How Tennessee Became the Final Battleground in the Fight for Suffrage

One hundred years later, the campaign for the women’s vote has many potent similarities to the politics of today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/51/6551174b-f41e-4302-b477-73c052020e18/52_apaulvictorybanner_womanshour.jpg)

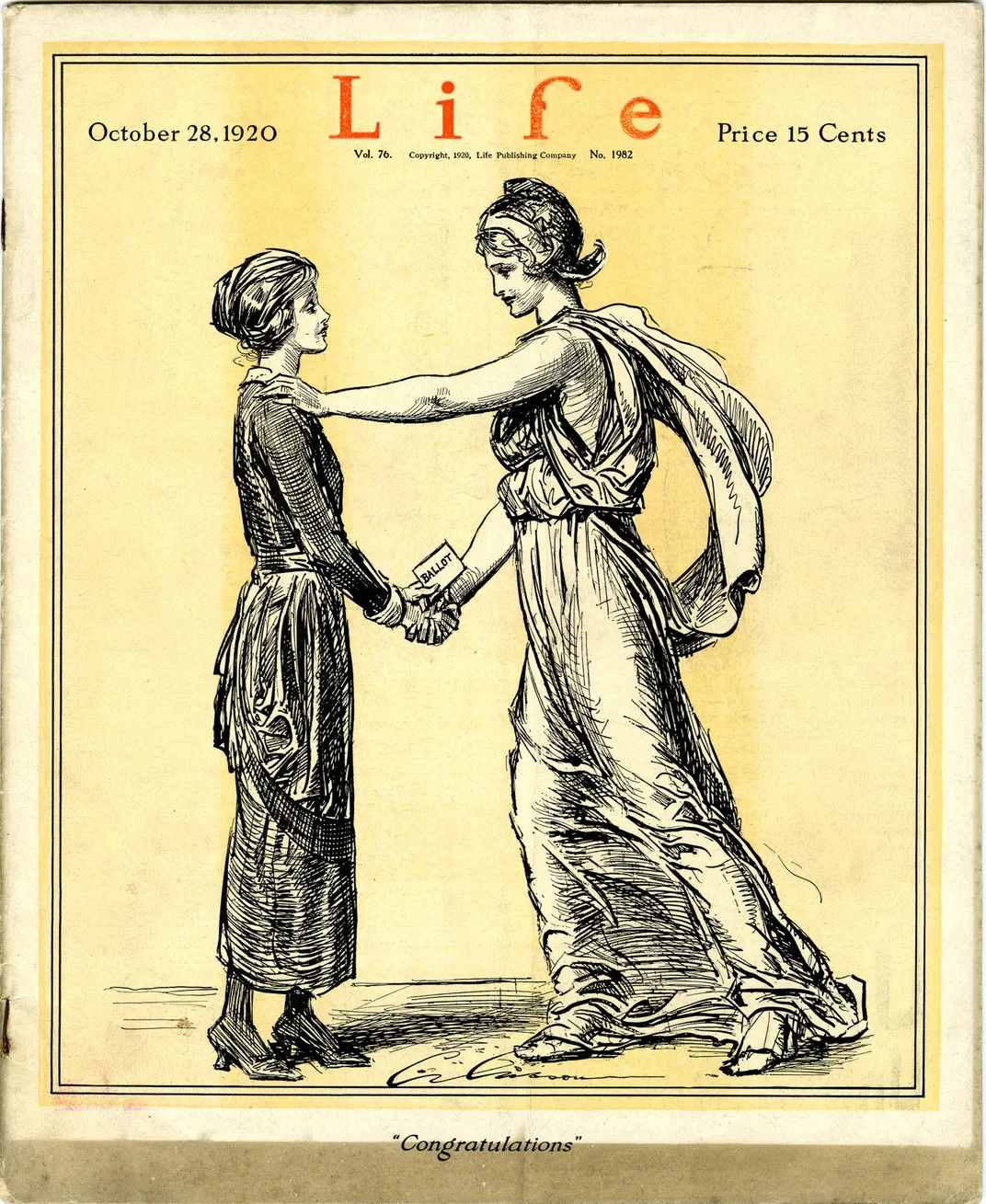

The struggle for women’s suffrage in the United States started on July 19, 1848, when women’s rights activists and allies gathered in Seneca Falls, New York. The Declaration of Sentiments, modeled on the Declaration of Independence, enumerated “a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.” Suffragists wrote, “We insist that they [women] have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.” For the following seven decades, they would campaign for women’s right to vote, enduring splinters within their movement and combatting anti-suffragists, while trying to sway the American public and politicians to their cause.

