Joe Pyne Was America’s First Shock Jock

Newly discovered tapes resurrect the angry ghost of Joe Pyne, the original outrageous talk show host

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/85/6685f2ce-0bc2-48b4-b058-3a4c350aa3c5/jun2017_h05_prologue-wr.jpg)

A blurry image on a TV screen:

A sandy-haired talk show host leans toward a microphone. “My name is Joe Pyne,” he says, “and the action starts right here.” On the screen, it’s 1967. Soon he introduces a guest, campus radical Jerry Rubin, a leader of what Pyne calls “the free speech, filthy-speech movement.” Soon they’re arguing. Pyne calls Rubin an outlaw. His studio audience boos as Rubin stalks off the stage. “This is a circus,” Rubin says, “and you’re a fool.”

“You’re a liar,” says Pyne, “and a danger to the country!”

Then his face turns green and dissolves in a flurry of static.

Charles Churchman throws a switch on a half-ton video console in a converted barn in Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania. “Well, that won’t do,” he says. The oversized reel-to-reel console, complete with wave-form monitors and oscilloscopes, looks like a relic of the Gemini program. Churchman, 69, restores obsolete videotapes in his cluttered workshop. Twisting dials and pushing buttons, he reverses the crinkly 50-year-old tape in the machine, clears a dot of rust from it, restarts the tape, color-corrects the image. “That’s better,” he says. “I mean, Joe Pyne was a lot of things, but he wasn’t green.”

Churchman is one of several techies, archivists and vintage-TV fans who hope to save “The Joe Pyne Show” from history’s scrapheap. He’s the mad scientist of the bunch, a self-taught engineer who can transform strips of moldy, decades-old videotape into crisp digital images. He first heard about Pyne from his client Alexander Kogan Jr., president of Films Around the World, a decade ago. Kogan, whose firm restores and markets classic movies and TV programs, had discovered a trove of long-lost tapes in his collection: more than 100 episodes of Pyne’s once-famous talk show on reels of two-inch videotape that weighed 28 pounds apiece. Many were in bad shape, the iron oxide that fixed the image to its acetate base flaking off. Churchman, the video savant, restored a few at a time. He has yet to work on dozens of tapes that feature interviews with some of the most polarizing figures of the 1960s.

Today he’s working on a rust-specked reel recorded in a Los Angeles TV studio 50 years ago.

Churchman starts by warming the tape in an incubator he bought secondhand. The incubator bakes out moisture that can ruin old videotapes. Another machine removes dust, rust and mold. “We treat each tape as if it’s a final ‘suicide run’ through the tape machine,” his client Kogan says of the transfer from decaying acetate to digital files, a process that preserves the image and sound before the tape can self-destruct. Why bother? “Because he was important,” says Kogan. “Pyne set the tone for so much of what we see on our ‘news’ channels every day and night. The confrontation, the anger, the yelling. But who remembers his name?”

Nearly forgotten today, Joe Pyne ran roughshod over America’s airwaves in the 1950s and ’60s. A charismatic bully in a jacket and tie, he grilled hippies, Black Panthers, “pinkos,” “fairies” and “women’s libbers,” practically inventing the attack interview. The New York Times called him “the ranking nuisance of broadcasting...hitting a jackpot by making a virtue of bad manners and wallowing in the cheap sensationalism of an electronic peepshow.” To Time magazine he was “Killer Joe, host of a tasteless electronic peepshow.” By 1968 Pyne had more than ten million viewers a week—comparable to the audience Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity and Megyn Kelly combined to reach last year.

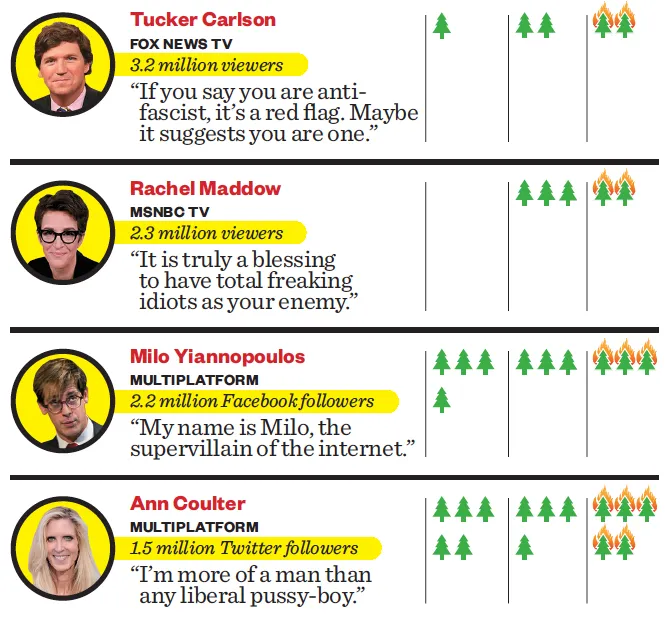

According to media historian Donna Halper, author of Icons of Talk, “Pyne was one of broadcasting’s truly unique figures—the original angry talker. He rose from the lowest level of radio and founded the modern TV shoutfest.”

