The Feminist History of ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’

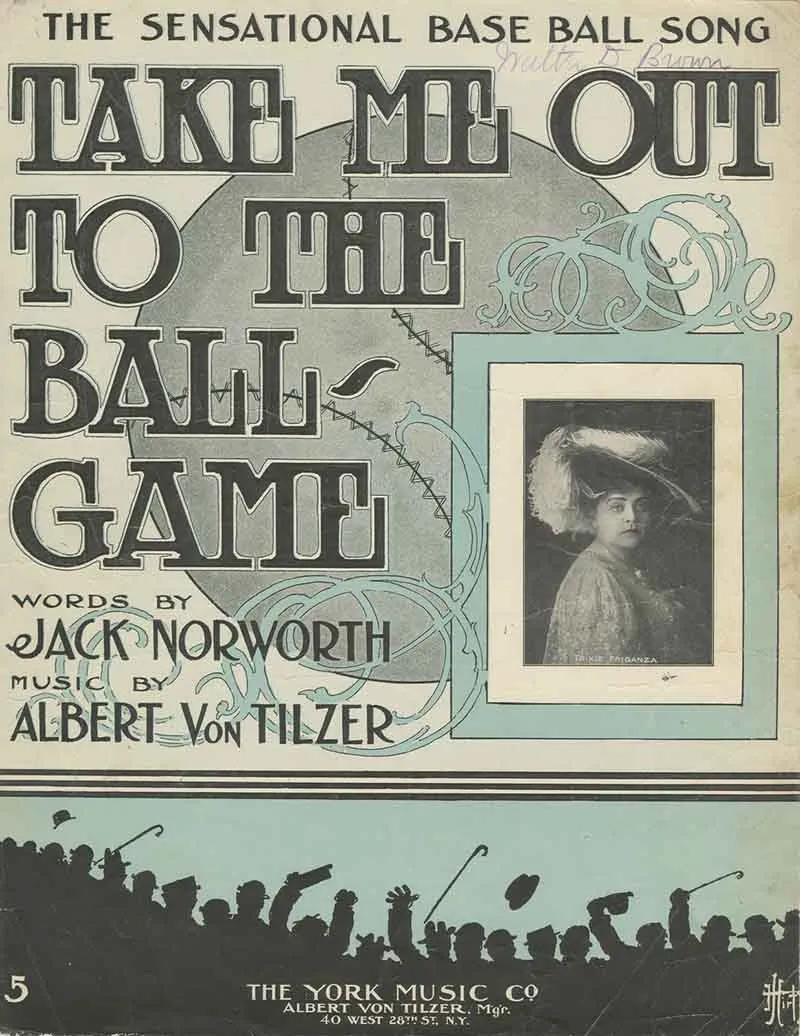

Trixie Friganza, an actress and suffragist, inspired the popular song of the seventh inning stretch

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/71/b371b9bc-7956-4eb6-a56a-d3f442fd4c71/trixie_friganza.jpg)

Described by Hall of Fame broadcaster Harry Caray as "a song that reflects the charisma of baseball,” ”Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” written in 1908 by lyricist Jack Norworth and composer Albert von Tilzer, is inextricably linked to America’s national pastime. But while most Americans can sing along as baseball fans “root, root, root for the home team,” few know the song’s feminist history.

A little more than a decade ago, George Boziwick, historian and former chief of the music division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, uncovered the hidden history behind the tune: the song was written as Jack Norworth’s ode to his girlfriend, the progressive and outspoken Trixie Friganza, a famous vaudeville actress and suffragist.

Born in Grenola, Kansas, in 1870, Friganza was a vaudeville star by the age of 19, and her life was defined by her impact both on and off the stage. As a well-known comedic actress, Friganza was best known for playing larger-than-life characters, including Caroline Vokes in The Orchid and Mrs. Radcliffe in The Sweetest Girl in Paris. Off the stage, she was an influential and prominent suffragist who advocated for women’s social and political equality. The early 1900s were a critical time in the fight for the vote: members of the Women’s Progressive Suffrage Union held the first suffrage march in the United States in New York City in 1908, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in 1909 to fight for voting rights of people of color, and in 1910, 10,000 people gathered in New York City’s Union Square for what was then the largest demonstration in support of women’s suffrage in American history.

