How One Amateur Historian Brought Us the Stories of African-Americans Who Knew Abraham Lincoln

Once John E. Washington started to dig, he found an incredible wealth of untapped knowledge about the 16th president

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/a8/49a897be-daa9-4a56-800a-cb4c25d32699/abraham_lincoln_entering_richmond_april_1865-wr.jpg)

The memoir of Elizabeth Keckly, a formerly enslaved woman who became a dressmaker to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, struck a nerve when it was published in 1868. Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House was an unprecedented look at the Lincolns’ lives in the White House, but reviewers widely condemned its author for divulging personal aspects of their story, particularly the fragile emotional state of Mary Lincoln after her husband’s murder.

For decades after its publication, the book was difficult to find, and Keckly lived in relative obscurity. In black Washington, however, many African-Americans personally knew and admired her, and she remained a beloved figure.

When journalist and Democratic political operative David Rankin Barbee claimed in 1935 that Keckly had not written the book and, remarkably, had never existed, one determined Washingtonian, an African-American high school teacher named John E. Washington, felt compelled to speak up. The encounter with Barbee about Keckly and Behind the Scenes changed Washington’s life and led him to write a remarkable book of his own—They Knew Lincoln.

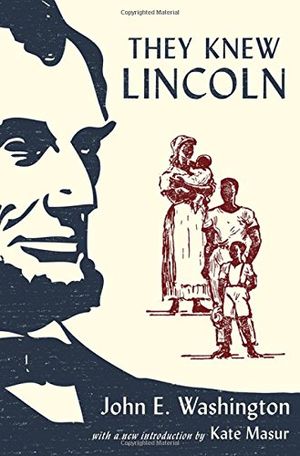

Part memoir, part history, part argument for the historical significance of common people, They Knew Lincoln was the first book to focus exclusively on Lincoln’s relationship to African-Americans. They Knew Lincoln not only affirmed the existence of Keckly, but revealed that African-Americans, from the obscure folk preacher known as Uncle Ben to the much more prominent Keckly, had shaped Lincoln’s life, and it insisted that their stories were worth knowing.

The book, reprinted by Oxford University Press this month, makes Washington’s research newly available to 21-century readers. The 2018 edition also includes my new introduction, adapted here, which sheds light on Washington’s life and how his pioneering work of history came together.

They Knew Lincoln

Part memoir and part history, the book is an account of John E. Washington's childhood among African Americans in Washington, DC, and of the black people who knew or encountered Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln.

A part-time dentist and full-time art teacher, owner of two homes, and a history buff, John E. Washington was a married man with no children in the fall of 1935 when he took it upon himself to contest the scandalous assertion that Elizabeth Keckly could not possibly have written Behind the Scenes.

David Rankin Barbee, a Washington, D.C., gadfly who regularly sought to explicate and defend the white South to outsiders, had offered his theory about the authorship of Behind the Scenes to up-and-coming Washington journalist Bess Furman. Furman, who wrote for the Associated Press and spent much of her time covering Eleanor Roosevelt, was interested in the history of women newspaper correspondents in Washington and had first sought Barbee’s expertise on Jane Grey Swisshelm, a Civil War–era correspondent from Minnesota. When Barbee told her that Swisshelm was the true author of Behind the Scenes, Furman believed him. Upon filing her story on this supposed new discovery, Furman jotted in her daily diary that the work revealed “Madame Keckly the Negro seamstress . . . being really Jane Swisshelm, the best darned newspaper woman out blazing trails.”

Furman’s piece ran in the Washington Star on Saturday, November 11. Four days later the paper published John E. Washington’s refutation. Washington established his authority by stating “that for over 30 years, I too, have been a close student of Lincoln” and that he possessed “some of the rarest items pertaining to the assassination period.” From there, Washington insisted that Keckly had indeed lived and that, while others might have helped her write the book, Keckly had taken “full responsibility” for it.

Barbee quickly countered with his own letter to the editor a few days later, claiming he had never denied Keckly’s existence but, instead, had argued that “no such person” had written Behind the Scenes. He maintained that position, reiterating that Swisshelm was the real author and that Behind the Scenes was a work of fiction.

His claim rested on the thinnest of evidence—one line of a satirical news item written in 1868 that had noted “Swizzlem” in the gallery of the Senate and nonsensically identified her as “the colored authoress of Mrs. Keckly’s book.” But that tiny clipping was probably far less important to Barbee than his deeply held beliefs about race and gender. No one, he told a friend in private correspondence, could “find in all the United States of 1869 [sic] one negro woman who had enough culture to have written such a book.”

Meanwhile, he insisted, Mary Lincoln “was not the type of woman who would gossip before servants. No well-bred Southern woman would do that.” He also claimed (incorrectly) that Mrs. Lincoln bought all her dresses in New York and Paris and had no need of a fine seamstress in Washington.

