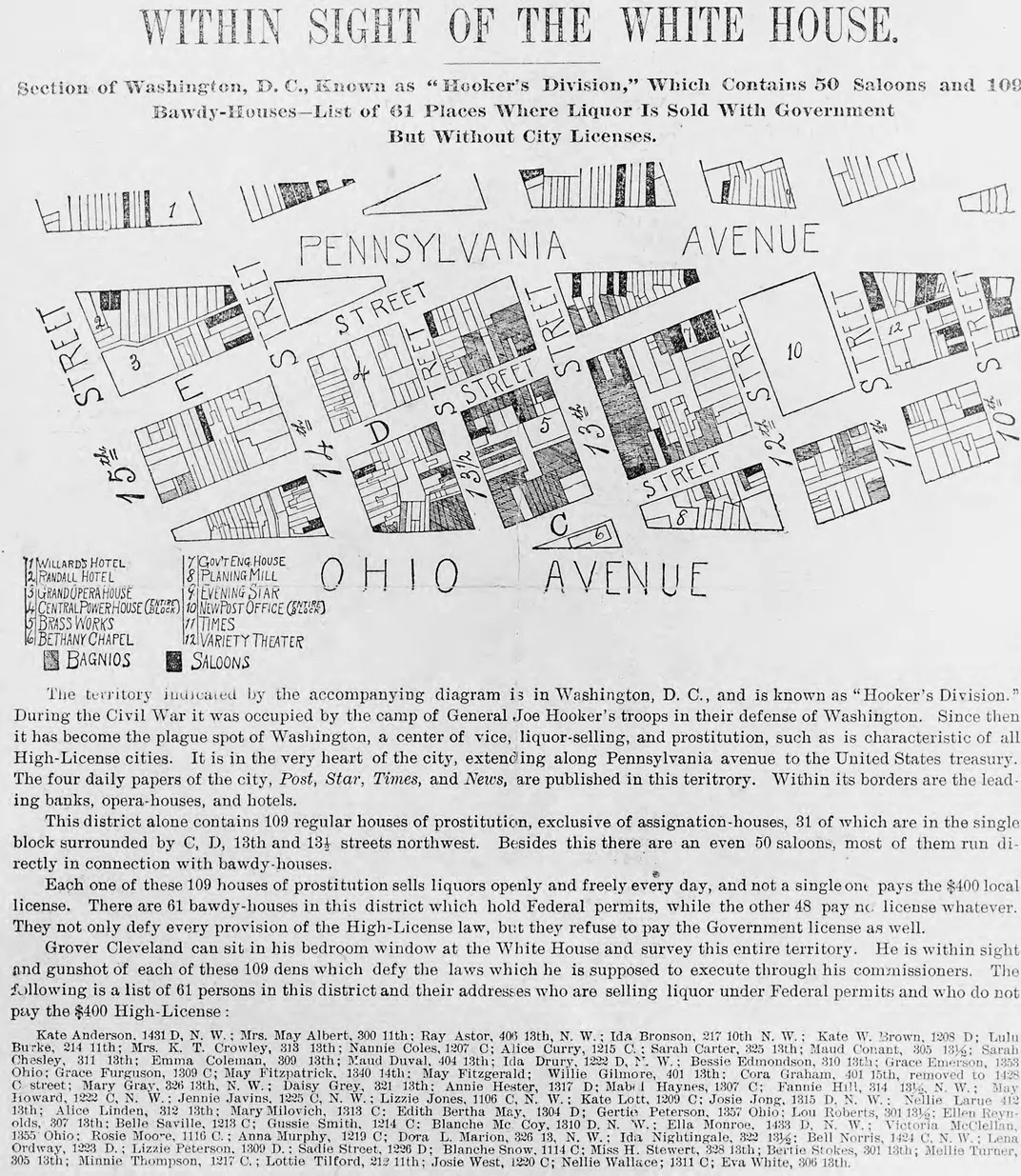

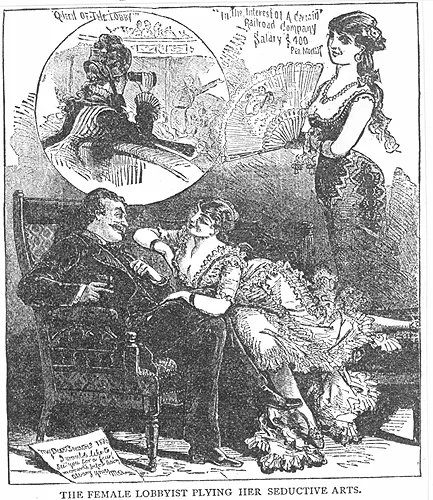

With this population boom, came overcrowding, slums and proliferation of sin. Saloons, gambling houses, opium dens and brothels, or, to borrow the term used at the time, “bawdy houses” dotted the D.C. landscape. Reservation C, with its prone-to-overflowing canal and cramped working class homes had its fair share of vice and, as described in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1997 archaeological report of the area, it “never became a fashionable neighborhood.” Yet, with these squalid conditions, Mary Ann Hall was able to fashion a high-quality brothel that catered to a rather illustrious clientele.

Right on the eve of the Civil War, Mary’s brothel was thriving. The 1860 census reveals that the value of her real estate and personal estate combined was a little over $18,000 (a touch under $500,000 in today’s dollars, according to some calcuations.) There is no (at least, surviving) list or registry of who came and went, but evidence points to most guests being of wealth and influence. Even though the 1860 census only counts four women to actually be living within, sources indicate that up to 17 worked out of the house. Historical accounts state that the house had up to 25 rooms, many decorated with large oil paintings, red plush parlor furniture, expensive European carpets, and items fashioned from silver plate. Guests and residents alike ate off ironside and porcelain dishware, considered fashionable in the day. Meals consisted of high and mid-priced cuts of beef, pork and goat, plus other meats like wild birds, fish and turtle. Fruits and nuts, including coconut and brazil nuts, considered quite exotic in 1860, were served. So was the ever-flowing expensive French champagne.

An order given to the Metropolitan Police of Washington in 1862 stated, that officers should arrest all “public prostitutes and all persons who lead a lewd and lascivious life.” More often than not, detainments of prostitutes would be tied to another crime, including fighting, disorderly conduct or larceny. As going back through police blotters from the era reveals, “keeping a bawdy house” could get one thrown into jail for months and forced to pay “costs and fines.”