The amendment to at last extend the franchise to women first passed the U.S. House in 1918 and the Senate the year after, and then, as called for in the Constitution, it was time for three-quarters of the state legislatures to approve it. In the end, it came down to one state and one legislator’s vote. The final battle in the fight was pitched during a muggy summer in 1920 in Nashville, Tennessee. A comprehensive new book, Elaine Weiss’ The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (out on March 6, 2018), goes inside the fiery final debate over the 19th Amendment.

While we know how the story ends, Weiss’ book is still a page-turner. Following central figures, like Carrie Chapman Catt of the mainstream National American Woman Suffrage Association, Sue White, who worked for Alice Paul’s more radical Women’s Party, and Josephine Pearson, who led the anti-suffragists, Weiss explores the women’s motivations, tactics and obstacles. She takes readers to the halls of the city’s Hermitage Hotel, where lobbying swayed lawmakers, and to the chambers of the statehouse where last minute changing of votes made history.

Mostly importantly, Weiss’s book resists the notion that suffrage was something men graciously gave to women, and that this victory was inevitable. Many women fought passionately for their right to vote, battling against men, and other women, who wanted to keep it from becoming law. The Woman’s Hour shows suffragists doing the hard work of politics, including canvassing, lobbying and negotiating compromises. Smithsonian spoke with author Elaine Weiss about her new book.

The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

The nail-biting climax of one of the greatest political battles in American history: the ratification of the constitutional amendment that granted women the right to vote.

How did the battle for women's suffrage all come down to Tennessee?

