On a narrow street in Damascus, one of the oldest cities in the world, I pull open a heavy iron door in a cinderblock wall and enter an ancient synagogue. Behind the door, just past a tiled courtyard shaded by a large tree, I am stunned by what I see.

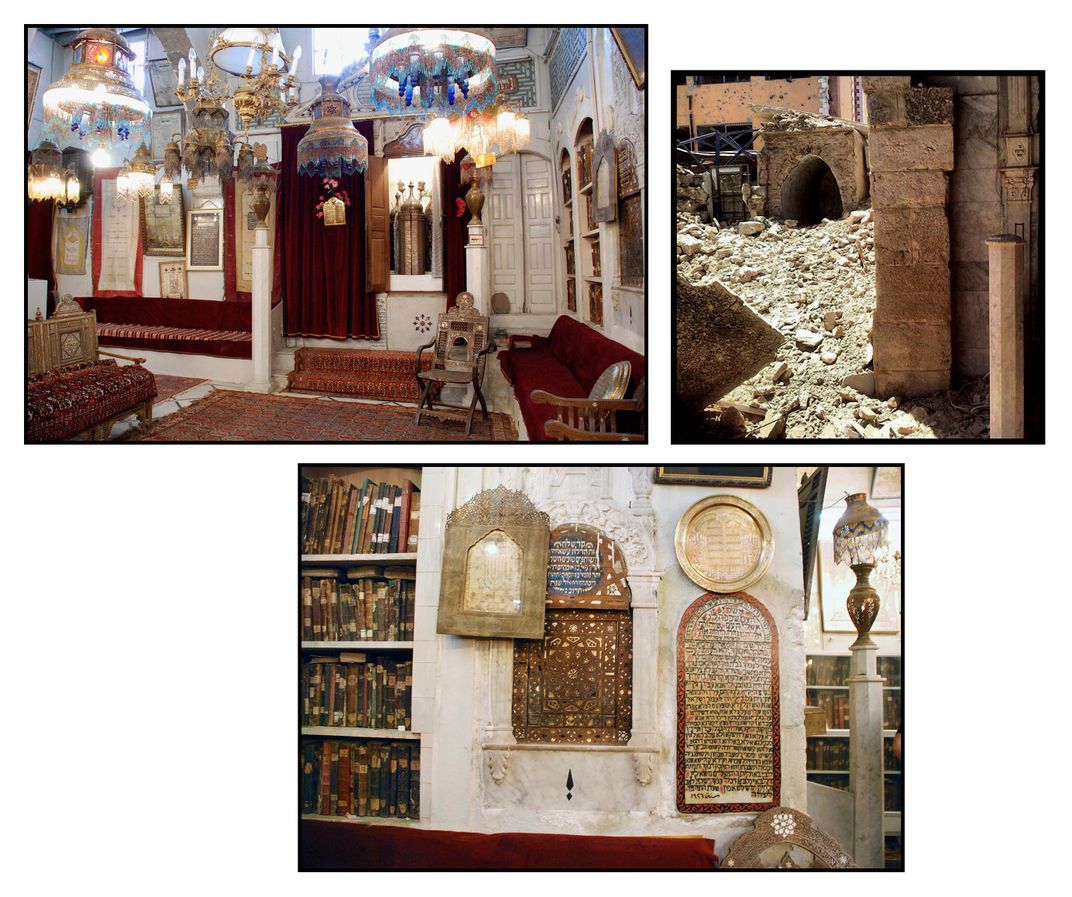

I’m standing inside a jewel box. The small room is illuminated by dozens of elaborate beaded chandeliers; its walls are covered with thick red velvet draperies, its stone floor with richly patterned carpets. In front of me is a large flat stone topped with a golden menorah: Here, an inscription informs me, the Hebrew prophet Elijah anointed his successor Elisha, as described in the biblical Book of Kings.

For a place that drew Jewish pilgrims for centuries, it is remarkably well preserved—and startlingly intimate. There are no “pews” here; instead, there are low cushioned couches facing each other, as though this were a sacred living room. A raised marble platform in the center has a draped table for public Torah readings; at the room’s far end is an ornate wooden cabinet filled with ancient Torah scrolls, their parchments concealed inside magnificent silver cases. On the walls are framed Hebrew inscriptions, featuring the same prayers my son is currently mastering for his bar mitzvah in New Jersey.

