Halloween Owes Its Tricks and Treats to the Ancient Celtic New Year’s Eve

During Samhain, the deceased came to Earth in search of food and comfort, while evil spirits, faeries and gods came in search of mischief

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/19/591971b9-174b-4308-918b-449c91fb1ce3/bonfire.jpg)

It’s that time of year again. The summer sun is becoming a distant memory, the days are growing shorter and cooler, the land is ripe for harvest—and the veil between the spirit world and the corporeal world has loosened, allowing the dead to mingle with the living.

Or so says ancient Celtic tradition. Samhain, pronounced sow-in, is the Celtic New Year’s Eve, which marks the end of the harvest. It served as the original Halloween before the church and the candy companies got their hands on it.

The Celts were an ancient group of people who lived more than 2,000 years ago in what is now Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Britain and much of Europe. They believed that there were two parts of the year: the light half and dark half. The holiday marked the beginning of the darkness and the time when the door between the living and the dead is at its weakest, says Brenda Malone, who works with the Irish Folklife division of the National Museum of Ireland.

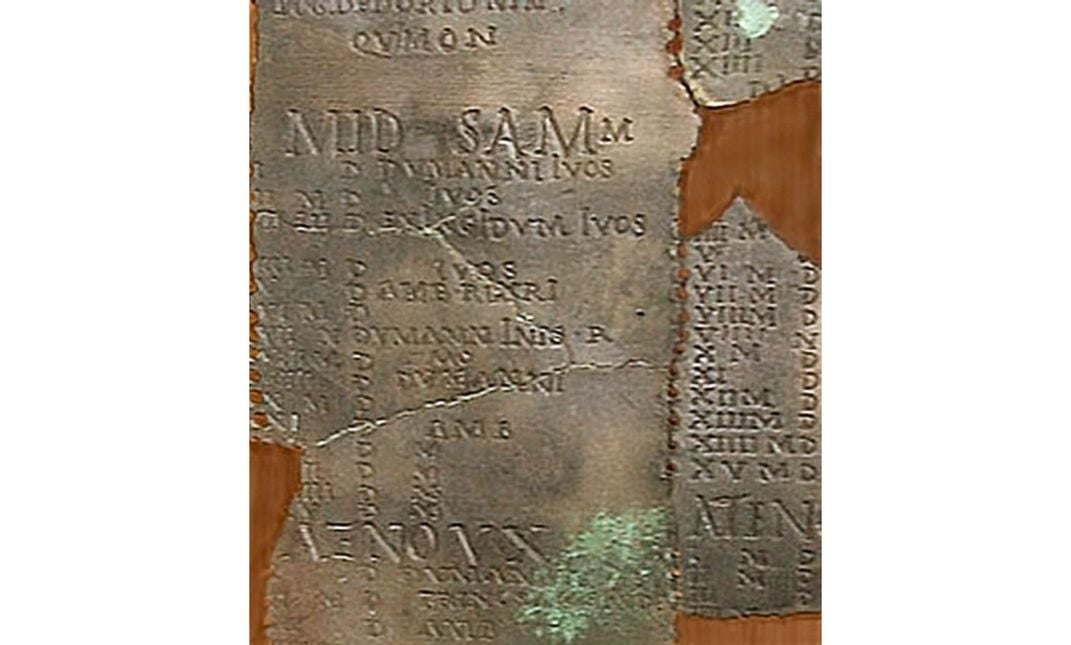

Seeing as there’s no historical evidence about what actually went on during early celebrations, the holiday is one of many legends. What historians do know is that the tradition of Samhain dates back centuries, and the first historical record of the holiday was engraved on a bronze calendar found in Coligny, France, in the 1st century B.C.E.

The holiday honors its namesake, Samhain, the lord of the dead or winter. Every winter, he became locked in a six-month struggle with Bael, the sun god. Every spring, Bael would win, marking a return to lightness, celebrated by Beltane or May Day. Though the people loved Bael, they also had affection for Samhain and honored the pagan god accordingly.