And then, just as quickly, he was gone.

**********

Born in Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1924, Joseph Edward Pyne was the son of a bricklayer. For years, he stuttered. He was the kind of kid schoolmates mocked. In 1942 the newly minted Chester High School graduate joined the Marines. Shipped to Okinawa, Private Pyne won three battle stars for valor in combat, plus a Purple Heart for a shrapnel wound to his left knee. After the war he cured his stutter by enrolling in a drama school. In one account the tongue-tied war vet sputtered while other students spoke like budding Oliviers and Hepburns. But he kept at it, doing vocal drills for hours on end. When he finished his first Shakespeare scene, his classmates stood and cheered.

Pyne talked his way into a job at a radio station in North Carolina and was promptly fired. He bounced around local stations, landing at WLIP in Kenosha, Wisconsin, when he was 24. “He took song requests from listeners who phoned in,” recalls WLIP veteran Lou Rugani. “He wanted to chat with them, but in those days there was no way to put a phone line on the air. Joe would say, ‘Uh-huh,’ and ‘Mm-hm,’ then tell listeners what the caller said.”

One caller objected to the young D.J.’s pro-union opinions. “Do you know anything, sir, about the history of labor-management relations?” Pyne asked the man. After a moment of dead air he continued, “No, you keep your voice down....” Pyne was an expert interrupter, but this caller barely paused for breath. Listening, Pyne had an idea. According to Rugani, “He held the phone receiver to his microphone. Now the caller’s live on the air. And call-in radio was born.” Other radio hosts would make similar claims through the years, but there is no doubt that Pyne pioneered the format in Kenosha in 1949.

He figured he deserved a raise. His boss disagreed. Another WLIP host, Irene Buri Nelson, heard a commotion and peeked into the boss’s office. “Joe was yelling,” she recalled. “He had one hand on our boss’ lapel. He picked up a typewriter and threw it against the wall.” Pyne stalked out—unemployed.

During a stint at WILM in Wilmington, Delaware, he married a beauty queen but proved no more tractable as a husband than he was as an employee. They divorced a year later. In 1951 his war wound acted up. Complications set in. Surgeons saved his life by amputating his left leg from the knee down. Within weeks he was back in the studio, limping on a prosthesis. He never spoke of his wooden leg on the air or in public; co-workers knew never to mention it.

Climbing the radio ladder from Wilmington to Philadelphia, Pyne grew more conservative. In 1953, when the United States electrocuted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, he exulted. “We finally incinerated those commies,” he rejoiced on the air. “I hope it was slow and painful.”

His first TV talk show flopped, but a stint on Philadelphia’s WVUE-TV made him locally notorious. KTLA-TV lured him to Los Angeles with an offer of $1,000 a week—more money per year than the Yankees paid Mickey Mantle. Soon Pyne was a top-rated talk show host in the nation’s second-biggest market.

At a time when TV’s leading men included Walter Cronkite, Edward R. Murrow, Andy Griffith and Captain Kangaroo, Pyne was the medium’s first shock jock, a firebrand who invited hippies, civil-rights activists and Ku Klux Klansmen alike to “Take a hike” or “Go gargle with razor blades.” By the mid-’60s, he was the most popular TV-radio voice in America. Johnny Carson had more television viewers, but Pyne, with his syndicated TV show and 200-plus radio outlets, had an audience to rival Johnny’s. Life magazine called him “sadistic...a barroom tough,” but millions tuned in to watch the fireworks. When a guest advocating “free love” set off a melee, Pyne’s audience charged the set and knocked it flat.

One guest, the suave TV personality David Susskind, earned a chorus of boos for calling Pyne’s program “an orgy for morons.” Host and guest both got a kick out of that.

In fact, Pyne wasn’t as one-dimensional as he seemed. While railing on-air about bombing Vietnam back to the Stone Age, he once helped ship supplies to Vietnamese villages. While devoting a show to “the angry Negro,” he threatened a black-power campaigner by showing off the revolver he carried. Yes, Pyne was packing. But he also welcomed black activist Maulana Karenga, who invented a holiday called Kwanzaa. In another episode, Pyne mocked Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown, calling her a “dingbat,” and invited her to explain why “girls” could be as good at their jobs as men. When she finished, he applauded.

