Behind the Scenes of Sandra Day O’Connor’s First Days on the Supreme Court

As the first female justice retires from public life, read about her debut on the highest court in the nation

:focal(781x207:782x208)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/75/0975cea2-a051-4f7c-b919-90e9574c5f28/mar2019_e07_prologue.jpg)

In 1981, when Ronald Reagan nominated Sandra Day O’Connor to become the first female justice on the Supreme Court, the bulletin led every TV news broadcast and major newspaper in the country and many abroad. The cover of Time magazine read, “Justice—At Last.”

O’Connor’s confirmation hearings that September became a huge media event. There were more requests for press credentials than there had been for the Senate Watergate Committee hearings in 1973. A new media institution—cable TV—carried the hearings live, a first for a judicial nomination. Tens of millions of people saw and heard a composed, radiant, hazel-eyed woman with a broad gap-toothed smile and large hands testify for three days before middle-aged men who seemed not quite sure whether to interrogate her or open the door for her. The vote to confirm her was unanimous.

Nearly 16 years before Madeleine Albright became the first female secretary of state, Sandra O’Connor entered the proverbial “room where it happens,” the oak-paneled conference room where the justices of the United States Supreme Court meet to rule on the law of the land. By the 1980s, women had begun to break through gender barriers in the professions, but none had achieved such a position of eminence and public power. The law had been an especially male domain. When she graduated from Stanford Law School in 1952, established law firms were not hiring women lawyers, even if, like O’Connor, they had graduated near the top of their class. She understood that she was being closely watched. “It’s good to be first,” she liked to say to her law clerks. “But you don’t want to be the last.”

Suffering from mild dementia at the age of 88, O’Connor, who retired from the court in 2006, no longer appears in public. But on a half-dozen occasions in 2016 and 2017, she spoke to me about her remarkable ascendancy.

* * *

At the Justice Department, the aides to Attorney General William French Smith had hoped that President Reagan wasn’t serious about his campaign promise to put a woman on the Supreme Court, at least not as his first appointment. Their preferred candidate was the former Solicitor General Robert Bork. But when Smith confided to his aides that Justice Potter Stewart planned to step down, he also told them the president had said, “Now, if there are no qualified women, I understand. But I can’t believe there isn’t one.” Smith eliminated any wriggle room: “It is going to be a woman,” he said.

Already, Smith had begun a list of potential justices, writing down five women’s names, in pencil, on the back of a telephone message slip that he kept on a corner of his desk. As he left the meeting, Smith handed the slip to his counselor, Kenneth Starr. Glancing at the list, Starr asked, “Who’s O’Connor?” Smith replied, “That’s Sandra O’Connor. She’s an appeals court judge in Arizona.”

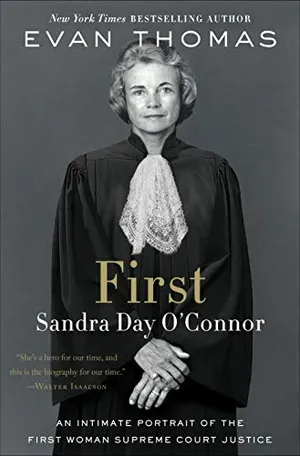

First: Sandra Day O'Connor

The intimate, inspiring, and authoritative biography of Sandra Day O’Connor, America’s first female Supreme Court justice, drawing on exclusive interviews and first-time access to Justice O’Connor’s archives

Even though she had been the first woman in any state senate to serve as majority leader, the Arizona intermediate court judge “was not as well known,” said Smith’s aide Hank Habicht. “She had no constituency”—with one important exception. Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist “came on strong for O’Connor,” Habicht recalled. He did so “privately, behind the scenes. He volunteered, just popped up. This was a boost for O’Connor. It made a difference.”

On June 25, Sandra O’Connor was in bed at her home in Phoenix, recovering from a hysterectomy. The phone rang and it was William French Smith. The attorney general was circumspect. Could she come to Washington to be interviewed for a “federal position”? O’Connor knew the call was momentous, but she answered with a sly dig. “I assume you’re calling about secretarial work?” she inquired. Smith was formerly a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher—the same Los Angeles firm that had, almost three decades earlier, rejected Sandra Day for a law job and asked her how well she could type.