Barbee’s condescension toward African Americans knew few limits. In a letter to a white Lincoln aficionado, Barbee called the Washington Star the “Negroes’ newspaper Bible.” He told Louis Warren, whose newsletter, Lincoln Lore, had cited an early 20th-century interview with Keckly to challenge Barbee’s assertions, that Keckly was evidently the “patron saint” of Washington’s African-Americans and warned: “Had you, like myself, grown up among Negroes in the South—we had a family of them under our roof for many years, and educated them—you would be skeptical about what any old colored woman eighty years old might say.”

Barbee insisted to Warren that there was no evidence “acceptable in the court of history” that Keckly had ever worked for Mrs. Lincoln or Varina Davis, as stated in Behind the Scenes. Over and over again he told acquaintances that black people’s memories were faulty and that Washington’s research was poor.

On learning of black Washingtonians’ strong objections to Barbee’s claims, Furman decided to investigate further. “Someone who knew Madame Keckly turned up,” she recorded in her calendar a few days after the initial story ran. She headed to the home of Francis Grimké, Keckly’s former pastor, who had a photo of Keckly and talked extensively about having known her and preaching at her 1907 funeral service. Soon Furman was at Washington’s home, interviewing him about Keckly and taking down the names and addresses of other black Washingtonians who could attest to her existence. Furman’s new story, which she privately called a “correction,” went over the AP wire and appeared in the Washington Star on December 1. Barbee’s assertions had “brought Negro leaders forward in spirited defense of Elizabeth Keckly as an author,” Furman wrote. “In old albums they found photographs of her to prove her a decidedly dressy and intelligent person.”

At that point, Washington thought it possible that Swisshelm had persuaded Keckly to tell her story and that Swisshelm might even have “rearrange[d] the matter in good form and English for the publishers.” He was certain, however, that the stories contained in the book were true and that Keckly had been Mrs. Lincoln’s confidante.

The experience with Barbee confirmed something Washington had observed as a boy: African-Americans harbored, in their homes and in their memories, great quantities of meaningful history, untapped and at risk of being forgotten or even destroyed. His long-standing interests in both Lincoln and African-American history converged as he envisioned further research and a pamphlet that would vindicate Keckly. By 1938, he was deeply engaged in collecting further information about her, conducting interviews with local people and taking a summer trip to the Midwest for more digging. He had launched a new phase of his multifaceted life.

At first he imagined writing a pamphlet that would explain who Keckly was and how Behind the Scenes came into existence, but the project expanded as he became increasingly interested in the largely unknown lives of the African-American domestic workers the Lincolns had known in Springfield, Illinois, and Washington, D.C. The work required not just reading and interpreting documents but also dedication, creativity and a willingness to travel to new places and talk to living people. He conducted research in collections across the Southeast and Midwest. He interviewed elderly African Americans in Washington, Maryland, Virginia, and Illinois. And he reached out to the foremost Lincoln scholars and collectors of his era, hoping for leads and new information. This would be a book on the “colored side of Lincolniana,” he told one of his correspondents.

As he pursued his research, Washington began to make inroads into the white Lincoln establishment. A culture of Lincoln fandom had flourished in the wake of Lincoln’s 100th birthday in 1909, as Americans hunted for new stories about the man many considered the nation’s greatest president. Amid jokes about the quantities of Lincoln books published and whether anything remained to say or discover, hobbyists searched out autographed Lincoln documents and debated the minutiae of his life.

Interest in Lincoln grew in subsequent decades and reached its 20th-century apex during the Depression, when Americans of varying political stripes lauded him as a representative of perseverance through hard times and the dignity of common people.

The world of Lincoln buffs and collectors was diffuse, with local “roundtable” organizations operating relatively autonomously. Yet a measure of centralization existed through organizations such as the American Lincoln Association, based in Springfield, and the Abraham Lincoln National Life Insurance Company in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where Louis Warren directed the Lincoln Library Museum and published Lincoln Lore.

Washington’s path into that world began with Valta Parma, the curator of the Library of Congress’s Rare Books Collection who, early on, had affirmed Barbee’s thesis that Swisshelm had written Behind the Scenes. Parma was receptive to Washington’s research on Keckly and encouraged him to keep digging. He also helped Washington connect with leading Lincoln aficionados. Louis Warren was particularly helpful, encouraging Washington to write the book that would become They Knew Lincoln. “You could give us a very excellent story about Lincoln’s appreciation for his colored associates,” he wrote.

Washington took pleasure in the quest. Among the people he encountered was Aunt Vina, an old acquaintance of another elderly woman he knew from childhood. Driving a team of horses, Washington and his friend traveled hours to Aunt Vina’s remote and tidy home. “Unscrupulous relic hunters” had already been in the neighborhood and had “beaten” people like Aunt Vina “out of some of their most cherished objects.” Aunt Vina therefore talked about her experiences only after assurances from their mutual acquaintance that Washington was an honest man. Then she told of her experiences during the war: how her children had left to find work elsewhere but stayed in touch by mail; how she and her friends had traveled to the capital to witness Lincoln’s second inauguration; and how she had been among the mourners at Lincoln’s funeral.

