Weeks before Halloween, I found myself pacing the aisles of a costume store. I had volunteered to help with my child’s classroom party, and though I had a witch hat at home I wanted an outfit that would be more commanding. I decided on a horned Viking helmet with long blond braids glued on.

A few months later, I happened to come across the origins of this costume. It was first worn by Brünnhilde, the protagonist of Richard Wagner’s epic opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen. For the opera’s 1876 production, Wagner’s costume designer outfitted the characters in helmets, both horned and winged. Brünnhilde went on to become opera’s most recognizable figure: a busty woman in braids and helmet, hefting a shield and spear.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/75/9175873e-98d5-413c-ade7-bef26a93fc61/janfeb2022_h03_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

In Wagner’s story, Brünnhilde is a Valkyrie, tasked with carrying dead warriors off to the heroes’ paradise of Valhalla. At the end of the 15-hour opera cycle, she throws herself into her lover’s funeral pyre. First, though, she belts out a poignant aria, giving rise to the expression, “It ain’t over till the fat lady sings.” Her character became yet another way to casually ridicule women’s bodies and their stories.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/5f/c05f8cdf-5be6-4960-9f53-474a0d4e6e55/janfeb2022_h17_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

Because while millions are familiar with the operatic Brünnhilde, few today recall that she shares a name with an actual Queen Brunhild, who ruled some 1,400 years ago. The Valkyrie’s fictional story is an amalgam of the real lives of Brunhild and her sister-in-law and rival, Queen Fredegund, grafted onto Norse legends.

The ghosts of these two Frankish queens are everywhere. During their lifetimes, they grabbed power and hung on to it; they convinced warriors, landowners and farmers to support them, and enemies to back down. But as with so many women before them, history blotted out their successes and their biographies. When chroniclers and historians did make note of them, Brunhild and Fredegund were dismissed as minor queens of a minor era.

And yet the empire these two queens shared encompassed modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western and southern Germany, and swaths of Switzerland. And they ruled during a critical period in Western history. Janus-like, they looked back toward the rule of both the Romans and tribal barbarian warlords, while also looking forward to a new era of nation-states.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/08/be0825c1-969e-47ab-b6ce-399c2e1e11b9/janfeb2022_h01_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

Both ruled longer than almost every king and Roman emperor who had preceded them. Fredegund was queen for 29 years, and regent for 12 of those years, and Brunhild was queen for 46 years, regent for 17 of them. And these queens did much more than simply hang on to their thrones. They collaborated with foreign rulers, engaged in public works programs and expanded their kingdoms’ territories.

They did all this while shouldering the extra burdens of queenship. Both were outsiders, marrying into the Merovingian family, a Frankish dynasty that barred women from inheriting the throne. Unable to claim power in their own names, they could only rule on behalf of a male relative. Their male relatives were poisoned and stabbed at alarmingly high rates. A queen had to dodge assassins, and employ some of her own, while combating the open misogyny of her advisers and nobles—the early medieval equivalent of doing it all backwards and in heels.

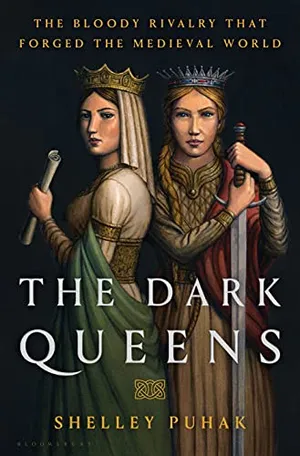

The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry That Forged the Medieval World

The remarkable, little-known story of two trailblazing women in the Early Middle Ages who wielded immense power, only to be vilified for daring to rule

He did not address his subjects on the matter of Galswintha’s demise. There were no searches for her assailants.

I didn’t know these queens’ names when I stood in that costume store aisle. But at some level, I knew these queens. You know them, too, even if your history books never got around to mentioning them. I call them the Dark Queens, not only because the period of their rule falls neatly into the so-called Dark Ages, but also because they have survived in the shadows, for more than a millennium.