On June 29, O’Connor flew to Washington to meet with the president. To maintain secrecy, she was told to wait outside a drugstore on Dupont Circle. Standing in a pastel suit (bought for the occasion at Saks Fifth Avenue) on a muggy, overcast day, she was picked up by William French Smith’s secretary and driven to the White House. No one recognized her.

Greeting her in the Oval Office, Reagan recalled that the two had met in Phoenix in 1972 at a Republican party “Trunk ‘n Tusk” dinner. He asked her a little about her judicial philosophy and then raised what he called “the sensitive subject” of abortion. But, O’Connor recorded in her notes on the meeting, “No question was asked.” She had already said that she thought abortion was “personally abhorrent,” but neither the president nor his men pressed her to say whether she favored overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling. Instead, the president and O’Connor chatted amiably about ranch life. Reagan seemed to be enjoying himself. After 40 minutes, the job was obviously hers.

* * *

On Tuesday, September 22, the day after O’Connor appeared triumphantly on the Capitol steps with Senators Barry Goldwater and Strom Thurmond and Vice President George H. W. Bush, Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote his brethren: “Now that Judge O’Connor has been confirmed by the Senate, we can proceed with plans that have been evolving over the last five weeks. The event being unique, the pressures for attendance at the ceremony and the reception and for press coverage are far beyond our capacity.” Justice Harry Blackmun had already written two letters to the court’s marshal huffily insisting that his family and law clerks were entitled to their “usual” front-row seats.

Blackmun was thin-skinned and insecure, especially about his opinion in Roe v. Wade, which had become a target of the Republican right. He regarded O’Connor as a likely ally of conservatives who wanted to overturn Roe v. Wade. At a Supreme Court reception before O’Connor’s swearing-in, a reporter asked Blackmun if he was ready for the “big day.” “Is it?” Blackmun snapped. Justice Thurgood Marshall was more lighthearted. He recalled that his swearing-in ceremony was celebrated with a plate of cookies.

At noon on Friday, September 25, Chief Justice Burger took the arm of Sandra Day O’Connor and walked her down the Supreme Court steps as hundreds of photographers, there for the photo session, snapped away. When Burger reached a plaza midway down the steps, he stopped and exclaimed to the reporters, “You’ve never seen me with a better-looking justice!”

O’Connor kept smiling. She was grateful to Burger and, by now, accustomed to him. O’Connor had long since determined to ignore minor diminishments. At the same time, she was perfectly aware of the importance of a dignified image. After her arrival in Washington, “Sandy” O’Connor, as some friends called her, increasingly became Sandra Day O’Connor.

The Supreme Court was grand and imperial outside but fusty and antiquated within. On the day O’Connor was sworn in, the elevator operator “tried to go from the 3rd floor to the 2nd floor and missed it and ended up on the 1st floor. It took him 5 minutes to get to the 2nd floor,” John O’Connor, Sandra’s husband, wrote in his diary. “We went to Sandra’s offices. They had just been vacated by Justice Stevens [who was moving into the chambers of retiring Justice Stewart]. They were pretty bare and plain.”

There was no furniture, not even a filing cabinet. Stacked up along the walls were piles of paper, some 5,000 petitions for writs of certiorari—requests for Supreme Court review, of which fewer than 200 would be accepted. The workload was staggering. A justice must read hundreds of legal briefs (O’Connor later estimated that she had to read over a thousand pages a day) and write dense, tightly argued memos to the other justices and then judicial opinions by the score.

At the opening of the court’s term the first Monday in October, O’Connor took her place on the bench. As the first case was presented, the other justices began firing questions at the lawyer standing at the lectern. “Shall I ask my first question?” O’Connor wondered. “I know the press is waiting—All are poised to hear me,” she wrote later that day, recreating the scene in her journal. She began to ask a question, but almost immediately the lawyer talked over her. “He is loud and harsh,” O’Connor wrote, “and says he wants to finish what he is saying. I feel ‘put down.’”

She would not feel that way for long. She was, in a word, tough. She could be emotional, but she refused to brood. She knew she was smarter than most (sometimes all) of the men she worked with, but she never felt the need to show it.

