When George Washington Took a Road Trip to Unify the U.S.

Nathaniel Philbrick’s new book follows the first president on his 1789 journey across America

:focal(673x400:674x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1a/e5/1ae507db-f842-45e7-a024-0599d522b3d3/roadtrip.jpg)

In 1789, newly elected president George Washington faced one of the most difficult challenges of his life: creating a unified nation out of a disparate, discordant drove of 13 stubbornly independent former colonies.

To do that, Washington decided to take a road trip up and down the new United States. Along the way, the former commander-in-chief of the Continental Army used his prominence and prestige—as well as his peaceful persona and level leadership—to convince new Americans to forget what divided them and focus on what united them.

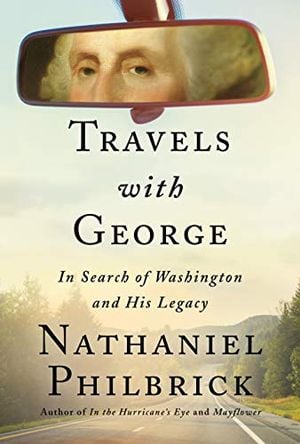

Award-winning author Nathaniel Philbrick revisits this historic journey in his new book, Travels With George: In Search of Washington and His Legacy. Drawing unnerving parallels to the nation’s current political landscape, the writer shows how the lessons taught by the “father of our country” are still relevant today.

Travels With George: In Search of Washington and His Legacy

Bestselling author Nathaniel Philbrick argues for Washington's unique contribution to the forging of America by retracing his journey as a new president through all thirteen former colonies, which were now an unsure nation.

“The divisions are remarkably reminiscent of where we are now,” says Philbrick. “It was a book that I thought would be fun to do but didn’t anticipate how deep I would get into it with my research and how it connects with modern events. Even though we were following someone from 230-plus years ago, it seemed like it was happening today.”

Part travelogue, part history lesson and part personal reflection, Travels With George reveals how Washington convinced a very skeptical public that America could pull off its experiment in democracy. The key, the president argued, was in the hands of those who elected him: “The basis of our political system is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government.”

“This was a novel concept,” Philbrick says. “Everywhere else, there is a king or dictator who is leading the country. This is not someone who has inherited the role. This is someone who has been elected by the people. It had never been done before.”

The leading issue of the day was who should have control: the states or the federal government. Since 1781, the new country had foundered along under the Articles of Confederation, which provided extensive power to the states. It wasn’t working. The Federalists wanted a stronger central government, while the Anti-Federalists wanted power to remain with the former colonies.

Written in 1787, the Constitution sought to remedy the problem by divvying up responsibilities in a more sensible manner—but it only created a deeper divide between the two parties. Washington, who had a disdain for political parties and famously refused to join one, hoped to show Americans a middle ground. He decided to use his star power to reassure the nation with his calm, steady influence.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/50/b3/50b3187b-f2dd-413e-850e-4665fb450179/nmah-2006-7431.jpeg)

“Men’s minds are as variant as their faces,” wrote Washington in a 1789 letter. “Liberality and charity … ought to govern in all disputes about matters of importance.” The president added that “clamor and misrepresentation … only serve to foment the passions, without enlightening the understanding.”

Washington took his show on the road in the spring of 1789. Over the span of two years, he visited all 13 original states (14 if you count Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts), traveling on horseback and by carriage along rutted dirt roads and over rising rivers. The president often donned his magnificent Continental Army uniform and rode his favorite white stallion into towns, where he was greeted by cheering citizens. Along the way, he communicated his hopes for the new nation and how he needed everyone’s support to make this vision reality.

“It was awe inspiring,” Philbrick says. “Washington was seriously the only one [who] could have sold the concept to the people. Not only was [he] able to unify us politically, he was able to unify us as a nation. Instead of saying our state is our country—as was customary back then—we were saying the United States is our nation. We take that for granted today, but it wasn’t that way when Washington took office in 1789.”