In the spring of 567, the map of the known world looked like a pair of lungs turned on their side—just two lobes of land, north and south, with the Mediterranean Sea between them. Princess Brunhild came from the very tip of the left lung, in Spain. She had just traveled more than one thousand miles, across the snowcapped Pyrenees, through the sunny vineyards of Narbonne, and then up into the land of the Franks. Throughout the whole journey, she had been trailed by wagons piled high with gold and silver coins and ingots, bejeweled goblets, bowls and scepters, furs and silks.

Now she was led into what the Franks called their “Golden Court” to meet her new subjects. The hall was bedecked with banners and standards; there were thick rugs on the floors and embroidered tapestries on the walls. But if the princess had peeked behind one of these tapestries, she would have noticed the fresh plaster. The ambitiously named Golden Court was still being patched together, just like the city itself.

King Sigibert’s kingdom, called Austrasia, was centered along the Rhine River. At its northernmost tip were the coastal lowlands of the North Sea, and its southernmost point was Basel in the foothills of the Jura Mountains. Along its eastern border were cities like Cologne and Worms, and along its western border were the rolling hills and vineyards of the Champagne region. Sigibert also owned lands in the Auvergne and ruled over the Mediterranean ports of Nice and Fréjus, which welcomed ships, and people, from all over the known world. In his cities one could find Jews, Christian Goths and pagan Alemanni; Greek and Egyptian doctors; even Syrian merchants.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a1/57/a157635d-4fbb-403c-a3dc-6ea0f53a08a8/janfeb2022_h11_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

Yet the size of Sigibert’s kingdom, while respectable enough, was not what had secured this marriage. Rather, it was the size of his ambitions. He had negotiated for months for Brunhild’s hand, and his subjects must have felt hopeful, triumphant even, now that he had secured such a prestigious mate.

Beautiful (pulchra), they called her, and lovely to look at (venusta aspectu) with a good figure (elegans corpore). There is no way for us to judge for ourselves. She appears unnaturally tall and pale in illuminated manuscripts from later in the medieval period; voluptuous and glowing in Renaissance portraits; pensive and windswept in Romantic-era prints.

After her death—the statues pulled down, the mosaics obliterated, the manuscripts burned—no contemporary images of her would survive. Still, those present on her wedding day claimed she was attractive. There are no mentions of her being unusually short or tall, so one can assume she stood close to the average height for a woman of the period, 5 feet 4 inches tall. She was around 18 years old, and arrayed in the finest embroidered silks her world could muster, with her long hair loose about her shoulders and wreathed in flowers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e7/e8/e7e8235a-3562-4f11-a541-6c10dbba0b24/3_maps.jpg)

The only contemporary image of her bridegroom that survives is that of his profile on a coin. Sculptures made many centuries later portray him as a tall, lean young man with long blond hair falling in waves to his chin. His features are well-proportioned and his expression is kind; his shoulders are broad and his cheekbones are high. He appears to be a veritable medieval heartthrob.

While these are probably not close likenesses, they have some basis in fact. King Sigibert wore his hair long and it is likely that he was a blond or redhead, like many in his family. Sigibert’s name meant “Magnificent Victory” and he was a renowned warrior, so he would have been fit and muscular and, at 32, at the height of his physical powers. They must have made a striking couple as they stood side by side, the sumptuously attired and immaculately groomed princess, the strapping king.

Across the border, in the neighboring kingdom of Neustria, another palace overlooked the Aisne River. Here, the news of Sigibert and Brunhild’s marriage was met with great interest and alarm by Sigibert’s youngest brother, King Chilperic.

If the sculptures are to be believed, Chilperic looked very similar to Sigibert, although he had curlier hair. But if they shared certain features, they did not share any brotherly affection. Sigibert and Chilperic did share 300 miles of border, a border that Chilperic was constantly testing. Chilperic, frustrated at having inherited the smallest portion of their father’s lands, had spent the past few years trying to invade his older brother’s kingdom and, in fact, had just launched a new attempt.