Mary had a run-in with the law herself when police raided the brothel on January 18, 1864. She was indicted in the D.C. Circuit Court with “keeping a bawdy house and disorderly conduct.” Coverage of the incident in that day’s Washington Evening Star (the city’s newspaper of record) described Mary as “keeper of the ‘old and well established’ ranch on Maryland Ave. She came to the police station “in a suit of virtuous black... in company with her sister Lizzie Hall.”

When the trial began a month later, she hired attorney Joseph H. Bradley Sr. to mount a defense. Two-and-a-half years later, Bradley would defend John Surratt on charges of involvement in the assassination of President Lincoln. In the press coverage of the trial, reporters indicate that a police officer witness described seeing “hacks (horse-drawn equivalents of today’s taxi cabs) frequently in front of the house, from which he had seen mostly males get out.” Additionally, the “front door had a ball and chain on it, so that it could be opened about six inches that persons might be seen before being admitted.” Witnesses (mostly police officers) go on to describe their “visits” over the last few years, often finding up to ten women, other police, and “officers of the Army and Navy” in the premises, with everyone acting as if “a wedding party was going on - champagne was being handed around.”

Hall would eventually be found guilty of “keeping a bawdy house” and fined a hefty sum of $2,000 (today, about $30,000). This wasn’t the last time Mary and her house would be in the newspaper. On August 19 of that same year, as described in the Evening Star, a fight broke out at the house between “Miss Lizzie Pearce, a buxom English lasse, and Miss Lilly Ellis.” Apparently, they “had some words, which resulted in the English girl putting in two or three well directed blows as the deep mourning around Lizzie’s left eye shows.”

Beyond the newspaper reports, much of what we know about Mary Ann Hall’s enterprise comes from the 1997 dig and the subsequent report, which gave her the nickname “Madam on the Mall.”

Eight years prior, President George H.W. Bush signed the National Museum of American Indian Act and set in motion the process that ended with the completion of a new museum on the National Mall in 2004. But before construction could begin, investigators surveying the site revealed that building foundations and artifacts lay beneath the sod, buried and untouched for more than a century. Old maps and real estate records confirmed that this was site of Mary Ann Hall’s brothel. Archaeologists immediately went to work.

