The Dawn of Television Promised Diversity. Here’s Why We Got “Leave It to Beaver” Instead

Using original archival research and FBI blacklist documents, a new book pieces together the intersectional narratives that never made it on air

:focal(201x131:202x132)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/59/e259db75-e7d4-4e37-b74f-4eaa5dd46ffe/leave.jpg)

“Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” is back on the air for its final season. It’s a triumphant curtain call for showrunners Aline Brosh McKenna and Rachel Bloom, who have spent the last three seasons lovingly unpacking the television show’s titular “crazy-ex,” and the oddball characters who inhabit her universe, under the rallying cry put forth in the show’s original theme song: “The situation is a lot more nuanced than that.”

If it feels like a small miracle that the ambitious musical-comedy-drama-you-name-it-it’s-not-supposed-to-fit-into-one-box show even made it on air, well, it almost didn’t. After Showtime opted not to move forward with the pilot, the project, termed a “risky proposition,” had to be saved by a pick-up from sibling network the CW.

Now a critical darling, “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” is part of a new class of television shows, including the likes of “Insecure,” “Jane the Virgin,” “Chewing Gum” and “Transparent” that share a mission to deconstruct the tropes set forth by television shows past. An opening salvo: diversifying the writer’s room. But for all the work these shows have done subverting the narratives traditionally told from the straight white male point of view, something deeply frustrating underpins their existence—the promise of what could have been on television decades earlier.

At the start of the Cold War, a prominent group of women, who had worked their way up in broadcast media in the 1930s and ’40s, were poised to use the new medium of television to create the kind of inclusive, intersectional content that is only today finding traction. Then, the blacklist, a vicious, hearsay-riddled manifest of Hollywood talent with ties to Communism, silenced their creative output. It effectively turned back on the dial of progressive representations on TV by decades.

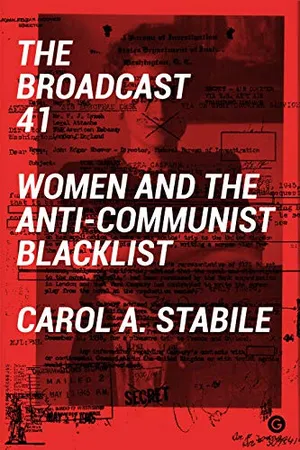

“It's hard for me to watch things and to hear about [today’s] writers and directors talk about their work without thinking about that earlier generation,” says Carol A. Stabile, a professor of women’s gender and sexuality studies at the University of Oregon and the author of the newly released book, The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist.

A much-needed addition to television scholarship, The Broadcast 41 uses original archival research and FBI documents to piece together the stories of the 41 women named on the list.

“The diverse group of people who are making television right now, these are the people that the Broadcast 41 dreamed of; they’re the people that they had hoped would be a more immediate future of television,” Stabile says.

Her book started with a question. A while back, she wondered: Why was it that when politicians talked about family values, they never used images of their own family? Instead, they used images pulled from television. “That's really weird, right?” she says. “The reference for family values is always this kind of mythic TV family.” She termed it the “Leave It to Beaver” syndrome, in reference to the 1950s program featuring a wholesome, suburban white family. “All these white [politicians], generations of them, had watched the sitcoms and watched reruns of the sitcoms, and they were really attached to them.”

It got her thinking, where did these sitcoms stem from? Were they reflecting the reality at the moment when television was just getting started? No, she found out, as she began her research; the situation really was a lot more nuanced than that. She started to unravel the stories of the women who were working in media industries at the end of World War II, some of whom, she realized, were very powerful. These successful career women produced content far different than the kind of sitcom representations of the world—of the career man, the housewife and their two children—that people wax nostalgic about today. And then, those women disappeared from the scene. “Why was that?” she wondered. The answer, she realized, was the blacklist.

“You can't read about that moment, or think about that moment, without thinking about the impact of what happened in 1950,” says Stabile.

1950 was the year that the American Business Consultants, comprised of former FBI agents, published the infamous book Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television. The unscrupulous organization—whose ostensible purpose was “exposing the ramifications of the Communist party”— racked up many abuses, including spying on individuals, printing lies in its publication Counterattack and impersonating active FBI agents.

Even the FBI’s New York Field Office called the American Business Consultants “highly unethical, irresponsible” and concluded they “should not be countenanced.” Despite that, the bureau did not put a stop to their activities. This was the rise of the Red Scare, after all. "Whatever the actual arrangement between the American Business Consultants and the Bureau," Stabile writes, "by 1949, the two groups had 'straighten[ed] out' any conflicts." The following year, the American Business Consultants published Red Channels, effectively ruining the careers and lives of those listed in it.