Brunhild undertook repairs to the old Roman roads throughout both kingdoms with an eye for making trade easier.

He was not surprised that Sigibert had married. Chilperic himself had started trying to beget heirs when he was still in his teens—why had his brother waited so long? By choosing a foreign princess for his bride, Sigibert was declaring his dynastic ambitions, and Chilperic was furious to be outmaneuvered.

Chilperic’s first wife had been exiled many years before, parked in a convent in Rouen. As Chilperic cast about for an appropriately valuable princess, one who might upstage Brunhild, he could think of no better candidate than Brunhild’s own elder sister, Galswintha. A year earlier, the princesses’ father, King Athanagild, would have laughed at Chilperic’s proposal. He had no sons. Why would he waste his first-born daughter on the Frankish king with the least territory?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/91/1f91fc88-c9ff-48c4-91ff-4e765ce0de7e/janfeb2022_h04_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

But Chilperic made a startling offer. Tradition held that a bride be given a morgengabe, or morning gift, after the couple consummated their marriage. The more prestigious the bride, the more extravagant the morgengabe. Sigibert, for example, seems to have given Brunhild a lavish estate in what is now southern France. Chilperic, though, was willing to offer Galswintha a morgengabe that comprised the entire southern third of his kingdom.

This sort of gift was unprecedented in any kingdom or empire. Galswintha would control five wealthy cities: Bordeaux, Limoges, Cahors, Lescar and Cieutat. All would be hers, their cobblestones and ramparts, their citizens and soldiers, their luxurious estates and plentiful game, and their considerable tax revenues.

Just a year into their marriage, Galswintha caught Chilperic in bed with his favorite slave girl, Fredegund. The queen was outraged and wanted to return home, even if it meant leaving her enormous dowry behind. One morning, soon thereafter, the palace woke to a horrible scene. Galswintha had been found dead in her bed, strangled in her sleep.

Three days later, arrayed in the brightly dyed linens and jewels of her predecessor, Fredegund stood at the altar, smiling up at Chilperic.

At Frankish wedding feasts, the tables were loaded down with food we would have no trouble recognizing today: loaves of white bread, beef slathered in brown gravy, carrots and turnips sprinkled with salt and pepper. The Franks’ love of bacon was renowned, too, as were their sweet tooths, so much so that the kings themselves owned many beehives. Honey sweetened the cakes baked for special occasions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/da/bcdaacb6-ad0c-4da1-b728-39fef29515b8/janfeb2022_h12_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

Even though Fredegund’s wedding was hastily organized, some kind of wedding cake was served. There was even a wedding ring. The one Chilperic slipped on the new queen’s finger would have contained a garnet, transported all the way from a mine in India. The stones were all the rage and prized even above diamonds. The rest of her new jewelry had traveled just as far. The amber beads now knotted around her neck came from the Baltic, and the lapis lazuli inlaid into her earrings from Afghanistan. The jewels flowed in from the east, while the slaves, like Fredegund herself, were shipped from the north in wagon carts, their arms bound by jute rope.

Where, exactly, had she come from, this Fredegund, this strawberry-blond slave queen? Was she left on a doorstep? Sold to satisfy a debt? Or, most likely, captured as a child?

Conquest was the mill wheel of the early medieval world. Nearly everyone had a friend of a friend who went off to battle and came back with enough booty to buy a bigger farm or entice a higher-born wife. Likewise, nearly everyone knew a story about someone who had ended up enslaved, carried off as part of that booty. Those captured in raids were shackled and carted to ships at Mediterranean port cities. Some, though, were taken to the nearest large city and pressed into service of the warlord or king who had won them.