In medieval Ireland, the royal court at Tara would kick off celebrations by heading to the Hill of Tlachtga. There, the Druids, who served as Celtic priests, would start a ritual bonfire. The light called on people across Ireland to gather and build bonfires of their own. Around the bonfires, dancing and feasts took place as people celebrated the season of darkness.

But the bonfires of Samhain weren’t just a way to light up the chilly autumn night. Rather, they were also said to welcome the spirits that could travel to Earth during this special time. The deceased came in search of food and comfort, but evil spirits, faeries and gods also came in search of mischief. Among their ranks were witches, who didn’t just fly on their broomsticks, but also prowled the Earth on the backs of enormous cats (at least according to one account).

Some of the traditional stories of Samhain will sound familiar to Halloween revelers of today. People were said to disguise themselves as spirits to fool real ones, which apparently sometimes involved dressing up in animal skins and, in Scotland, wearing white and veiling or blackening one’s face.

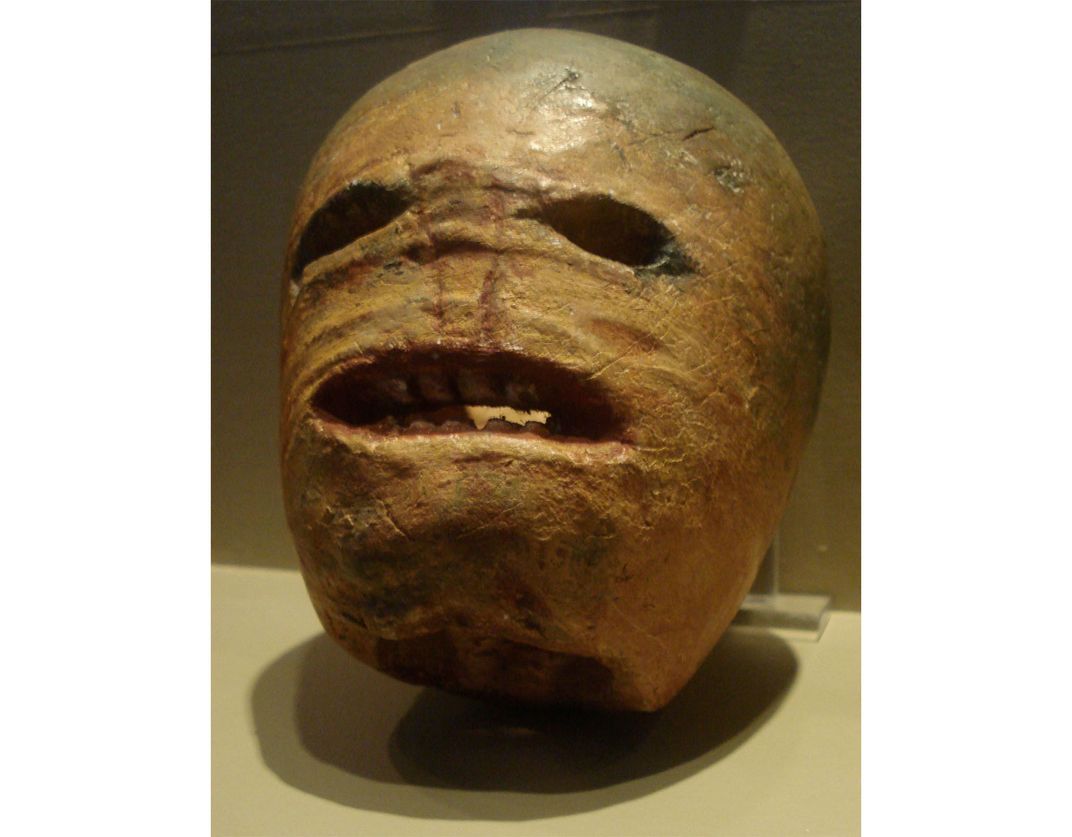

During Samhain, people were also said to carry treats in their pockets to give away as bribes, should they be caught unawares by wrathful spooks. They also held jack-o-lanterns—hollowed out turnips, potatoes, and beets (or skulls, if you believe some claims)—lit by candles to illuminate the night and scare away those seeking to cause them harm.

