In the Event of War

How the Smithsonian protected its “strange animals, curious creatures” and more

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/treasures-guard.jpg)

On September 7, 1940, some 340 German bombers darkened the skies over London and launched the intense bombing campaign that came to be known as the Blitz. During this period, the Germans bombed military and civilian targets, destroying hospitals, schools, water works and libraries. In addition to killing thousands of people, these attacks—which didn't conclude until May 11, 1941—destroyed government records and damaged cultural treasures, including the British Museum, the Houses of Parliament and St. James's Palace.

There was no guarantee that the United States—Washington, D.C. in particular—would be spared a similar fate. So by the close of 1940, the heads of various U.S. federal agencies, including the Library of Congress, the National Park Service, the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian Institution, met to discuss the protection of the country's cultural treasures. The resulting Committee on Conservation of Cultural Resources was formally established in March 1941 by the president of the United States.

By early 1941, the Smithsonian had surveyed its important scientific and irreplaceable historic materials. Most of the items chosen for evacuation were type specimens—the original specimens from which new species of plants or animals have been described, which serve as a standard for future comparison—from the natural history and paleontology collections. As Assistant Secretary Wetmore noted in a 1942 letter, the Institution also considered "strange animals from all parts of the world, curious creatures from the depths of the sea, plants from China, Philippine Islands, South America and so on, historical objects of great importance, as well as curious types of ancient automobiles, parts or early airplanes."

After studying British and European conservation models, the cultural resources committee decided to build a bomb-resistant shelter near Washington, D.C. for the evacuated collections. The Federal Works Agency was assigned the job of constructing the buildings, but a lack of funding and shortage of manpower delayed the project.

This wasn't the first time the Smithsonian was required to protect its collections. Late in the Civil War, when the Confederate Army reached the outskirts of Washington and threatened to invade the city, a room was prepared under the south tower of the Smithsonian Castle to store valuables. Secretary Joseph Henry was issued 12 muskets and 240 rounds of ammunition for protection against "lawless attacks."

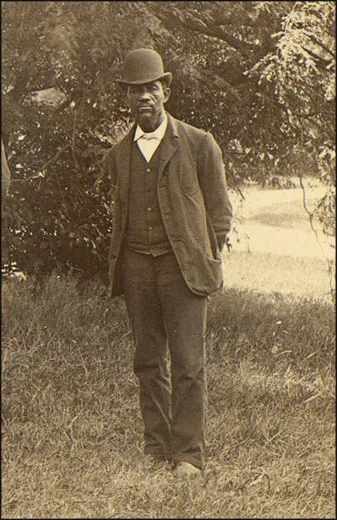

In a letter dated July 15, 1864, Solomon G. Brown, a general laborer and clerk who served under assistant secretary Spencer Baird, and who wrote to him almost daily, noted: "All here is well—many have been much frightened at the annual visit of the Rebels to their friends at Maryland, but we are told that the johny Rebs are returning home.... I had prepared aplace in center of the cole celler under south tower under stone floor for the deposition of a box of valuables committed to my care should any thing suddenly turn up to prevent them being shipped to a place of safty outside of town." The contents of the box are unknown.

When America entered World War II on December 8, 1941, the need for protection became more urgent. A warehouse in Shenandoah National Park near Luray, Virginia, offering 86,000 cubic feet of storage space, was declared suitable for the Institution's needs, and Smithsonian departments scrambled to submit their space requirements.

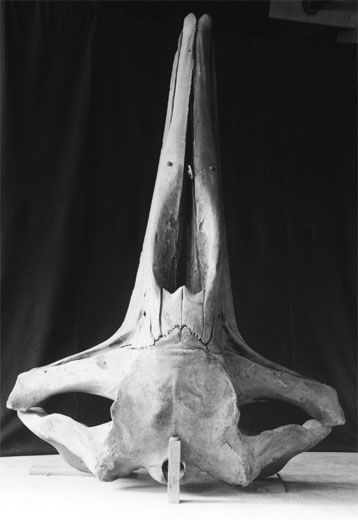

The Natural History Museum's department of biology requested a whopping 2,497 cubic feet just for its collection of mammals, which included the skulls of two beaked whales, various hippo, sheep and caribou, and a cast of a porpoise. The department of engineering and industries asked for 10.5 cubic feet for the storage of an 1838 John Deere steel plow, and another 125 cubic feet for "20 of the most important original patent models," as well as space for a portrait of Charles Goodyear "on a hard rubber panel." The National Collection of Fine Arts requested 10,000 cubic feet for its paintings, frames removed, including Thomas Moran's unusually large Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The Division of History packed the First Ladies' dresses, George Washington's uniform and field kit and Alexander Hamilton's table. The Star-Spangled Banner was shipped in a 15-foot-long, specially constructed box.

The selection process was not without conflict. When the division of history requested 250 boxes to pack up its collections, curator Carl Mitman, the evacuation project's warden, questioned the significance of some of the articles: "I readily admit that I am not qualified to approve or disapprove Mr. Belote's selection of material for evacuation. I would, however, call your attention to the fact that...51 boxes...are to be used for the packing of the plaster heads, arms, and feet of the figures on which the Presidents' wives' gowns are displayed. Are these materials irreplaceable?"

In addition to articles of historical significance, security precautions were taken for "objects which are on exhibition and which possess a monetary value easily apparent to the man on the street." Solid gold medals, sterling silverware, gem collections, jewelry and gold watches were the "likely pickings of the saboteur and petty thief following an air raid," warned Mitman. Many of these items were quietly removed from exhibitions and placed in bank vaults.

The evacuated treasures weighed more than 60 tons and were shipped to Virginia at a cost of $2,266 each way (more than $28,500 in today's dollars). They were placed under 24-hour guard until the war's end. The guards protected the collections against possible sabotage, theft, fire—and damage caused by a couple of errant pigeons who had made a home inside the warehouse.

By late 1944, the bombing of Eastern Seaboard cities appeared unlikely, and the National Park Service began the extended process of returning treasures to their original venues. But plans for safeguarding the Institution's irreplaceable objects didn't cease with the conclusion of World War II. The Smithsonian still has such policies in effect today, says National Collections Coordinator William Tompkins. Since the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C. on September 11, 2001, for example, the Institution has been moving specimens preserved in alcohol—often referred to as "wet" collections—off the Mall and into a state-of-the-art storage facility in Maryland. This move ensures that these rare specimens will continue to be available to researchers and scientists.

The Star-Spangled Banner, Lincoln's top hat, the Wright Military Flyer, and the millions of other icons in the collections will continue to be safeguarded, for, as Assistant Secretary Wetmore first wrote in 1942, "If any part of these collections should be lost then something would be gone from this nation that could not be replaced... ."