This might explain how Fredegund ended up in the palace, where she managed to catch the eye of Chilperic’s first wife, who promoted her from kitchen maid to royal servant. But throughout her own reign as queen, Fredegund suppressed any discussion of where she came from. It is not clear if her parents were dead or if she just wished them to be. What hold did she have over the king, and what had she made him do?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d4/c8/d4c839fb-91dc-4553-a250-2e89a11b8582/janfeb2022_h09_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

When Fredegund returned home, she did so like a true Frankish warrior—“with much booty and many spoils.”

Because if Chilperic was grieving, he could not have done a worse job of it. He did not once address his subjects on the matter of Galswintha’s untimely demise. There were no searches for her assailants or rewards offered for their capture. No one was ever questioned or punished, not even the guards who had been posted at the door of the royal bedchamber that night.

It was Bishop Gregory of Tours, the leading chronicler of the era, who wrote plainly what everyone else was thinking: “Chilperic ordered Galswintha to be strangled...and found her dead on the bed.” Whether Fredegund urged him on or not, people would always assume that she had done so, cleverly disposing of yet another rival for the king’s affections.

Brunhild and Fredegund were now sisters-in-law. They have long been portrayed as locked in a blood feud originating with Galswintha’s murder, blinded by an intense hatred for each other. Yet it’s more likely that each queen viewed their conflict less as a series of personal vendettas and reprisals than as a political rivalry. Frankish politics was a blood sport, but the violence was generally not personal; a king forged and broke alliances, partnering with a brother he had tried to kill only days before.

After Galswintha’s death, the rights to the lands of her morgengabe passed to Galswintha’s family. The case could be made that Brunhild was her sister’s heir. This became the pretext for an invasion carried out by Sigibert and his eldest brother, Guntram. They would start with the five cities that had made up Galswintha’s morgengabe, but hoped they could use the war as a launching pad to seize their brother’s entire kingdom and divide it between themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/be/a9beb313-8ab2-4ca6-ab5e-85ca3781967e/janfeb2022_h15_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

By 575, the fighting had spread to Chilperic’s capital city of Soissons. Sigibert and Brunhild took up residence in Paris, a possible new capital for their new dynasty. Chilperic was forced to pack up his treasury and flee as his brother rode out to accept an offer of loyalty from the nobles in Chilperic’s northernmost territories. As Sigibert was carried through the admiring throngs, soldiers beat their shields with the flats of their swords and the valley rang with their chant: “Sigibert, King of the Franks! Long live the king!”

While Brunhild was being feted as Queen of Paris, Fredegund found herself queen of a bunker 40 miles away. This was the time to make a last confession. (Two generations earlier, most Franks had converted to the religion we now call Catholicism.) Yet Fredegund called no priest into her chambers. Instead, she summoned two slave boys. Fredegund wanted them to slip into the gathering where the armies were celebrating Sigibert’s victory and assassinate Sigibert. If the boys were successful, they’d have no hope of getting out alive. This was a suicide mission.

It was common during the time for all men to carry a scramasax, a hunting knife with a single-edged 12-inch blade. Because such knives were ubiquitous, the boys could carry them openly on their belts and still appear unarmed. Fredegund handed the boys a small glass vial—of poison. While there were many poisons in the Merovingian arsenal, there were only two that could kill on contact: wolfsbane and snake venom. But both lost potency fairly quickly and needed to be applied to the weapon right before an attack. If the account from Gregory of Tours is to be believed, Fredegund had access to both the medical texts of antiquity and the ability to compound dangerous herbs or extract snake venom.

In the morning, the boys likely managed to get into the camp by declaring themselves Neustrian defectors. They smeared their blades with the poison, hung them back on their belts, and caught up with the king, pretending they wanted to discuss something with him. Their youth and apparent lack of armor and weapons set his bodyguards at ease. It wouldn’t have taken much, just the smallest wound. Confused, Sigibert gave a little cry and fell. His guard quickly killed the two boys, but within minutes, Sigibert was dead.