While there are many origin stories of the jack-o-lantern, a popular retelling focuses on a clever, drunkard by the name Stingy Jack who sold his soul to the devil, then tricked the devil out of the pact. As a consequence, when he died he could not enter heaven or hell and was forced instead to roam the Earth until Judgment Day. People knew when they saw Stingy Jack because he carried a carved up turnip with him that glowed with coal from hell that had been thrown at him by the devil. (Pumpkins would come into fashion much later on, when Irish immigrants in America found the gourds to be more plentiful and took to carving them to create jack-o-lanterns, instead.)

Since Samhain was the Celtic New Year’s Eve, perhaps it’s not surprising to find cleansing rituals woven into the fabric of the holiday. People took to walking between two bonfires with their cattle during Samhain because they believed the smoke and incense from burning herbs had special properties that would purify them. Likely, the smoke also served a practical purpose for cattle owners: It would have rid the beasts of fleas as they readied the livestock for winter quartering.

With the new year came new predictions for the future. Because the boundaries between the worlds were thought to be so thin, Samhain was the perfect time for telling fortunes and prophesying destinies. Many of these predictions were done with apples and nuts, which were fruits of the harvest. Apple bobbing and apple peeling were popular methods: For apple bobbing, the first person to bite into a fruit would be the first to marry. When it came to peeling, the longer a person’s apple skin could be unfurled without breaking, the longer they would live.

Some of the staple dishes served on Samhain in more modern times also speak to divination. To make Colcannon, a mashed potato dish that would have been introduced after potatoes were brought to Ireland from Peru, you craft a mixture of potatoe, cabbage, salt and pepper, into a mound and place a surprise, like a ring, thimble or button, inside it. Depending on what you discover in your food, a "destiny" is cast. Interpretations differ by area. Finding a ring in the dish could mean that you'll be married within the year, while a button might brand you a lifelong bachelor. Traditionally, tolkiens have also been placed in other foods, like barm bread cake, a sweet bread full of dried fruits, nuts and spice.

Back in 835 C.E., in an attempt to de-paganize Samhain the Roman Catholic Church turned November 1 into a holiday to honor saints, called All Saint’s Day. Later on, the church would add a second holiday, All Souls Day, on November 2, to honor the dead.

English rule steadily pushed paganism underground, even suppressing Celtic's native tongue, Gaelic, in Ireland, first in the area known as the Pale, and later with Brehon code throughout the rest of the country. But Samhain didn’t disappear. A modern version of the holiday is still celebrated with bonfires throughout Ireland. The holiday of Samhain is also practiced by modern Wiccans.

When immigrants brought their traditional practices across the Atlantic, the holiday took root in the United States, and mixed with the Roman holiday Pomona day and the Mexican Day of the Dead, it created the modern-day Halloween.

Though Samhain has enjoyed a lasting influence on mainstream culture, an important part of the celebration has been lost in the American version of the holiday. The opening of the barrier between worlds used to allow people to reflect on deceased loved ones. Though modern Halloween deals with graveyards and the walking dead, a focus on one’s own dearly departed is absent from the day.

Looking to add a bit of Samhain spirit to your Halloween this year? Consider leaving a loaf of bread on your kitchen table. A traditional Samhain practice, the gesture is intended to welcome back dead loved ones, says Malone. “They want to give something to them to show they've remembered them," she says. But don't worry if you don't have a loaf handy. Any offering of food that is considered special to the family will do.

Update: This post has been edited to clarify that the dish Colcannon would have been integrated into the holiday only after potatoes were brought to Ireland from Peru.