I should mention here that I’ve never been to Damascus. Also, this synagogue no longer exists.

I’m using a virtual platform called Diarna, a Judeo-Arabic word meaning “our homes.” The flagship project of the nonprofit group Digital Heritage Mapping, Diarna is a vast online resource that combines traditional and high-tech photography, satellite imaging, digital mapping, 3-D modeling, archival materials and oral histories to allow anyone to “visit” Jewish heritage sites throughout the Middle East, North Africa and other places around the globe.

The idea of taking online tours isn’t so novel these days, now that the coronavirus pandemic has shifted so much tourism online. But Diarna is no gee-whiz virtual playground. The places it documents are often threatened by political instability, economic hardship, authoritarianism and intolerance—and in many cases, Diarna’s virtual records are all that stand between these centuries-old treasures and total oblivion.

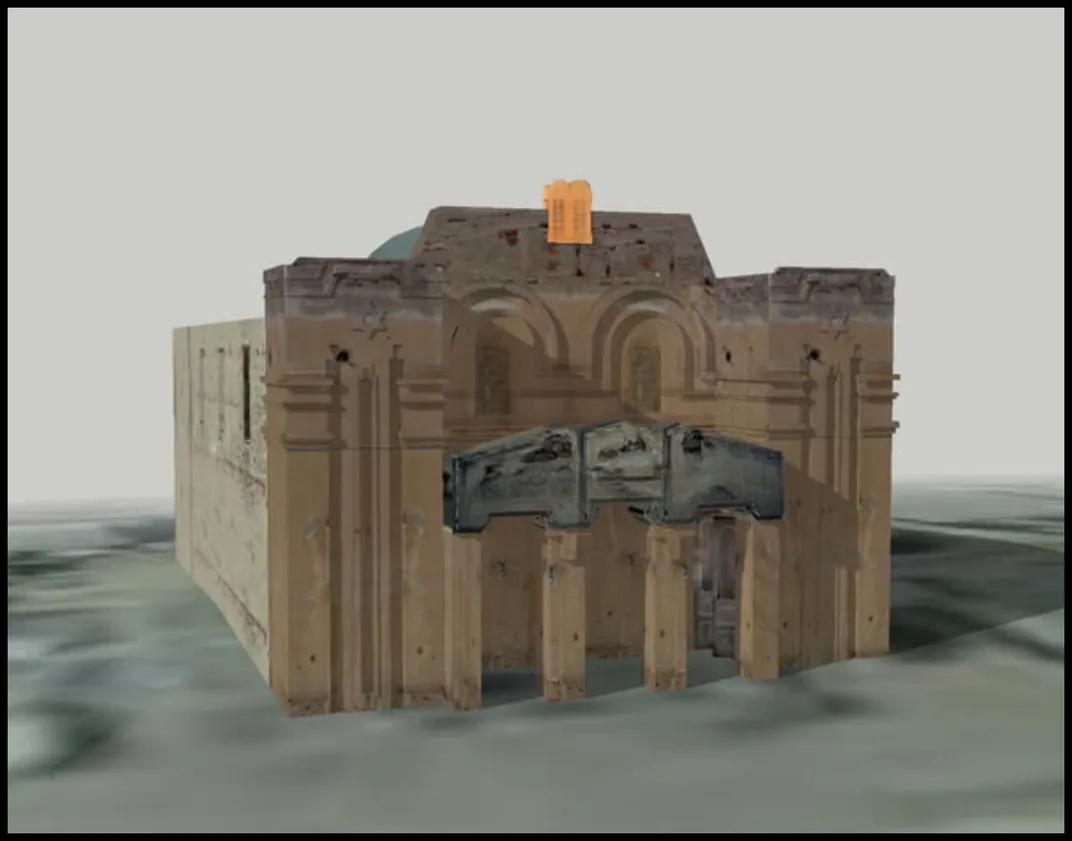

That synagogue I visited, the Eliyahu Hanavi-Jobar Synagogue in Damascus, was documented by one of Diarna’s photographers before 2014, when Syria’s civil war transformed the 500-year-old site to rubble—photos of which you can also find on Diarna. The implications of this project are enormous, not only for threatened Middle Eastern minorities, but for all of us. It has the power to change the very nature of how we understand the past.