The dig focused not only on the lot on which Hall had her establishment, but the lot adjacent as well - where the house threw its trash. This is where archaeologists found hundreds of champagne corks and broken bottles, shards of expensive porcelain, bones from high-priced cuts of meat, seeds from fruits, oyster shells and numerous women’s grooming/fashion items (like bobby pins, buttons, shoe horns and corset fasteners). It was a treasure trove of trash that continued to tell the story of Mary Ann Hall.

Amy Ballard is a senior historic preservation specialist at the Smithsonian and helped lead the dig back in 1997. She explained over email that, while they didn’t know exactly what they were going to find, “There were suspicions. The team did much archival research prior to any shovel tests in the first phase. The record books showed that several women lived in one house, which was a bit odd in itself.” It was the artifacts that truly pointed towards the scandalous nature of the property.

Further evidence reaffirmed that this wasn’t just any old brothel either, “One can only imagine some of the clientele since the brothel was in such close proximity to Capitol Hill! She was not catering to the poor soldier - they would have gone to poorer brothels in the city and even Alexandria,” wrote Ballard. The historical significance of “Mrs. Hall” herself should not be forgotten either, emphasized Ballard, “she was one of the very first female entrepreneurs and landowner in Washington and perhaps the United States. And had one of the first integrated businesses as well.” Today, many of these artifacts are stored at the Historical Society of Washington D.C. and can be viewed by the curious with an appointment.

After the war, Mary’s brothel continued to thrive, but as she approached her late 50s, she began to move away from the business. As the years rolled on, She spent more time on her farm in nearby Alexandria county, leaving the day-to-day operations to her sister. Reservation C was becoming more crowded by the day, with working class families of all cultures - German, Irish, English, and African-American (though they often lived in houses facing Maine Ave and not Maryland Ave) - moving in. Small houses were built into alleys in attempt to alleviate the post-war housing shortage in the city. This turned a not particularly fashionable neighborhood into one that was known for its “filth and squalor.”

In June of 1883, Mary Ann officially moved on from the brothel business and rented out part of her property to the “Washington Dispensary for Women and Children,” which was primarily a women’s health clinic. According to the archaeological report, it was “run by two female doctors, the clinic was funded with private donations and money from the D.C. Commissioner's appropriation for the relief of the poor.”

When Hall died from a cerebral hemorrhage, the Evening Star rang her obituary, which read, “Departed this life 2 a.m. Friday January 29, 1886, Mary A. Hall, long resident of Washington. With integrity unquestioned a heart ever open to appeals of distress, a charity that was boundless, she is gone; but her memory will be kept green by many who knew her sterling worth. Funeral strictly private.”

Her two estates (one in Alexandria, Virginia), plus bonds and securities were valued at over $87,000 dollars at the time of her death, the equivalent of more than $2 million today. Upon her death, the family squabbled over her fortune, with her ever-present sister Lizzie fighting against their two brothers. Eventually, her wealth was disseminated among the family.

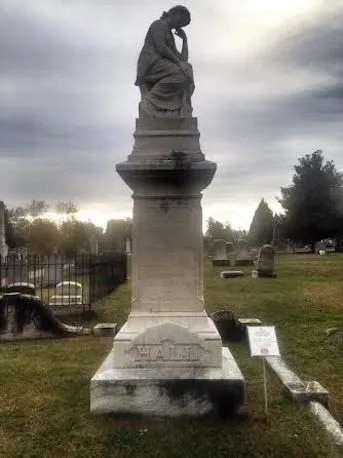

Today, Mary, along with her sister Lizzie and their mother, can be found in Washington’s Congressional Cemetery with an impressive monument that towers over their neighbors. The inscription reads, “Truth was her motto; her creed charity for all. Dawn is coming.” And for over 40 years, at the foot of the Capitol, Mary Ann Hall welcomed all to her brothel for a riotous good time. Provided you had a fair amount of money to spend.

On Saturday Feb 21, Atlas Obscura and the Historical Society of Washington D.C. will be exploring the artifacts and the story of the "Madam on the Mall" at this exclusive Obscura Society DC event.