The next morning, O’Connor walked down the marble hallway to her first conference with the other justices. For secrecy’s sake, no one else is permitted to enter the conference room. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s secretary hesitated to knock on the door; she did not want to interrupt. By custom, the junior justice answers the door, takes notes and fetches the coffee. The brethren briefly worried that O’Connor might find the role demeaning for the first female justice, but decided that custom must go on. The court had just removed the “Mr. Justice” plaques on chamber doorways, but there was no ladies’ room near the conference room. She had to borrow a bathroom in the chambers of a justice down the hall.

By ritual, each justice shakes hands with every other justice before going out into the courtroom or into conference. On her first day, O’Connor grasped the meat-hook hand of Justice Byron “Whizzer” White, who had led the National Football League in rushing for the Detroit Lions. “It was like I had put my hand in a vise,” recalled O’Connor. “He just kept the pressure on and tears squirted from my eyes.” After that, O’Connor made sure to shake White’s thumb. In her journal entry that day, O’Connor noted, “the Chief goes faster than I can write,” and added, “It is my job to answer the door and receive messages.” On the other hand, she added, “I do not have to get the coffee.” Apparently, no justice had dared to ask.

O’Connor was accustomed to looking after herself. Still, she was a little lonely and a little lost. As the light died on ever shorter fall days, she would step out into one of the open-air interior courtyards and turn her face toward the pale sun. She missed the Arizona brilliance. In a way, she even missed the Arizona legislature, with all of its glad-handing and arm-twisting. She was surprised to find that within the Marble Palace the justices rarely spoke to each other outside of conference. Their chambers were “nine separate one-man law firms,” as one justice put it. With few exceptions, they did not visit each other or pick up the phone.

“The Court is large, solemn. I get lost at first,” she wrote in her journal on September 28, 1981. “It is hard to get used to the title of ‘Justice.’” A few of the other justices seemed “genuinely glad to have me there,” she wrote. Others seemed guarded, not only around her but even around each other. At the regularly scheduled lunch in the justices’ formal dining room that week, only four of her colleagues—Chief Justice Burger and Justices John Paul Stevens, William Brennan and Blackmun—showed up.

Burger usually meant well, but he could have a tin ear. In November, after O’Connor had been on the court for less than two months, the chief justice sent the newest justice an academic paper entitled “The Solo Woman in a Professional Peer Group” with a note that it “may be of interest.” Examining the ways men behave toward a lone female in their group, the paper concluded that the woman’s presence “is likely to undermine the productivity, satisfaction, and sense of accomplishment of her male peers.” Unless the group openly discusses her status as a woman, the paper counseled, the woman should be willing to accept a more passive role.

O’Connor routinely answered any communications. There is no record in her papers that she answered this one.

She had hoped—and expected—to get a helping hand from Bill Rehnquist. In her journal, she regarded her old friend coolly. While noting that “Brennan, Powell, and Stevens seem genuinely glad to have me there,” with “Bill R., it is hard to tell. He has changed somewhat. Looks aged. His stammer is pronounced. Not as many humorous remarks as I remembered from years ago.” Cynthia Helms, perhaps O’Connor’s closest Washington friend, recalled O’Connor’s saying to her “You get there, and you’re in this big office and you have all these briefs, and Bill was no help at all.”

Rehnquist was arriving late to the court and leaving early. He had been laid low by pneumonia in the summer, and in the autumn his chronically bad back worsened. And he had another reason to keep his distance from O’Connor, said Brett Dunkelman, a Rehnquist clerk, who spoke to me in 2017. “They had been such lifelong friends. He didn’t want...” Dunkelman paused, searching for the right words. “Not to show favoritism, exactly, but he didn’t want his personal relationship to color his professional relationship.” Rehnquist knew that his brethren were aware that he had dated O’Connor at Stanford law school. (They did not know that he had actually asked her to marry him.) Blackmun did not let him forget it. When O’Connor joined the justices on the bench in October, Blackmun leaned over to Rehnquist and whispered, “No fooling around.”

In her outer office, sacks of mail piled up. She received some 60,000 letters in her first year—more than any other justice in history. Some of the letters were pointedly addressed to “Mrs. John O’Connor.” One said, “Back to your kitchen and home, female! This is a job for a man and only he can make tough decisions.” A few angry men sent her naked pictures of themselves. O’Connor was taken aback by this ugly, primitive protest, but she shrugged off insults and innuendo and focused on the job at hand.