Diarna is the brainchild of Jason Guberman-Pfeffer, then a recent graduate of Sacred Heart University active in Middle Eastern human rights circles, and Fran Malino, then a Wellesley College professor studying North African Jewish history. In 2008, a mutual acquaintance of theirs traveled to Morocco to explore his wife’s family’s Moroccan-Jewish roots, and he found that many of the places he visited—synagogues, schools and cemeteries—were startlingly decayed. And the elderly people who remembered the places best were dying off. Malino and Guberman-Pfeffer put their heads together and realized their untapped power: By combining their archival skills, their contacts in the region and newly available technologies like Google Earth, they could preserve these places forever.

“It morphed almost immediately into this huge project,” remembers Malino, who is now Diarna’s board president and the head of its nonprofit parent company, Digital Heritage Mapping. Malino began by recruiting among her own students, but was soon startled by how many young people—including American photographers and budding scholars, and also people on the ground in North Africa—signed on. “In very short order with a very small budget, we had a number of people working for us so we could set up a website and accumulate a lot of information and photos.”

More than a decade later, with Guberman-Pfeffer as its project coordinator, Diarna has run over 60 field expeditions, sending photographers and researchers to collect information and visual evidence of the remains of Jewish communities, and the organization has now documented nearly 3,000 sites throughout the Middle East and North Africa, as well as elsewhere in the world. Starting with an interactive map of the world, anyone can zoom in and explore them all. Some of these locations include little more than a town’s name and basic information about its Jewish history, with research still in progress.

But many include beautiful photography showing physical sites from many angles, bibliographies of historical resources, and oral histories from former Jewish residents describing lives lived in these places. Other sites are being documented in ways unimaginable even just a few years ago. Today, Diarna’s photographers, researchers and volunteers are using tools like a portable 360-degree camera that creates a fully immersive view of a building’s interior, drone photography for bird’s-eye views of ancient ruins, and design software that can turn traditional photography into vivid 3-D models.

Social media has also made it possible, even easy, to collect amateur photos and videos of places otherwise inaccessible, and to locate those who once lived in these Jewish communities. Diarna’s interactive map often includes links to these amateur videos and photos when no others exist, giving people a window on sites that are otherwise invisible.

And as former Jewish residents of these places age beyond memory’s reach, Diarna’s researchers are conducting as many in-person interviews with such people as they can, creating a large backlog in editing and translating these interviews to make them accessible to the public. The oral histories currently available on the site are a tiny fraction of those Diarna has recorded and will eventually post. “We’re in a race against time to put these sites on the map,” Guberman-Pfeffer says, “and to preserve these stories before they’re forever lost.”

* * *

I’ve been thinking about time and loss since I was 6 years old, when it first dawned on me that people who die do not ever return—and this was also true for each day I’d ever lived. As a child I would often get into bed at night and wonder: The day that just happened is gone now. Where did it go? My obsession with this question turned me into a novelist, chasing the possibility of capturing those vanished days. Inevitably these efforts fail, though I stupidly keep trying.

When I first learned about Diarna, I was a bit alarmed to discover an entire group of people who not only share my obsession but are entirely undeterred by the relentlessness of time and mortality—as if a crowd of chipper, sane people had barged into my private psych ward. The bright, almost surreal hope that drives Diarna is the idea that, with the latest technology, those lost times and places really can be rescued, at least virtually, from oblivion. It’s a little hard to believe.

Jews have lived throughout the Middle East and North Africa for thousands of years, often in communities that long predated Islam. But in the mid-20th century, suspicion and violence toward Jews intensified in Arab lands. Nearly a million Jews emigrated from those places. In some instances, like Morocco, the Jewish community’s flight was largely voluntary, driven partly by sporadic anti-Jewish violence but mostly by poverty and fear of regime change. At the other extreme were countries like Iraq, where Jews were stripped of their citizenship and had their assets seized. In Baghdad, a 1941 pogrom left nearly 200 Jews dead and hundreds of Jewish-owned homes and businesses looted or destroyed.

