Fate of the Cave Bear

The lumbering beasts coexisted with the first humans for tens of thousands of years and then died off. Why?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cave-Bears-Chauvet-painting-631.jpg)

Hervé Bocherens says his colleagues find his research methods a little "crude." He dissolves 30,000-year-old animal bones in hydrochloric acid strong enough to burn through metal, soaks the bone solution in lye, cooks it at about 200 degrees Fahrenheit and freeze-dries it until what's left is a speck of powder weighing less than one one-hundredth of an ounce. The method may be harsh, but the yield is precious—the chemical biography of a cave bear.

Bocherens, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Tübingen, Germany, is in the vanguard of research on the bear, a European species that died out 25,000 years ago. People have been excavating cave bear remains for hundreds of years—in the Middle Ages, the massive skulls were attributed to dragons—but the past decade has seen a burst of discoveries about how the bears lived and why they went extinct. An abundance of bear bones has been found from Spain to Romania in caves where the animals once hibernated. "Caves are good places to preserve bones, and cave bears had the good sense to die there," Bocherens says.

Along with mammoths, lions and woolly rhinos, cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) were once among Europe's most impressive creatures. Males weighed up to 1,500 pounds, 50 percent more than the largest modern grizzlies. Cave bears had wider heads than today's bears, and powerful shoulders and forelimbs.

Prehistoric humans painted images of the animals on cave walls and carved their likeness in fragments of mammoth tusk. But the relationship between humans and cave bears has been mysterious. Were humans prey for the bears, or predators? Were bears objects of worship or fear?

Cave bears evolved in Europe more than 100,000 years ago. Initially they shared the continent with Neanderthals. For a time, archaeologists thought Neanderthals worshiped the bears, or even shared caves with them. The idea was popularized by Jean Auel's 1980 novel, The Clan of the Cave Bear, but has since been rejected by researchers.

Modern humans arrived in Europe about 40,000 years ago and were soon aware of the bears. The walls of France's Chauvet cave, occupied 32,000 years ago, are painted with lions, hyenas and bears—perhaps the oldest paintings in the world.

The artists weren't the cave's only occupants: the floor is covered with 150 cave bear skeletons, and its soft clay still holds paw prints as well as indentations where bears apparently slept. Most dramatically, a cave bear skull was perched on a stone slab in the center of one chamber, placed deliberately by some long-gone cave inhabitant with opposable thumbs. "There's no way to tell if it was just curiosity that made someone put a skull on the rock or if it had religious significance," says Bocherens.

Another discovery, hundreds of miles to the east of Chauvet, would shed light on the relationship between cave bears and humans.

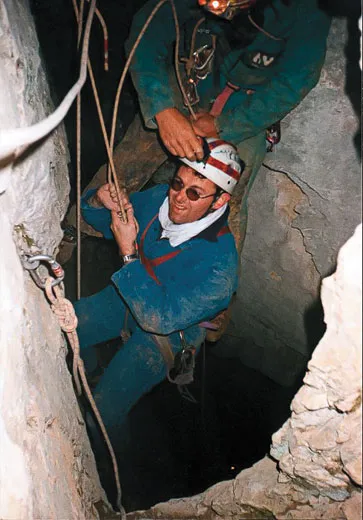

The Swabian Jura is a limestone plateau in southwestern Germany that is riddled with caves. A short walk from the village of Schelklingen takes visitors to the foot of a limestone cliff in the Ach Valley. A steel gate guards the Hohle Fels cave from vandals and curiosity-seekers. Inside, the sound of dripping water competes with the quiet conversation of a half-dozen archaeologists.

Floodlights in the cave's main chamber illuminate the ceiling, vaulted like a cathedral above 5,000 square feet of floor space. Long ago, as shown by the bones and tools that archaeologists have found, cave bears and human beings sought shelter here from winter weather.

In 2000, University of Tübingen paleobiologist Susanne Münzel unearthed a bear vertebra with a tiny triangular piece of flint embedded in it. The stone was likely a broken spear point, hard evidence of a successful bear hunt 29,000 years ago.

Münzel also found bear bones that had clearly been scratched and scraped by stone tools. Cut marks on skulls and leg bones showed that the bears had been skinned and their flesh cut away. "There must have been cave bear hunting, otherwise you wouldn't find meat cut off the bone," she says. Many of the bones were from baby bears, perhaps caught while hibernating.

Cave bears disappeared not long after humans spread throughout Europe. Could hunting have led to the bears' extinction? That's not likely, according to Washington University at St. Louis anthropologist Erik Trinkaus. "People living in the late Pleistocene weren't stupid," he says. "They spent an awful lot of time avoiding being eaten, and one of the ways to do that is to stay away from big bears." If hunting was an isolated event, as he argues, there must be another reason the bears died out.

Hervé Bocherens' test tubes may hold the clues. Running his white powder through a mass spectrometer, he identifies different isotopes, or chemical forms, of elements such as carbon and nitrogen that reflect what the bears were eating and how quickly they grew. After studying hundreds of bones from dozens of sites in Europe, Bocherens has found that cave bears mainly ate plants.

That would have made the bears particularly vulnerable to the last ice age, which began around 30,000 years ago. The prolonged cold period shortened or eliminated growing seasons and changed the distributions of plant species across Europe. Cave bears began to move from their old territories, according to a DNA analysis led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig of teeth found near the Danube River. The cave bear population there was relatively stable for perhaps 100,000 years, with the same genetic patterns showing up generation after generation. But about 28,000 years ago, newcomers with different DNA patterns arrived—a possible sign of hungry bears suddenly on the move.

But climate change can't be solely to blame for the bears' extinction. According to the latest DNA study, a Max Planck Institute collaboration including Bocherens, Münzel and Trinkaus, cave bear populations began a long, slow decline 50,000 years ago—well before the last ice age began.

The new study does support a different explanation for the cave bear's demise. As cavemen—Neanderthals and then a growing population of modern humans—moved into the caves of Europe, cave bears had fewer safe places to hibernate. An acute housing shortage may have been the final blow for these magnificent beasts.

Andrew Curry writes frequently about archaeology and history for Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)