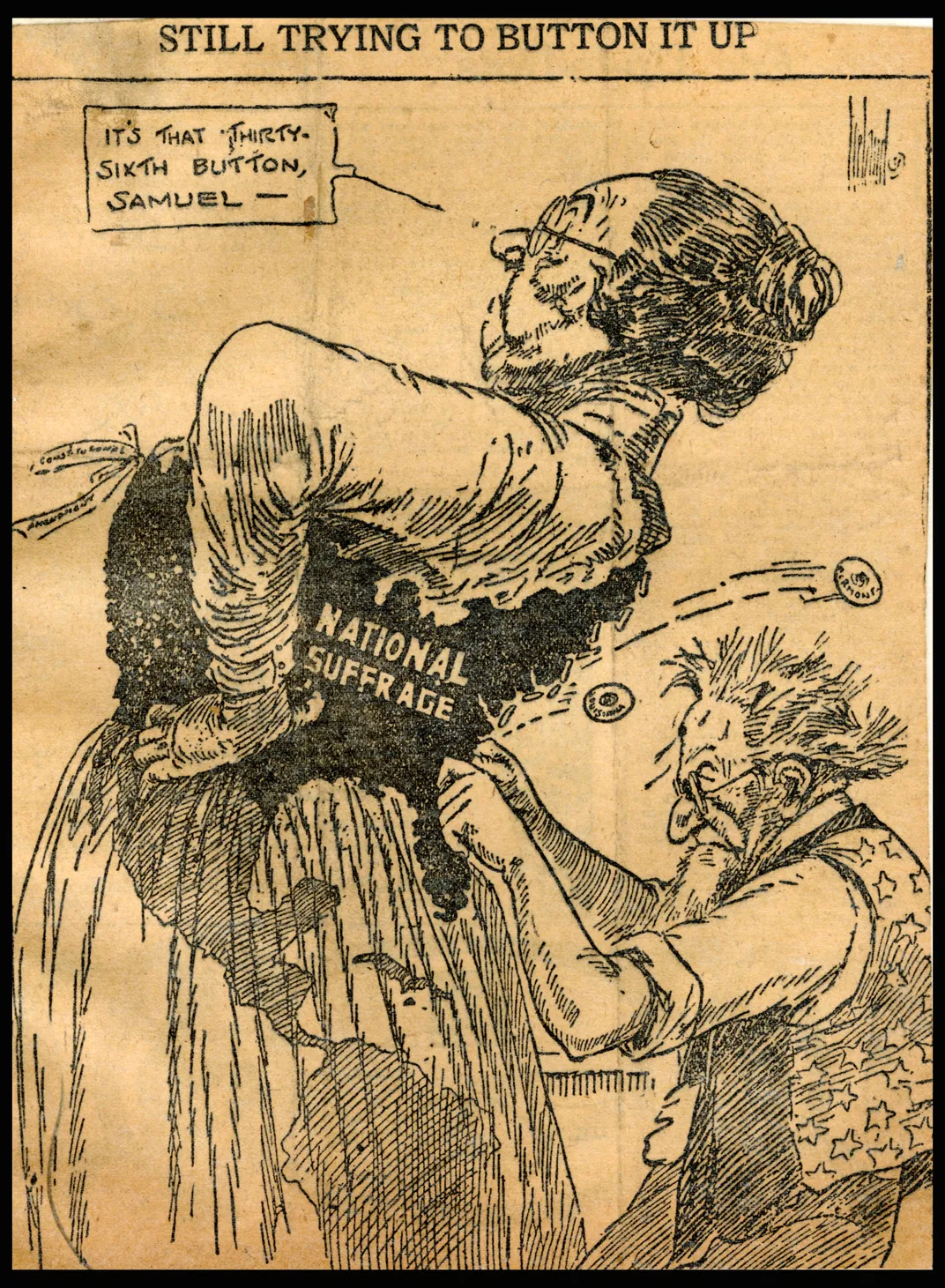

By 1920 we're talking about no longer getting resolutions or referenda in the states to allow women to vote state by state. It's finally come down to an amendment to the Constitution. In January 1918, the House passes the federal amendment, but the Senate refuses to, and it takes another year-and-a-half until World War I is over. It's in June of 1919 that the Senate finally relents [to consider the amendment]. They actually reject it twice more and then finally June of 1919 it is passed by Congress and it goes through the ratification process. Three-quarters of the states have to approve the amendment. There are 48 states in 1920, so that means 36 states have to approve it.

It goes to the states, and it's a very difficult process because one of the things that the [U.S.] senators did to make it harder for the suffragists, and very purposefully so, was that they held off their passage of the amendment until it was an off-year in state legislatures. At that time, most state legislatures did not work around the calendar. Lots of governors didn't want to call special sessions. But there’s a Supreme Court decision around this time that says amending the Constitution has its own laws and they take precedence over any state Constitutional law. The legislature has to convene to confront whatever amendment comes down to them.

After a recent defeat in Delaware, and with no movement in Vermont, Connecticut and Florida, suffragists turn to Tennessee, one of the states that hasn't acted yet. Even though it's a southern state, is considered a little more moderate than Alabama and Mississippi who have already rejected the amendment.

What would the fight for suffrage have looked like if ratification in Tennessee failed?

If you look at the score card, that would've been the 10th state that had rejected it. Thirteen would put it over the threshold of not having 36 states accept it. This is the pivotal moment: anti-suffragists see that if they can thwart ratification in Tennessee then things may really start to change. The anti-suffragists are also fighting to re-litigate in certain states where the amendment's been accepted. They're going back into court in Ohio, in Texas, in Arkansas and saying, we see irregularities and we want to expunge the ratification in these states. If they do this in a few more states, and if they're successful in the state courts, it might happen.

Does it mean that it would never have been ratified? Probably not. But after the war, Carrie Catt, the leader of the mainstream suffragists, and Alice Paul see that the nation is moving into a more conservative, reactionary frame of mind. They sense it by the presidential candidates. You have Warren Harding for the Republicans saying he wants a “return to normalcy,” and everyone understands what that means. No more Progressive era, no more getting entangled in international wars, no more League of Nations, and they can see that the nation is moving in a way that women's suffrage might not be part of the agenda anymore.

It would probably have retarded the progress of nationwide suffrage for a decade or so at least. Then who knows, then you have to get it through Congress again and all that. It's hard to say that women would never have gotten the vote by federal amendment, but it certainly would've been very much delayed and perhaps for a significant amount of time, because they’d lost momentum.

Race played a surprising role in the ratification fight.

The federal amendment held the promise—or the threat, depending on your point of view—of black women voting. Politicians were nervous about this, while the southern anti-suffragists used it as ammunition for opposing the amendment. The suffragists tried to appeal to a wide range of people, including those who were racist, by saying “white women will counteract the black vote.” They were willing to use what we would see as racist arguments to get the vote for all women.

They know what they're doing. Not to say there aren't some blatant racists among the suffragists, but from what I could see this is a blatantly political move that they need to keep this coalition together and they will make whatever arguments seem to assuage any doubts in the southern states.