Today, people and governments have varying attitudes toward the Jewish communities that once called these countries home. Morocco publicly honors its Jewish history; there, the government has supported Jewish site maintenance, and Diarna cooperates with a nonprofit called Mimouna, a group devoted to documenting Jewish life. In other places, there is public denigration or even denial of a Jewish past. In Saudi Arabia, decades of pan-Arabist and Islamist propaganda have left the public ignorant that Jews still lived in the kingdom after the Islamic conquest, despite recent official efforts to recognize the kingdom’s remarkable Jewish historical sites. Diarna researchers have been making plans to travel to Saudi Arabia to explore ruins of once-powerful ancient Jewish cities.

In some places, abandoned synagogues have been transformed into mosques; in others, tombs of Jewish religious figures or other sacred spaces are still being maintained, or even revered, by non-Jewish locals. More often, especially in poor rural areas where land is worth little and demolition costs money, abandoned Jewish sites are simply left to decay. Many, many photos on Diarna show derelict cemeteries with toppled gravestones, synagogues with the second story and roof caved in, holy places in the process of returning to dust.

Diarna is officially apolitical, refusing to draw conclusions about any of this—which for a novelist like me is maddening. I want the past to be a story, to mean something. So do lots of other people, it turns out, from Zionists to Islamic fundamentalists. Guberman-Pfeffer politely declines to engage. “It’s not our job to give a reason why this particular village doesn’t have Jews anymore,” he tells me. “We just present the sites.” Malino, as a historian, is even more rigorous in defending Diarna’s neutral approach. “In my mind the goal is to make available to all of us, whether they’re in ruins or not, the richness of those sites, and to preserve the wherewithal of accessing that information for the next generation. We are not taking a political position, not trying to make a statement. Absolutely not.”

Every Diarna researcher I talked to stood firm on this point. But the choice to present these Jewish sites is itself a statement, one that underscores an undeniable reality. “The Middle East is becoming more homogeneous,” says Diarna’s lead research coordinator, Eddie Ashkenazie, himself a descendant of Syrian Jews. “We’re pointing out that the store next to your grandfather’s in the market was once owned by the Cohen family,” he tells me. “Whether they got along or it was fraught with tension is going to vary depending on the time and place, but it testifies to a society that had other voices in it, that had minorities in it, that was heterogeneous. Today you have whole societies that are only Libyan Muslims, or only Shiite Arabs. But they used to be incredibly diverse. All Diarna is trying to do is say that Jews once lived here.”

* * *

“We are rewriting the history books,” Ashkenazie says, and then corrects himself: “Not rewriting; we’re just writing this history, period. Because no one else has yet.”

Over the phone, Ashkenazie walks me through an elaborate PowerPoint presentation that spells out exactly how Diarna does its current work. He tells me about the Libyan town of Msellata, where a former Jewish resident, interviewed by one of Diarna’s researchers, mentioned that the synagogue was once located “near the police station.” On-screen, Ashkenazie shows me how he used the mapping tool Wikimapia to find the town’s police station and calculate a walking-distance radius around it.

Next came diligence plus luck: While he was scouring Libyan social media, he came across an archival photo that a current Msellata resident happened to post on Facebook, which clearly showed the synagogue across the street from a mosque. Ashkenazie then identified the still-standing mosque from satellite photos, thereby confirming the synagogue’s former location. “What you don’t see are the hours of interviews before we got to the guy who mentioned the police station,” Ashkenazie says. “It’s the work of ants. It’s very tedious, but it works.”

I find myself wondering what moves people to do this “work of ants.” My own great-grandparents, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe at the turn of the last century, wanted at all costs to forget the “old country”; this was true for many Middle Eastern Jewish refugees as well, especially those with bitter memories of societies that turned on them. Ashkenazie admits that many of Diarna’s interviewees—mostly elderly Israelis—are baffled as to why anyone would care about the street corner where their synagogue once stood, and they have to be convinced to sit down with his researchers.