When Christine Jorgensen appeared on “The Joe Pyne Show,” he was polite, even gallant, to her. Maybe that was because they had something in common. Christine, born George Jorgensen, was a fellow World War II veteran.

Other times, he was as abrasive as you’d expect. In 1967 he introduced Paul Krassner as “the publisher of The Realist, a filthy, avant-garde, left-wing rag.” Fifty years later, Krassner recalls thinking, Well, I don’t know about “rag....”

“Why do you print the most obscene words?” Pyne demanded. “Do you edit your magazine because you were an unwanted child?”

“No, Daddy.”

Their talk went downhill from there. “He asked me about my acne scars,” says Krassner, now 85. “That was a low blow. I said, ‘Let me ask you something: Do you take off your wooden leg before you make love to your wife?’ And his jaw dropped.” According to Krassner, the audience gasped while Pyne’s producers “averted their eyes and the atmosphere became surrealistic.” Krassner laughed all the way home. If this was the worst the establishment could do, maybe the revolution was coming after all.

While any on-air mention of his wooden leg was taboo, Pyne wasn’t always so touchy. One of his nieces recalls her famous uncle as a funny, generous fellow who invited his nieces and nephews to kick his peg leg. It was such fun that they ran to get their friends, and the neighborhood kids lined up to kick Uncle Joe.

In 1965 the 40-year-old star married Norwegian model Britt Larsen, 21, in Las Vegas. When the newlyweds went to Frank Sinatra’s show at Caesars Palace, Sinatra asked “the great Joe Pyne” to stand and take a bow.

Pyne’s $4,000-a-week salary doubled that of President Lyndon Johnson, whose Vietnam War he supported. And he was determined to enjoy his success. The Pynes’ house in the Hollywood Hills featured smoked-mirror walls, velvet furniture, a swimming pool and a driveway stocked with a Triumph, an Aston Martin and a Rolls Royce. Sometimes he parked the Rolls near his studio on Wilshire Boulevard. “He didn’t want his car to get vandalized,” recalls his former producer Stuart Levy, “so the station hired a guard to watch the car while Joe was on the air.” Pyne sailed his custom-designed yacht to Catalina Island. Like many a former infantryman who envied fighter pilots, he wanted to fly. Flying figure eights over Santa Monica, he used a special stirrup to work the left rudder pedal with his wooden leg. “Joe took me up in a Piper Cub. It was my first airplane ride,” his brother-in-law Jim Mockler recalled years later. As they headed for Flagstaff, Arizona, “He told me to watch out for planes we might bump into.” It gets cold in Flagstaff—the runway was covered with snow as they tried to land. Mockler held on as Pyne brought the little plane to a skidding stop. “I asked Joe if he’d ever landed in snow. He said, ‘Hell, no, but wasn’t it fun?’”

“Joe Pyne was a hustler and a bully,” says author Harlan Ellison, a Los Angeles Free Press columnist in the ’60s. “And he was sharp. I thought I’d go on his show and beat him at his own game, but I blew it. I spent my time talking about the issues, civil liberties and all that, and he talked about America. The trouble with Pyne was that he was really, really good at what he did.”

As riotous 1968 led to 1969, Pyne found it harder to breathe. Tests led to a diagnosis of lung cancer. For years he had referred to the cigarettes he smoked on the air as “coffin nails,” a term he helped popularize. He’d always sworn he would never stop smoking, but now he quit cold turkey. Too late. Too weak to drive to his TV studio, he hosted “The Joe Pyne Show” from home. His wife tended him to the end, when he broadcast from his bed, denouncing enemies like the “peace creeps” who opposed the Vietnam War. As one listener recalls, “He was lying in bed in his jammies, yammering insults,” raging against the dying of the red light.

**********

Pyne died in 1970. He was 45. Had he lived, he might have lasted long enough to lecture Hannity, Howard Stern, Bill Maher, Rush Limbaugh and other rabble-rousers on how much they owed him. “When it comes to manipulating media,” says media critic Halper, “he was the father of them all.”

One of Pyne’s protégés, the controversial radio shouter Bob Grant, followed his mentor Pyne as a talk show shouter in Los Angeles before moving to New York, where Grant paved the way for his successor at WABC, Sean Hannity. Hannity had first gained national attention subbing for Rush Limbaugh, another Bob Grant fan. When Grant died in 2013, Hannity hailed him as “one of the greatest pioneers of controversial, opinionated talk radio.” Grant, in turn, had acknowledged his debt to the founder of in-your-face talk. Even Vice President Mike Pence, who hosted a right-wing talk show in Indiana in the 1990s, was a successor of Pyne’s. (Soft-spoken Pence described himself as “Rush Limbaugh on decaf.”) According to Harlan Ellison, who admired Pyne’s shrewdness while loathing his politics, “I’ve appeared on that sort of show all over the country. They call it controversy, but they’re all about vilification and hostility, and their model is Pyne.”

