How the Alphabet Got Its Order, Malcolm X and Other New Books to Read

These five October releases may have been lost in the news cycle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/3e/d83e0db1-08a4-4c53-9e12-7dae097a469b/booksweek12.png)

Throughout history, alphabetical order has acted as an unsung agent of democratization, providing an organizational framework based not on social hierarchies, but an easily memorized string of letters. As historian Judith Flanders argues in A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order, “The religious no longer automatically took precedence over the secular, kings over subjects, or man over animals.”

In today’s Western world, the A-B-Cs are as self-evident as 1-2-3. But the adoption of an ordered Latin alphabet (the system used in most European and English languages) was far from straightforward. In fact, writes Flanders in the “first-ever history of alphabetization,” the protracted path toward alphabetical order spans millennia, involving such diverse entities and individuals as the Library of Alexandria, philosopher John Locke and George Washington.

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases, which launched in late March to support authors whose works have been overshadowed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, explores the history of alphabetical order, the woman behind Wolf Hall, the life of Malcolm X, secrets of urban design and chance’s role in shaping the world.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing-appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order by Judith Flanders

The invention of the alphabet dates to some 4,000 years ago, when merchants and mercenaries in Egypt’s Western Desert developed a phonetic system of symbols that could be rearranged into words. “Just as money was a stand-in for value,” notes Joe Moran in the Guardian’s review of A Place for Everything, “so the alphabet was a stand-in for meaning, separating words into letters for ease of reordering” and allowing humans “to shape whole universes of meaning out of a small number of letters.”

Derived from an array of earlier alphabetic systems, the Latin alphabet gained traction across the ancient world following its invention in the seventh century B.C. But a widely accepted alphabetical order remained elusive. As Chris Allnut points out for the Financial Times, Galen, the second-century A.D, Greek physician, took a subjective approach in his On the Properties of Food, organizing listings by general category and level of nourishment. The Library of Alexandria, meanwhile, used first-letter alphabetical order to organize certain scrolls, but “this was just one system among many,” according to Flanders. Later, medieval monks elevated the sacred over the profane; one European abbot wrote his English dictionary in descending order, beginning with angels, the sun and moon, and the Earth and the sea and concluding with weapons, metals and gems, per the Times’ Dan Jones.

The rise of the printing press in the mid-15th century furthered the cause of alphabetization by sparking an unprecedented explosion in the dissemination of information. Still, widespread adoption of alphabetical order didn’t simply follow “hard on the heels of printing,” according to Flanders. Instead, she writes, “[T]he reality was less tidy,” owing much to government bureaucracy, librarians and an array of fascinating historical figures.

A Place for Everything is peppered with tales of such individuals. Among others, the list of alphabetical order’s early proponents (or detractors) includes diarist Samuel Pepys; poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge; George Washington, who kept his records in an “alphabetted” ledger; and 13th-century Dominican monk John of Genoa, who prefaced his alphabetized Latin dictionary with a note stating, “I have devised this order at the cost of great effort and strenuous application. … I beg of you, therefore, good reader, do not scorn this great labor of mine and this order as something worthless.”

Mantel Pieces: Royal Bodies and Other Writing From the London Review of Books by Hilary Mantel

In March, Hilary Mantel concluded her much-lauded trilogy on statesman Thomas Cromwell with The Mirror & the Light, which follows the last four years of the Tudor minister’s life. Her next work—a collection of 20 essays previously published in the London Review of Books—expands the universe inhabited by Cromwell, deftly detailing Tudor figures like Anne Boleyn’s infamous sister-in-law, Jane; Henry VIII’s best friend, Charles Brandon; and 67-year-old noblewoman Margaret Pole, who was brutally executed on an increasingly paranoid Henry’s orders.

Mantel Pieces also moves beyond 16th-century England: “Royal Bodies,” a polarizing 2013 essay that employed Kate Middleton, Duchess of Cambridge, in its broader discussion of how the media, royal family and public treat female royals, appears, as do meditations on Madonna (the pop icon), the Madonna (or Virgin Mary), Britain’s “last witch” and a pair of 10-year-old’s headline-grabbing 1993 murder of 2-year-old James Bulger.