The disappearance of these communities is, in fact, just an acute (and sometimes violent) version of what eventually happens to every community, everywhere. All of us will die; all of our memories will be lost. Today it’s a synagogue in Tunisia that’s crumbling; eventually the sun will explode. Why even try?

These questions haunt me as I sift through Diarna’s site, along with several unedited interviews that Ashkenazie shared with me: a man describing Yom Kippur in rural Yemen, a woman detailing the Tomb of Ezra in Iraq, a man recalling the Hebrew textbooks he studied in Cairo. The speakers in these videos are deeply foreign to me, elderly people with Arabic accents describing daily lives I can barely imagine. Yet they often mention things I recognize: a holiday, a biblical figure, a prayer, a song.

“There is a deeply pluralistic religious and cultural history in Iraq. We’ve offered training and assistance to Iraqi colleagues as they document parts of Iraq’s diverse past , such as the Jewish quarters of the old cities.”

—Katharyn Hanson, Secretary's Scholar, Smithsonian's Museum Conservation Institute

It occurs to me that Jewish tradition, like every tradition, is designed to protect against oblivion, capturing ancient experiences in ritual and story and passing them between generations. Diarna is simply a higher-tech version of what everyone’s ancestors once did—pass along memories around a fire—but with new technologies expanding that warm, bright circle.

In one video interview, not yet online, an elderly man speaks in Arabic-accented Hebrew about his hometown of Yefren in Libya. Up the hill from his family’s branch-ceilinged stone house, he says, was the tiny town’s 800-year-old synagogue and adjoining ritual bath. As he sits with a Diarna researcher at his kitchen table in Israel, he scribbles maps and floor plans, describing the synagogue with its interior arches, its columns, its holy ark for Torah scrolls. Listening to this man’s rambling voice is like hearing someone recount the elaborate details of a dream.

Which is why it is utterly unnerving to click on the town of Yefren on Diarna’s interactive map and find a recent YouTube clip by a traveler who enters the actual physical ruins of that very synagogue. The building is a crumbling wreck, but its design is exactly as the Israeli man remembered it. I follow the onscreen tourist in astonishment as he wanders aimlessly through the once-sacred space; I recognize, as if from my own memories, the arches, the columns, the alcove for the Torah scrolls, the water line still visible in the remains of the ritual bath. The effect is like seeing a beloved dead relative in a dream. The past is alive, trembling within the present.

* * *

The problem is that Diarna’s ants are often working on top of a live volcano. This is a region where ISIS and other groups are hellbent on wiping out minorities, where political upheaval has generated the greatest human migration stream since the end of World War II, and where the deliberate destruction of priceless cultural artifacts sometimes happens because it’s Wednesday.

Mapping sites in this environment can require enormous courage—the hatred that prompted the Jews’ flight has long outlived their departure. Libya is one of many societies where Jews were violently rejected. Tripoli was more than 25 percent Jewish before World War II, but in 1945 more than a hundred Jews in the city were murdered and hundreds more wounded in massive pogroms, prompting the Jewish community’s flight. Later, the dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi expelled all remaining Jews and confiscated their assets. In 2011, after Qaddafi’s ouster, a single Libyan Jew who returned and attempted to remove trash from the wreckage of the city’s Dar Bishi Synagogue was hounded out of the country by angry mobs waving signs reading “No Jews in Libya”; apparently one was too many.

Earlier that year, a journalist in Tripoli offered to provide Diarna with photos of the once-grand Dar Bishi. “She slipped her minders and broke into the synagogue, which was strewn with garbage, and took pictures of it all,” Guberman-Pfeffer told me of the reporter. “Qaddafi’s men caught up with her and confiscated her camera—but the camera was the decoy, and she had pictures on her cellphone.” From her photos, Diarna built a 3-D model of the synagogue; the reporter still refuses to be named for fear of repercussions. Other Diarna researchers have resorted to similar subterfuges or narrow escapes. One Kurdish journalist who helped document Iraqi Jewish sites had to flee a poison gas attack.