Justice Lewis Powell came to the rescue. “Dad told me Justice O’Connor’s secretary was a train wreck, and Justice O’Connor needed help,” recalled Powell’s daughter, Molly Powell Sumner. “He gave her a secretary from his own chambers.” It was the beginning of a deep friendship with the courtly Powell.

In the conference room, Powell pulled out O’Connor’s chair for her and stood when she entered. O’Connor appreciated his old-school manners. In turn, Powell was impressed, and possibly surprised, by O’Connor’s acute intelligence as well as her charm. When he wrote his family on October 24, only three weeks into the court term, that “it is quite evident that she is intellectually up to the work of the Court,” it was obvious he had been measuring her. He added, “Perhaps I have said that she is the number one celebrity in this town!” Six weeks later, he wrote, “You know by now that we find the O’Connors socially attractive, and she is little short of brilliant. She will make a large place for herself on the Washington scene.”

None of O’Connor’s law clerks doubted that she was in charge. She had no record, no experience with constitutional law, no clearly articulated views or established doctrine to follow. Yet she did not have any trouble deciding. She was rarely relaxed, but she was almost always calm. “She occasionally lost her temper, but in a very reserved way. She never yelled or screamed, but we knew who was the disfavored clerk that week,” Deborah Merritt, one of her clerks, recalled.

In the court’s weekly conference, the junior justice votes last. O’Connor recalled that she felt “electric” at her first conference, on October 9, 1981. On the very first case, the justices were split four to four and then it came to her. She felt “overwhelmed” to be at the table at all—and yet thrilled to be “immediately” in the position to cast the decisive vote. This was a power she had never felt when she was herding fractious lawmakers in the Arizona senate. The stakes were far higher than any judicial docket she had faced in the state courts.

Behind O’Connor’s mask of self-control was an exuberance, a fulfillment of her father’s bursting pride. Merritt was in O’Connor’s chambers when the justice returned from that first conference. “She came back almost girlishly excited,” Merritt recalled. “I know that sounds sexist. But she wasn’t in her stoic mode. She had found it so amazing. How they went around the table. She was surprised there was not as much discussion as she expected, but also at how weighty the issues were. And she seemed to be saying, ‘I did it! I survived! I held my own!’”

A New Order in the High Court

When RBG arrived, a Supreme sisterhood took root

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/84/fc84f7f3-39a2-4879-b680-c0f6e88ddb23/mar2019_e34_prologue.jpg)

In 1993, when President Bill Clinton appointed Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the Supreme Court, O’Connor was relieved to have a second female justice, and not just because the court finally installed a women’s bathroom in the robing room behind the bench. “I was so grateful to have company,” O’Connor told ABC correspondent Jan Crawford Greenburg. Nervous lawyers occasionally confused their names, even though they looked nothing alike.

The two women were friendly but not cozy. When it really mattered, though, they helped each other. Ginsburg was diagnosed with cancer in 1999, and O’Connor advised her to have chemotherapy on Fridays, so she could be over her nausea in time for oral argument on Monday, as O’Connor herself had done when she was treated for breast cancer ten years earlier.

Soon after arriving at the court, O’Connor wrote the court’s 1982 opinion in Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, an important step forward in women’s rights. O’Connor’s opinion was so attuned with the views of Ginsburg, then a Court of Appeals judge, that Ginsburg’s husband had teasingly asked his wife “Did you write this?” In 1996, the court voted that the all-male Virginia Military Institute must accept women, and O’Connor was chosen to write the majority opinion. Generously, shrewdly, O’Connor demurred, saying, “This should be Ruth’s opinion.” When Ginsburg announced the result in United States v. Virginia on June 26, 1996, ruling that the government must have an “exceedingly persuasive justification” for discrimination based on gender—and citing O’Connor’s 1982 precedent in Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan—the two women justices exchanged a knowing smile. O’Connor had understood that Ginsburg would be honored to open up a last male bastion while advancing the law on sex discrimination. Ginsburg told me, “Of course, I loved her for that.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.