To help Americans understand the importance of uniting, Washington imparted some not-too-subtle lessons. First, he refused to travel to Rhode Island until the state officially ratified the Constitution in May 1790. Once residents accepted the measure, Washington quickly added the new country’s smallest state to his itinerary. He was greeted by cheering citizens, Federalist and Anti-Federalist alike.

“His decision to visit Newport and Providence just a few months after Rhode Island approved the Constitution caught just about everybody by surprise,” Philbrick says. “It was an inspired move, turning some of the new government’s harshest critics into some of its biggest fans.”

He adds, “Washington was bigger than Elvis. He was the most popular man in the world at the time.”

In Boston, the president made a profound statement by refusing John Hancock’s invitation to dinner. The Massachusetts governor had failed to visit Washington following his arrival in town, instead expecting the president to come to him.

“Before the ratification of the Constitution, the states held most of the power,” Philbrick explains. “Washington wanted to make it unmistakably clear that things were different now and that the president outranked a governor. The distinction seems almost laughably obvious today, but that was not the case in the fall of 1789.”

In the South, Washington similarly demonstrated his leadership skills by announcing the formation of a new federal district that would serve as the nation’s seat of power. Known as the Residence Act, this 1790 compromise moved the capital from New York to its present-day location. (Philadelphia served as the temporary capital during Washington, D.C.’s construction.) In return, the federal government assumed state debts accrued during the Revolutionary War.

“The real culminating moment for me came at the end of Washington’s tour of the South, when he finalized the deal to build the new capital city on the banks of the Potomac,” Philbrick says. “For him, the creation of what would become Washington, D.C. was the physical embodiment of the lasting union he was attempting to establish during his tour of America.”

Washington was clearly proud of completing this arduous, 1,700-mile cross-country journey. It was a major accomplishment to undertake—and survive—such a trip when most roads were little more than bumpy paths through the wilderness.

The president also had reason to be pleased with his reception. Greeted by throngs of exuberant people everywhere, Washington was, on several occasions, moved to tears by the veneration he received. His tour to gain “the good-will, the support, of the people for the General Government,” as he later wrote, clearly united Americans in putting aside their differences for the future prosperity of the country.

In the spirit of John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley: In Search of America, which found that author traversing the country with his dog, Philbrick and his wife, Melissa, brought their pup Dora on their 2018–19 journey across the eastern part of the country. As much as possible, they followed Washington’s original route, traveling by ship to Rhode Island and along the Post Road in Connecticut. The modern-day trio was slowed by traffic jams at the shopping malls that now proliferate the historic highway.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/11/99115d90-b40a-4435-b2ea-bf32baccb2e0/npg-npg_2001_13.jpeg)

Travels With George is interspersed with interactions of people the Philbricks met, including Miguel in Bristol, Pennsylvania, and Kassidy Plyler in Camden, South Carolina. Each provides their own unique perspective on being an American: Miguel reflects on his life after moving to the U.S. from Puerto Rico in 1968, while Kassidy relays her experience of being a member of the Catawba Nation, which allied with Washington during the Seven Years War and the American Revolution.

So, is Washington still relevant to Americans today? More so than ever, Philbrick says.

“Washington was the biggest guy on the planet at the time,” he adds. “What he wanted to do was create something that was bigger than he was. That’s the important legacy that we must honor. It’s up to us to make sure it isn’t lost.”

Would the “father of our country” be upset by the separation so evident in society today? Philbrick pauses for a moment, then answers:

I don’t think Washington would be that surprised. By the time he was done with his second term as president, the political divide was as wide as it is today. I think he would have been really upset at the attempts to undermine the people’s faith in government and the rule of law. Those were the essential elements in this whole experiment we call the United States. The people have to have faith in the laws of the land. To undermine that faith is to undermine Washington’s legacy. It’s up to each generation of Americans to reaffirm the legacy of what Washington created.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)