Friganza, an unflinching supporter in the fight for the ballot, was a vital presence in a movement that needed to draw young, dynamic women into the cause. She attended rallies in support of women’s right to vote, gave speeches to gathering crowds, and donated generously to suffrage organizations. “I do not believe any man – at least no man I know – is better fitted to form a political opinion than I am,” Friganza declared at a suffrage rally in New York City in 1908.

Listen to this episode of the Smithsonian's podcast "Sidedoor" about the history of 'Take Me Out to the Ballgame"

“Trixie was one of the major suffragists,” says Susan Clermont, senior music specialist at the Library of Congress. “She was one of those women with her banner and her hat and her white dress, and she was a real force to be reckoned with for women’s rights.” In 1907, Friganza’s two worlds—celebrity and activism—would collide when she began a romantic relationship with Jack Norworth.

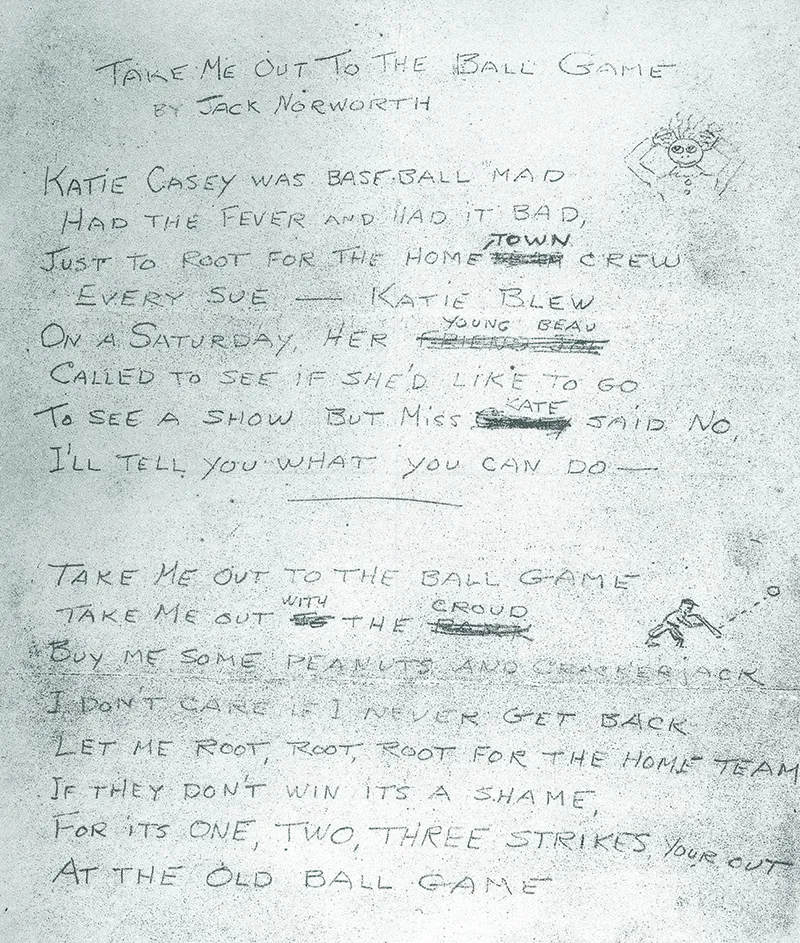

Norworth, a well-known vaudeville performer and songwriter in his own right, was married to actress Louise Dresser when he met Friganza. (When news of the wedded couple’s separation hit the press, Dresser announced that her husband was leaving her for the rival vaudeville star.) The affair was at its peak in 1908 when Norworth, riding the subway alone on an early spring day through New York City, noticed a sign that read “Baseball Today—Polo Grounds” and hastily wrote the lyrics of what would become “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” on the back of an envelope. Today, those original lyrics, complete with Norworth’s annotations, are on display at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Norworth, realizing that what he had written was “pretty good,” took the lyrics to friend, collaborator and composer Albert von Tilzer. The pair knew that more songs had been written about baseball than any other sport in the U.S.—by 1908, hundreds of songs about the game had been published, including “The Baseball Polka” and “I’ve Been Making a Grandstand Play for You.” But they also knew that no single song about the sport had ever managed to capture the national imagination. So although neither Norworth nor von Tilzer had ever attended a baseball game, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office on May 2, 1908.

While most Americans today recognize the chorus of "Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” it is the two additional, essentially unknown verses that reveal the song as a feminist anthem.

Katie Casey was baseball mad,

Had the fever and had it bad.

Just to root for the home town crew,

Ev’ry sou Katie blew.

On a Saturday her young beau

Called to see if she’d like to go

To see a show, but Miss Kate said “No,

I’ll tell you what you can do:

Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd;

Just buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack,

I don’t care if I never get back.

Let me root, root, root for the home team,

If they don’t win, it’s a shame.

For it’s one, two, three strikes, you’re out,

At the old ball game.

Katie Casey saw all the games,

Knew the players by their first names.