Yet his show disappeared after Pyne died. Because videotape was expensive, producers taped over “Pyne Show” episodes or cut them into one- and two-minute strips to use for commercials—the same process that destroyed the first decade of Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show.” “It was a shame, and not just because he invented the sort of angry TV talk we see so much today. He was a masterful interviewer,” says Kogan of Films Around the World. Kogan’s New York City warehouse holds film, video and digital versions of everything from Nosferatu to 1940s musicals to cheesy soft porn to Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter. After he found hundreds of Pyne tapes in a collection he’d bought from another firm, he pulled a handful and salvaged them. The rest—including potentially valuable releases signed by Pyne’s celebrity guests—wound up in filing cabinets and cardboard boxes in Providence, Rhode Island. “Then we shipped them to a storage space in the basement of the Quad Cinema in Manhattan. We also had tractor-trailers full of stuff in Long Island City.” All those moldering tapes and documents represented a unique slice of ’60s America: Pyne’s talks with American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell, celebrity lawyer F. Lee Bailey, authors Tom Wolfe and Jacqueline Susann, wrestling kingpin Freddie Blassie, stripper Candy Barr, segregationist Georgia governor Lester Maddox, and many more.

It’s hard telling who else might be squaring off with Pyne in the stack of tapes in Churchman’s workshop, near Philadelphia. Many are unmarked, unwatched for half a century.

With help from Churchman and another tech whiz, Jim Markovic, Kogan intends to save as many Pyne shows as he can. After that he’ll sell them on DVD, or maybe stream them. His fondest hope is to resurrect Pyne on TV Land or another cable channel. “He deserves it,” Kogan says, “and I want to be the guy who saved Joe Pyne for a new generation of people who watch TV.”

He would love to come across a fabled exchange between Pyne and Frank Zappa. According to Pyne lore, he invited his audience to “Say hello to a musician—and I use that term loosely—representing a rock ’n’ roll band known as the Mothers of Invention.”

Zappa, 24, nodded to the booing crowd. Pyne looked him over and said, “I guess your long hair makes you a woman.”

Zappa shrugged. “I guess your wooden leg makes you a table.”

If they find that one, it’ll be news. Meanwhile Kogan, Churchman and a loyal crowd of Pyne fans hope to keep Killer Joe’s memory alive. “People ask me if he was like Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly,” says Levy, who produced Pyne shows half a century ago. “I say yes—but Joe got there first.”

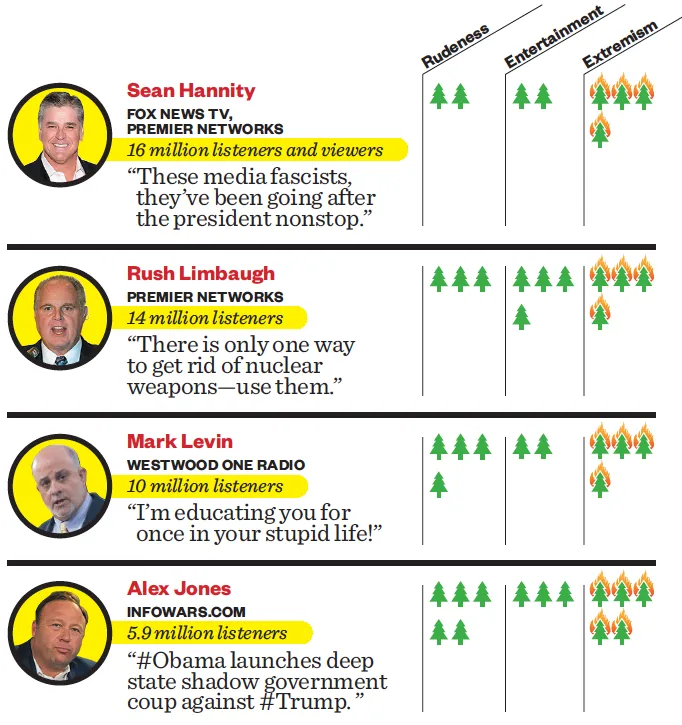

The Spiritual Descendants of Joe Pyne, the Original King of Conflict

Icons of Talk: The Media Mouths That Changed America (Greenwood Icons)