The author herself—the only two-time woman winner of the United Kingdom’s highest literary award, the Booker Prize—takes center stage in several personal essays. Tackling events including her first meeting with her stepfather, a showdown with a circus strongman and the aftermath of a major surgery, Mantel demonstrates that “[a]s a memoirist, [she] is without parallel,” per Frances Wilson of the Telegraph.

As Wilson concludes, “It is only when her essays are laid out like this that we can see the inside of Mantel’s huge head, bulging with knowledge and a million connections.”

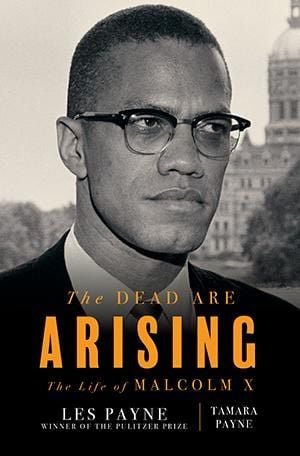

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les and Tamara Payne

When Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Les Payne died of a heart attack in 2018, his daughter, Tamara, stepped in to complete his unfinished biography of Malcolm X. Two years later, the 500-page tome is garnering an array of accolades, including a spot on the 2020 National Book Awards shortlist.

The elder Payne started researching the civil rights leader in 1990. Over the next 28 years, he conducted hundreds of interviews with Malcolm’s friends, family, acquaintances, allies and enemies, tirelessly working to tease out the truth behind what he described as the much-mythologized figure’s journey “from street criminal to devoted moralist and revolutionary.”

The Dead Are Arising traces Malcolm’s childhood in Nebraska, brushes with the law as a teenager in Michigan, time as a petty criminal in Boston and Harlem, emergence as a black nationalist leader of the Nation of Islam, and 1965 assassination. The result, writes Publishers Weekly in its review, is a “richly detailed account” that paints “an extraordinary and essential portrait of the man behind the icon.”

The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design by Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt

Based on the hit podcast “99% Invisible,” this illustrated field guide demystifies urban design, addressing “mysteries that most of us have never considered,” writes Kenneth T. Jackson for the New York Times. Why are manhole covers round? Why are revolving doors often sandwiched between traditional ones? What do the symbols painted on sidewalks and roads mean? And why are some public spaces so intentionally “hostile”?

Co-written by host Roman Mars and “99% Invisible” contributor Kurt Kohlstedt, The 99% Invisible City is “an ideal companion for city buffs, who’ll come away seeing the streets in an entirely different light,” according to Kirkus. Case studies range from metal fire escapes to fake facades, New York City’s Holland Tunnel, the CenturyLink Building in Minneapolis, modern elevators and utility codes, all of which are employed to illustrate broader points about inconspicuous and conspicuous design, geographic delineations versus designations, and the influence of government regulations on city landscapes, among other topics.

The authors’ enthusiasm for their subject is apparent in both the book’s wide-ranging scope and attention to detail. As Mars and Kohlstedt write in the introduction, “So much of the conversation about design centers on beauty, but the more fascinating stories of the built world are about problem-solving, historical constraints, and human drama.”

A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and You by Sean B. Carroll

Biologist Sean B. Carroll opens his latest book, A Series of Fortunate Events, with an anecdote about North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Il, who claimed to have scored five holes-in-one the very first time he played a round of golf. North Korea’s propensity for propaganda, coupled with the fact that golf champion Tiger Woods has scored just three holes-in-one in the entirety of his two-decade professional career, casts immediate doubts on Jong-Il’s account. But the scale of the lie is made all the more evident by Carroll’s employment of hard facts: As he points out, the chances of an amateur golfer achieving four holes-in-one are around 1 in 24 quadrillion—or 24 followed by 15 zeros.

In this case, the odds are against Jong-Il. But A Series of Fortunate Events demonstrates that similarly unlikely occurrences shape individual lives and the fate of the universe alike. “[B]reezy, anecdotal, informative and amusing,” notes the Wall Street Journal’s Andrew Crumey, Carroll’s work renders hefty topics accessible, exploring the perfect storm of events responsible for evolution, the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs and every living person’s conception. (In the scientist’s words, “it’s time to think about your parents’ gonads, and the moment you were conceived.”)

Acknowledging the “razor-thin line” between life and death or existence and extinction may seem like a terrifying prospect. But doing so can also be liberating.

“Look around you at all the beauty, complexity and variety of life,” writes Carroll. “We live in a world of mistakes, governed by chance.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)