Sigibert’s assassination changed the power dynamic in Francia. Sigibert’s armies fled while Chilperic and Fredegund left their bunker, took control of Paris, and expanded their kingdom’s territory. A grateful Chilperic made his queen one of his most trusted political advisers; soon Fredegund wielded influence over everything from taxation policy to military strategy.

Then in 584, on his way home from a hunting expedition, Chilperic was assassinated. Circumstantial evidence strongly suggests Brunhild was the mastermind of this plot. After many machinations, Fredegund became the regent for her own young son, ruling over Neustria. Soon, the only person standing between the two queens, acting as a buffer, was their brother-in-law, King Guntram.

Guntram ruled over Burgundy, a kingdom on the southern border of both Neustria and Austrasia. He was a widower with no surviving sons, and the queens competed for his favor, hoping he would name one of their sons as his sole heir. Guntram, however, was deeply distrustful of ambitious women and believed that a royal widow should not rule, but retire to a convent. Neither queen was likely to do so. Fredegund’s grip on the regency in Neustria was secure after additional assassinations had cowed her opponents. And Brunhild and her son were addressed as a “couple” and “royal pair,” ruling Austrasia together even after he came of age.

When Guntram finally gave up the ghost on March 28, 592, for once there was no talk of poison. Guntram was, by Merovingian standards, a very old king, just past his 60th birthday. His will was clear about what each of his nephews would inherit. Fredegund and her son were allowed to keep their small kingdom. Queen Brunhild’s son inherited Burgundy, which meant the lands of the “royal pair” now dwarfed and encircled those of Fredegund and her son.

Both queens were now in their late 40s. Middle age is a liminal space for women in any era, but even more so for a Merovingian. According to Frankish law, each person was assigned a monetary value, or wergeld, which their family could demand in compensation if the person was killed. A young woman’s wergeld was generally higher than a man’s. But once the woman was no longer able to bear children, her price usually went down considerably, from 600 solidi to 200.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ac/07/ac07c1ea-fda8-4ba0-a6d4-c9ec761faffb/janfeb2022_h10_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

The economic value of an aging queen was tallied a bit differently. Brunhild’s mother had remarried her second king while in her 40s; he was expecting her to provide not children but political expertise. Freed from the business of pregnancy and birthing, a queen’s value might go up. She had acquired hands-on experience governing, accumulated a list of names in her head—allies and enemies and webs of extended families—and finely honed her sense of timing. She knew how much pressure to apply to which duke, or which duke’s mother, and exactly when.

These were the skills that proved invaluable as Brunhild reassured the Burgundians that their kingdom would not simply be absorbed into Austrasia. To assuage egos and quell future revolts, she allowed many Burgundian officials to keep their positions. But she also created new positions and staffed them with longtime loyalists. King Guntram’s capital had been Chalon-sur-Saone, but Brunhild favored the town of Autun, 30 miles to the northeast. She relocated there to keep an eye on this new second kingdom, leaving her son and daughter-in-law up north in Metz.

Over 200 miles south of Metz, Autun was milder and sunnier, a city that the Emperor Augustus had once declared “the sister and rival of Rome.” It had been famous for its schools of Latin rhetoric well into the fourth century. Once Brunhild was established there, she embarked on a campaign to win over the city’s bishop, Syagrius, a former favorite of Guntram’s. She also sought to centralize power by overhauling the property tax system. She conducted a census and sent out tax investigators to several cities. Many people listed on the rolls had died and their widows and elderly parents had been left to pay their share; by purging the rolls she could “grant relief to the poor and infirm.” Her initiative was much more popular with the common people than it was with the wealthy; nobles resented paying higher taxes on their new lands and villas.

Brunhild also went on a building spree in Autun, aiming to restore it to its former greatness. She erected a church with expensive marble and glittering mosaics, alongside a convent for Benedictine nuns and a hospital for the poor. She undertook repairs to the old Roman roads throughout both kingdoms with an eye for making trade easier.