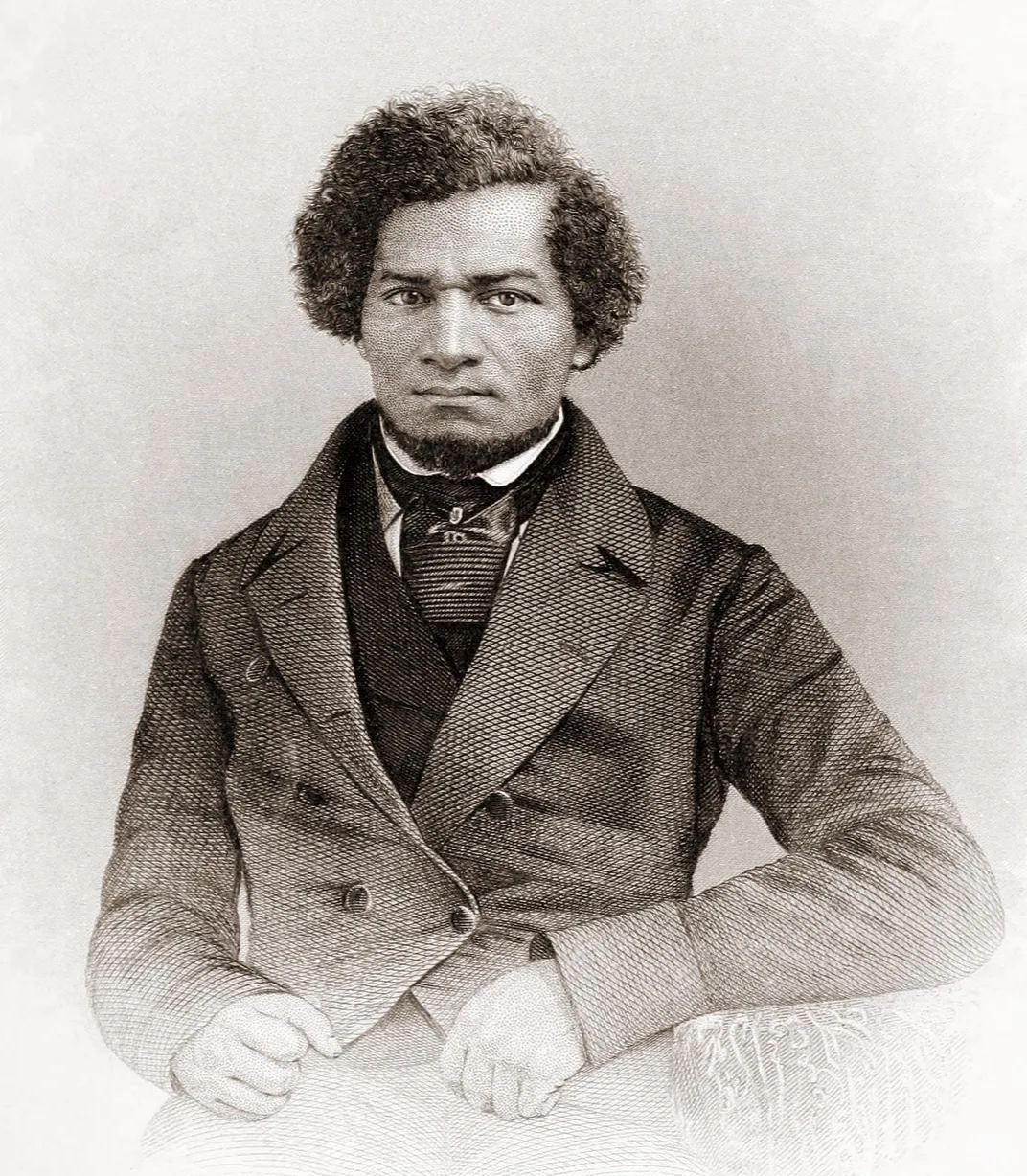

You do have Susan B. Anthony who really does, in her work and in her life, want to erase the kind of structural racism that she sees. She is personal friends with many black Americans, but she too asked Frederick Douglass not to come to the first suffrage convention that's held in Atlanta. She says she doesn't want him to be humiliated there, but you can see it in another way that she doesn't want to antagonize the white women who are there. You see this over and over again. It's hard to see these women who are fighting for democracy to succumb to this kind of racist approach.

We think of money's role in politics as new, but the suffragists had to overcome that.

The forces against suffrage are very familiar to us today. There was a lot of money in the anti-suffrage campaign from the liquor industry, because many suffragists also supported the temperance movement, and from the manufacturers, because women voters might want to outlaw child labor. They were against suffrage because it would be bad for business.