In southern Maryland and Caroline County, Virginia, Washington also gathered African-Americans’ perspectives on the Lincoln assassination, a topic of perennial interest. Washington interviewed John Henry Coghill, an elderly man who said he had witnessed Booth’s demise on a Virginia farm at the hands of US soldiers. Coghill’s account of the capture and killing of Booth may have added little of substance to what people already knew of the incident, but Washington believed it important to publish Coghill’s verbatim testimony and his photo in They Knew Lincoln, giving him a voice and a place in history he would never otherwise have had.

Washington also included in the book interviews with two white men who he believed had something new to say about the assassination. One was Tom Gardiner, a dental patient of Washington’s who had been a close associate of the conspirators. The other, William Ferguson, was an actor who claimed to have been the only person who actually saw Booth shoot Lincoln—a vantage he had because of where he stood on the stage that night. Washington, always interested in art work and illustrations, had rare pictures of Ford’s Theatre and a diagram of the stage and seating. On the images, Ferguson made marks showing where he was standing and where the other actors were positioned. Washington, with a sense of duty to the historical record, published the picture with Ferguson’s annotations drawn in.

In the main, however, it was African-Americans’ perspectives that Washington sought to emphasize. The dignity and possibility of black history stood at the center of his endeavor. “I hope to produce a book with the soul of a disappearing people in it, and I think we have the material to do so,” Washington told one of the white Lincoln experts with whom he was in touch.

His emphasis on the validity and significance of African-Americans’ testimony about their own experiences and the nation’s history stood in stark contrast to others’ efforts to diminish Elizabeth Keckly. Washington filled his book with an accumulation of black voices, demonstrating convincingly that African-Americans had a great deal to say about the past and that their perspectives mattered.

As an African American, amateur historian, and outsider to the largely white world of Lincoln scholarship and collecting, Washington faced steep challenges in getting his book published. He hired Parma, the Library of Congress curator, as his editor and literary agent, and by fall 1940, Parma had secured contract with publisher E. P. Dutton. Despite some pitfalls along the way, They Knew Lincoln went into production in fall 1941 and hit stores in January 1942, carrying with it a strong endorsement by the famed poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg.

Newspapers and magazines across the country reviewed They Knew Lincoln, and most critics acclaimed the work as an important new contribution in the crowded field of Lincolniana. Many noted the unprecedented nature of Washington’s collection of African-American perspectives on Lincoln. Prominent actors dramatized portions of the book in a Harlem radio show, and the editors of an anthology of African American literature printed an excerpt. The book’s initial print runs sold out almost immediately. Yet Dutton never republished it, and copies became exceedingly hard to find. Scholars and collectors have been aware of the book as a valuable source for the history of the Lincolns and African Americans, but it has been inaccessible to the larger public until now.

*******

They Knew Lincoln piqued my interest many years ago when I checked out a copy from the University of Michigan library. I wondered who had written this unique work of history and memoir and how it had come into existence. They Knew Lincoln is the product of its own moment in time and of the particular interests of its author. It captures something important about the significance of Abraham and Mary Lincoln for many southern African Americans who lived through the Civil War. Many enslaved people interpreted the crisis of war and emancipation through biblical stories of Exodus and salvation, and they hoped and imagined that Lincoln would come among them and deliver them from slavery. Washington’s assertion of an earlier generation’s universal admiration does not tell a complete story, but it does reveal a crucial thread of African American thought, both during the Civil War and in the several decades that followed.

They Knew Lincoln was a forward-looking book. Washington’s compilation of former slaves’ views of Lincoln and his concern for the lives of everyday people, particularly as workers, represented an innovation not only in Lincoln circles but in the study of African-American history. During the 1930s, researchers were increasingly turning attention toward elderly former slaves, whose memories and perspectives they valued in new ways and sought to record. The most famous example of that impulse is the Slave Narratives project of the Works Project Administration, but African-American scholars like Washington led the way.

Moreover, through its national distribution by a major publishing house, They Knew Lincoln became the first book to bring black perspectives on Lincoln directly into the homes and collections of white Lincoln fans and the white reading public. The book’s very existence challenged people’s tendency to exclude or diminish the testimony of African-Americans, and it broke new ground by arguing that African-Americans were not simply passive recipients of Lincoln’s benevolence, but shaped his attitudes. Washington’s book remains a decisive reminder of the centrality of African-American history to the nation’s past.

From They Knew Lincoln by John E. Washington, with a new introduction by Kate Masur. Copyright © February 2018 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.