Peace held until the year after Guntram’s death. Then, in 593, Brunhild approved an attack on Soissons. Fredegund had been ruling from Paris, which meant that the old Neustrian capital had lost some of its importance. But Soissons still retained much of its wealth, and it was right along Brunhild’s border. Brunhild wanted it back.

She sent Duke Wintrio of Champagne, along with some of the nobles from both Austrasia and Burgundy, to invade the villages and towns surrounding Soissons. The countryside was devastated by their attacks and all the crops were burned to the ground.

Fredegund, meanwhile, ordered her stalwart supporter Landeric to marshal what forces he could. And she decided to march out with the men.

Typically, men bonded while serving in the armed forces. Armies had their own cultures, jokes and shared histories. Friendships were formed while marching, pitching camp, deciding strategy; fortunes were made while robbing and pillaging towns. A queen might occasionally be behind enemy lines with her king or while being evacuated from one place to another, but she was decidedly not considered a warrior in her own right.

Fredegund, whether by design or out of desperation, was about to change the script. She and Landeric, and the troops they had been able to gather, marched to Berny-Rivière, once Chilperic’s favorite villa, situated just outside Soissons. There, Fredegund raided one of the treasury storerooms and, like a traditional barbarian king, distributed the valuables among the soldiers. Rather than allowing these riches to fall into the hands of the Austrasians, she had decided to give her men booty in advance of the battle to ensure their loyalty and steel their nerves once they realized how painfully outnumbered they would be.

Fredegund had no hope of beating the opposing forces in outright combat. She decided the battle to defend Soissons should occur at the enemy’s camp 15 miles away in the fields of Droizy; her only chance was a surprise attack. Fredegund followed the dictums of military handbooks such as De re militari, the same way a male Roman field commander might; she chose the battlefield, and she opted for trickery when confronted by a much larger army.

Fredegund ordered her army to march at night, not a typical maneuver. She also counseled her men to disguise themselves. A row of warriors led the march, each carrying a tree branch to camouflage the horsemen behind him. Fredegund had the added inspiration of fastening bells to their horses. Bells were used on horses that were let out to graze; the enemy might hear the ringing and assume it was coming from their own grazing mounts.

There were rumors that Fredegund had used witchcraft to take down her husband’s brother and rival.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/93/fe/93fe2ecb-c6d8-4969-92b4-b1275c8ab01d/janfeb2022_h16_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

The earliest surviving record of the Battle of Droizy is from the eighth-century chronicle Liber Historiae Francorum (The History Book of the Franks), but the usually terse anonymous author became so incredibly specific in this one instance that he seemed to be drawing upon details immortalized by an account from a local monastery or an oral history.

In this telling, a sentry heard the approach of tinkling bells and asked, “Weren’t there fields in those places over there yesterday? Why do we see woods?” Another sentry laughed off this alarm: “But of course you have been drunk, that is how you blotted it out. Do you not hear the bells of our horses grazing next to that forest?” So Brunhild’s forces slept. At daybreak, they found themselves surrounded, and then, slaughtered.

Fredegund’s army saved Soissons and then went on the offensive, riding east and penetrating nearly 40 miles into Austrasia territory, making it all the way to Reims. In retribution for the damage done to the outskirts of Soissons, the chronicle tells us, “she set fire to Champagne and devastated it.” Her armies plundered the villages of the area and when Fredegund returned home, she did so like a true Frankish warrior—“with much booty and many spoils.”

After the queens died, Fredegund’s son, King Chlothar II, took steps to obliterate the memory and legacy of his aunt and even of his own mother. Things only got worse for Brunhild and Fredegund’s reputations after the Carolingian dynasty took over in the eighth century. There were Carolingian women who attempted to rule as regents, too. So historians of the time were tasked with showing that giving women power would lead only to chaos, war and death. Fredegund was recast as a femme fatale, and Brunhild as a murderess lacking all maternal instinct.