Told the umpire he was wrong,

All along,

Good and strong.

When the score was just two to two,

Katie Casey knew what to do,

Just to cheer up the boys she knew,

She made the gang sing this song:

Take me out to the ball game….

Featuring a woman named Katie Casey who was “baseball mad,” who “saw all the games” and who “knew the players by their first names,” “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” tells the story of a woman operating and existing in what is traditionally a man’s space—the baseball stadium. Katie Casey was knowledgeable about the sport, she was argumentative with the umpires, and she was standing, not sitting, in the front row. She was the “New Woman” of the early 20th Century: empowered, engaged, and living in the world, uninhibited and full of passion. She was, historians now believe, Trixie Friganza.

“[Norworth] was with [Friganza] at the time he wrote this song,” says Clermont. “This is a very progressive woman he’s dating, and this is a very progressive Katie Casey. And [Friganza] very likely was the influence for ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”

As further evidence that the fictional Katie Casey was based on Friganza, historians from Major League Baseball and the Library of Congress point to the covers of two original editions of the sheet music, which feature Friganza. “I contend the Norworth song was all about Trixie,” Boziwick told the New York Times in 2012. “None of the other baseball songs that came out around that time have the message of inclusion… and of a woman’s acceptability as part of the rooting crowd.” Boziwick’s discovery of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game’s” feminist history, coming nearly 100 years after the song’s publication, shows how women’s stories are so often forgotten, overlooked and untold, and reveals the power of one historian’s curiosity to investigate.

And while “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” has endured as one of the most popular songs in America over the century (due in no small part to announcer Harry Caray’s tradition, started in 1977, of leading White Sox fans in the chorus of the song during the 7th inning stretch), Friganza and Norworth’s romance ended long before the song became a regular feature in baseball stadiums across the U.S. Although Norworth’s divorce from Dresser, was finalized on June 15, 1908, just one month after the publication of the song, Norworth married his Ziegfeld Follies costar Nora Bayes, not Trixie Friganza, the following week.

The news came as a surprise to both tabloid readers and Friganza, but, not one to be relegated to the sidelines, she went on to star in over 20 films, marry twice and advocate for the rights of women and children. So, this postseason, enjoy some peanuts and Cracker Jacks and sing a round of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” for Trixie Friganza, Katie Casey and the bold women who committed their lives to fight for the ballot.

This piece was published in collaboration with the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission, established by Congress to commemorate the 2020 centennial of the 19th Amendment and women’s right to vote.