What does conventional wisdom get wrong about the suffrage movement?

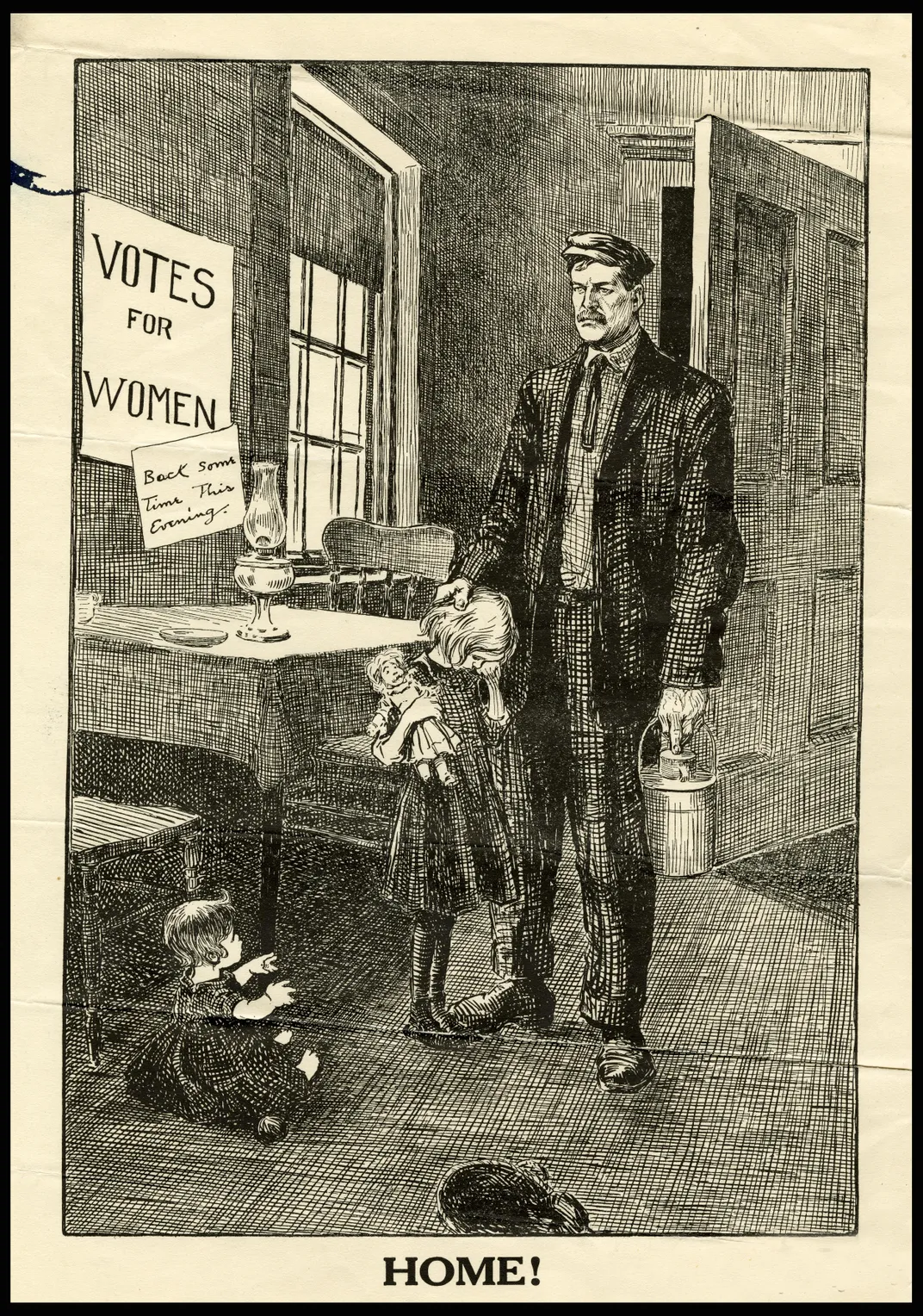

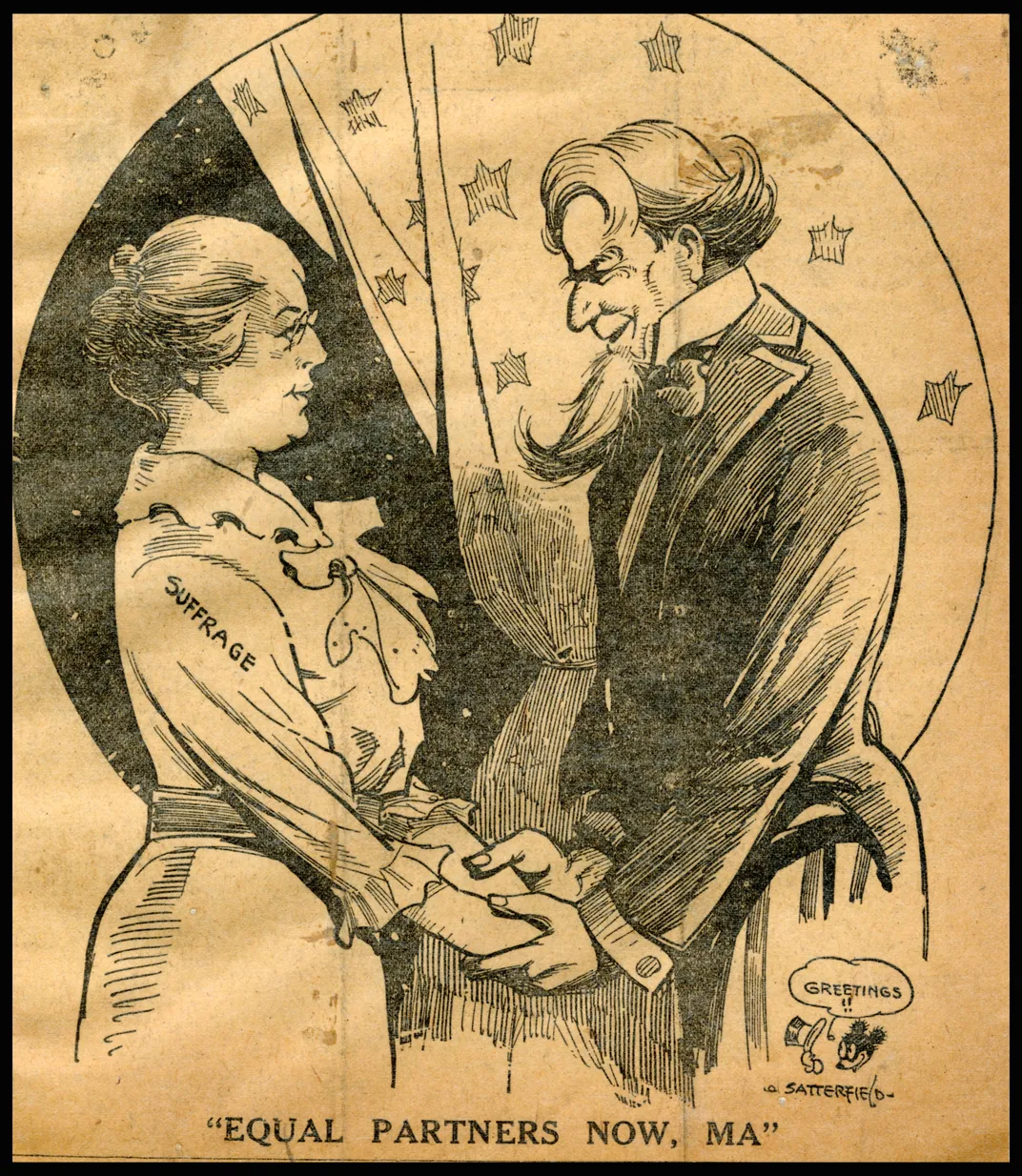

This was a much more complicated story than we've been led to believe or think we know, that it brings together a lot of the issues that are themes of American history, which is racial animosities, corporate influence in our government, the role of the church and religious thought and what is its place in public policy, and the whole idea that women are not of one mind.

There are women who opposed suffrage and, of course, there are women who vote very different ways now. You see all of these elements of American history and what we're still dealing with today as a microcosm in Tennessee. That's what I found so fascinating about it, that it wasn't just a fight for suffrage. This was a cultural war, but it was also a political war. It was a hearts and minds kind of battle where we were deciding on a whole new idea of what women's citizenship was. We were also deciding what kind of democracy we wanted, and we're still having that conversation today.

Women’s suffrage is usually seen as an event: men gave women the vote. We don’t have a sense of the complexity of the issue, the politics involved or of the real sacrifices that these suffragists made. That means we don’t understand how our democracy changes. How aggressive do you have to be make it better? We still have a lot to learn about how social movements can change America.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.