With their accomplishments cut from official histories, the queens took root in legends and myths. A “walking forest” strategy like Fredegund’s appeared more than a thousand years later in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Some scholars and folklorists have found iterations of this strategy in the 11th century (used by the opponents of the bishop of Trier), and again at the end of the 12th century (employed by a Danish king to defeat his adversaries). But the Fredegund story predates the earliest of these battles by over three centuries. There are mentions of a walking forest in Celtic myths, which are difficult to date. These myths may have been inspired by Fredegund—or perhaps she was raised in a Celtic community before her enslavement and picked up the strategy from an older pagan tale told to her as a child.

In 1405, the French poet Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies resuscitated the story of Fredegund’s military leadership to defend the female sex: “The valiant queen kept out in front, exhorting the others on to battle with promises and cajoling words.” The poet wrote that Fredegund “was unnaturally cruel for a woman,” but “she ruled over the kingdom of France most wisely.”

During the same period, roads all over France bore the name of Queen Brunhild (or, as she was called in French, Brunehaut). The historian Jean d’Outremeuse wrote about one such road in 1398: The common people, puzzled by how straight it was, concocted a story that Queen Brunhild had been a witch who had magically paved the road in a single night with the help of the devil. These Chaussées de Brunehaut, or Brunhild Highways, were mostly old Roman roads that appear to have been renamed to honor the Frankish queen. It’s possible to ride a bike or take a Sunday drive down a Chaussée Brunehaut even today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/03/48034cb8-8e82-41e2-a1cb-dad4706a54c7/janfeb2022_h13_medievaldarkqueens.jpg)

The queens resurfaced in the 19th century as Romanticism swept Europe. In England there was an obsession with King Arthur, and in France and Germany, with the barbarian tribes that ruled after the fall of Rome. In 1819, people wandered the halls of the Paris Exposition with long hair brushing their shoulders, dressed as Merovingians. A flurry of works featured the queens—including a multitude of books, poems, operas, plays, prints and portraits. The epic poem Nibelungenlied, or The Song of the Nibelungs, written around the year 1200, had been rediscovered and elevated as a national treasure. One of its main plotlines focused on an argument between two royal sisters-in-law that ripped the realm apart. It was this medieval text that served as the inspiration for Der Ring des Nibelungen.

“Who am I if not your will?” Brünnhilde asks her divine father in Wagner’s opera. The question still applies today. Who is this queen? A strange parody of herself, singing songs written by and for men, her ambitions and her humanity hidden underneath a fantastical horned hat.

Today, Brunhild’s grave has no marker. The abbey where she was buried, now in east-central France, was sacked during the French Revolution. Only the lid of her supposed sarcophagus remains. Two pieces of the smooth black marble slab are on display in a small museum alongside vases and statue fragments from antiquity.

Fredegund’s tomb is on display at the majestic Basilica of Saint-Denis in Paris, where it was relocated after the revolution. The queen’s likeness is rendered in stones and enamel set into mortar. In that image, outlined by copper, the former slave holds a scepter and wears a crown. Yet for all the glory of the setting, Fredegund’s complicated legacy is reduced to the inscription “Fredegundia Regina, Uxor Chilperici Régis”—Queen Fredegund, wife of King Chilperic.

Neither monarch is commemorated with the title both demanded during their lifetimes: not wife or mother of kings but “Praecellentissimae et Gloriosissimae Francorum Reginae”—the most excellent and glorious queen of the Franks.

As a girl, I gobbled up biographies of female historical figures: activists, writers and artists, but few political leaders, and even fewer from so deep in the past. I don’t know what it would have meant for me, and for other little girls, to have found Queen Fredegund and Queen Brunhild in the books we read—to discover that even in the darkest and most tumultuous of times, women can, and did, lead.

Adapted from The Dark Queens by Shelley Puhak. Copyright © 2022. Used by permission of Bloomsbury.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(777x76:778x77)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/06/10/061088c8-4812-4de8-bf85-604535b54463/queens_opener.jpg)