Even those well beyond war zones often feel on edge. As I spoke with Diarna’s researchers—a mix of professionals, student interns and volunteers—many of them warily asked to let them review any quotations, knowing how haters might pounce on a poorly worded thought. One photographer, who cheerfully told me how he’d gotten access to various Diarna sites by “smiling my way in,” suddenly lost his spunk at the end of our conversation as he requested that I not use his name. If people knew he was Jewish, he confided, he might lose the entree he needed for his work.

“There’s a lot of blood, sweat and tears to get these images out to the public,” says Chrystie Sherman, a photographer who has done multiple expeditions for Diarna and who took the pictures of the destroyed synagogue in Damascus. Sherman was documenting Tunisian sites in 2010 when she decided on her own to go to Syria, despite rumblings of danger. “I was terrified,” she remembers. “I left all of my portrait equipment with a friend in Tunis, and just took my Nikon and went to Damascus and prayed to God that I would be OK.”

Following a lead from a Syrian woman in Brooklyn, she went to the country’s last remaining Jewish-owned business, an antiques shop in Damascus. The owner took her with other family members to the synagogue, which was no longer used for worship—and where his elderly father, remembering praying there years earlier, sat in his family’s old seats and broke down in tears. At another synagogue, Sherman was followed by government agents. “They asked why I was there, and I just told them I was a Buddhist doing a project on different religions. I didn’t tell them I was Jewish. You have to think on your feet.”

Sherman’s photographs for Diarna are incandescent, interiors glowing with color and light. Even her pictures from rural Tunisia, of abandoned synagogues in states of utter ruin, radiate with a kind of warmth, a human witness holding the viewer’s hand. “It’s hard to describe this feeling, which I have over and over again,” she says of her work for Diarna. “You are seeing centuries of Jewish history that have unfolded, and now everything—well, the world has just changed so dramatically and a lot of things are coming to an end. I was only in Syria for five days, and I was so excited to return with my portrait equipment. But then the Arab Spring began, and I couldn’t go back.”

* * *

You can’t go back. No one ever can. But it’s still worth trying.

Because of Diarna, I see my own American landscape differently. I pass by the tiny colonial-era cemetery near my home with its Revolutionary War graves, and I think of the histories that might lie unseen alongside the ones we enshrine, wondering whether there might be a Native American burial ground under the local Walgreens, whether I am treading on someone else’s ancient sacred space. I know that I must be. We are always walking on the dead.

Yet something more than time’s ravages keeps me returning to Diarna. As I was researching this essay, I found myself reeling from yet another anti-Semitic shooting in my own country, this one at a kosher market 20 minutes from my home—its proximity prompting me to hide the news from my children. A few days later, my social media feed was full of pictures from a different attack, at a Los Angeles synagogue where someone—whether hatefully motivated or simply unstable—trashed the sanctuary, dumping Torah scrolls and prayer books on the floor. The pictures remind me of Sherman’s jarring Diarna photos of a ruined synagogue in Tunisia, its floor strewn with holy texts abandoned in piles of dust. Our public spaces today, online and off, are often full of open derision and disrespect for others, of self-serving falsehoods about both past and present, of neighbors turning on neighbors. It’s tough these days not to sense an encroaching darkness. I’m looking for more light.

“It’s hard to recognize other viewpoints if you’re in a bubble where everyone thinks like you,” Ashkenazie tells me. He’s talking about homogenized societies in the Middle East, but he could be talking about anywhere, about all of us. “By raising this Jewish history, we’re puncturing these bubbles, and saying that in your bubble at one time not long ago, there once were others with you,” he says. “It’s not so crazy to welcome others.”

It’s not so crazy. I look through the images of our homes, all of our homes, the windows on my screen wide open. And I lean toward those sparks of light, glowing on a screen in a darkening world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/05/1805ad74-3f74-4a1b-b7d1-06c5c3ac3892/mobileopener_-_jun2020_f03_diarna_copy_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/04/0d049371-cd37-4054-aec1-b09af20b6f13/opener_-_jun2020_f03_diarna.jpg)