“This book, Red Channels, was known as the bible of the backlist,” Stabile explains. Of the 151 names it included, 41 were women. That felt like a large number to her, and so she began to dig into their lives and work in an attempt to understand the “threat” that they posed.

As she researched, she unearthed a prominent group of New Y0rk-based women who boldly challenged racist and sexist representation in media. “Things that we consider now to be intersectional, all of this was in the air in the 1930s and 1940s,” says Stabile. “There were queer women, cis-gender women, women of color doing these incredible things in theater, in radio.” She cites, for instance, Fredi Washington, an actress and journalist, who starred in an all-black cast theatrical production of Aristophanes' Lysistrata. “Something like that wouldn’t see the light of day again until Spike Lee’s [retelling in 2015’s] Chi-Raq,” she says.

Names you likely know are included on the list—the Dorothy Parkers, Lena Hornes and Lillian Hellmans of the world. But there are many names you probably haven’t heard of, either, like the Mexican-American actress and dancer Maria Margarita Guadalupe Teresa Estella Castilla Bolado y O’Donnell Alpert, who after being pushed out of the industry found a successful second life in arts education. Stabile also recounts the work that could have been—like writer Vera Louise Caspary's unaired pilots for "Apartment 3-G," which revolved around three single girls, and "The Private World of the Morleys," which followed the story of a woman striving to become a surgeon.

The backlash against progressives in media spared no one, Stabile says. Even those who weren’t named, like Gertrude Berg, the pioneering force behind “The Goldbergs,” suffered. Her show, first on radio and then television, was beloved for providing an insightful look at what life was like for Jewish-Americans. In the wake of the anti-communist fervor, though, “The Goldbergs” became a devastating example of self-censorship, where producers and writers suddenly stopped writing about “anything that might bother people,” as Berg put it herself. Her character, who once provided such a complex take on the immigrant experience, was reduced to a punchline.

When Stabile first started conceptualizing The Broadcast 41, she originally conceived it as case studies of several of the named women. But the more she researched, the more she wanted to use the sheer volume of them to make her argument. “That's a powerful block of women in the industry in New York City,” she says. She didn’t want to indirectly frame them as the exceptional woman of history, instead she sought to fold their story into the larger arc of women’s struggles. “This is a story about the collective loss of that group of really diverse women,” she says.

Many of the women in the Broadcast 41 knew one another. There weren't, after all, a lot of women in the industry, and for the women of color, they were part of an even smaller group, “a minority within a minority,” as Stabile says. The 41 met through many ways, including political organizations, performances and collaborations. Though they were all blacklisted as subversive Communists, their politics were across the spectrum. Still, they did all agree on certain things, such as civil rights. “I don't think that there's a woman on the list who wasn't involved in some kind of civil rights organization,” she says.

As Stabile read more, she found that, just like her, the Broadcast 41 were obsessed with those who came before them. “We all feel that when it comes to history, we get gaslighted,” she says. “It’s like all these people got wiped from history. For me that was an inspiration. Why do we all know about Lucille Ball, but we don’t know about Gertrude Berg?”

There’s so much, she says, that we still do not know about women’s role in and around the early years of television. “I spent so much time in archives around the country, and so much time reading FBI files and thinking, you know, nobody knows about these materials,” she says. “The work they had wanted to do, some of the work that they had done, it's all locked up in those spaces.”

That’s a loss for everyone. “[The blacklist] sets back representations and discussions of race by 30 years in this country,” Stabile estimates. “What gets amplified [instead on screen] are the sort of white supremacist tendencies and what gets suppressed is any kind of progressive narratives.”

What these women were producing before they were blacklisted was not necessarily a perfect reflection of the world. But, Stabile says, think about what we might have learned if those sorts of representations had set the groundwork then. “There's this constant cycle of criticism and innovation,” she says. “Once you censor those images, you can't learn from that. You can't get better.”

Looking at today’s political climate, she says it’s hard to imagine this was the world that people like the Broadcast 41 hoped for. At the same time, though, there’s a lot to embrace in the current moment. “The fact that we have Ava DuVernay and Shonda Rhimes and “Transparent,” all of those things, I think are going to make a difference,” she says. “That's why, for such a long time, they shut it down.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.