The Bonsai Tree That Survived the Bombing of Hiroshima

Now living in Washington, D.C., this bonsai tree outlasted the atomic blast

On August 6, 1945, at a quarter-past 8 a.m., bonsai master Masaru Yamaki was inside his home when glass fragments hurtled past him, cutting his skin, after a strong force blew out the windows of the house. The U.S. B-29 bomber called the “Enola Gay” had just dropped the world’s first atomic bomb over the city of Hiroshima, at a site just two miles from the Yamaki home.

The bomb wiped out 90 percent of the city, killing 80,000 Japanese immediately and eventually contributing to the death of at least 100,000 more. But besides some minor glass-related injuries, Yamaki and his family survived the blast, as did their prized bonsai trees, which were protected by a tall wall surrounding the outdoor nursery.

For 25 years, one of those trees sat near the entrance of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum at the United States National Arboretum in Washington D.C., its impressive life story largely unknown. When Yamaki donated the now 390-year-old white pine bonsai tree to be part of a 53 bonsais gifted by the Nippon Bosnai Association to the United States for its bicentennial celebration in 1976, all that was really known was the tree’s donor. Its secret would remain hidden until 2001, when two of Yamaki’s grandsons made an unannounced visit to the Arboretum in search of the tree they had heard about their entire lives.

Through a Japanese translator, the grandsons told the story of their grandfather and the tree’s miraculous survival. Two years later, Takako Yamaki Tatsuzaki, Yamaki’s daughter also visited the museum hoping to see her father’s tree.

The museum and the Yamaki family maintain a friendly relationship and it is due to these visits that the curators know the precious value of the Yamaki Pine.

“After going through what the family had gone through, to even donate one was pretty special and to donate this one was even more special,” says Jack Sustic, curator of the Bonsai and Penjing museum. Yamaki’s donation of this tree, which had been in his family for at least six generations, is a symbol of the amicable relationship that emerged between the countries in the years following World War II. Dignitaries in attendance at the dedication ceremony for the trees included John D. Hodgson, ambassador to Japan, Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger who said the gift from Japan represented the "care, thought, attention and long life we expect our two peoples to have."

Today, more than 300 trees make their home at the museum, including bonsai grown in North America and penjing, the Chinese bonsai equivalent.

There are many misconceptions about bonsai, Sustic says. It’s not a type of tree because anything with a woody trunk can be bonsai. Rather, it’s an art form and for the bonsai master, “it’s a lifestyle,” he explains. Another common error is the proper pronunciation of bonsai; it’s BONE-sigh, not BAHN-sigh.

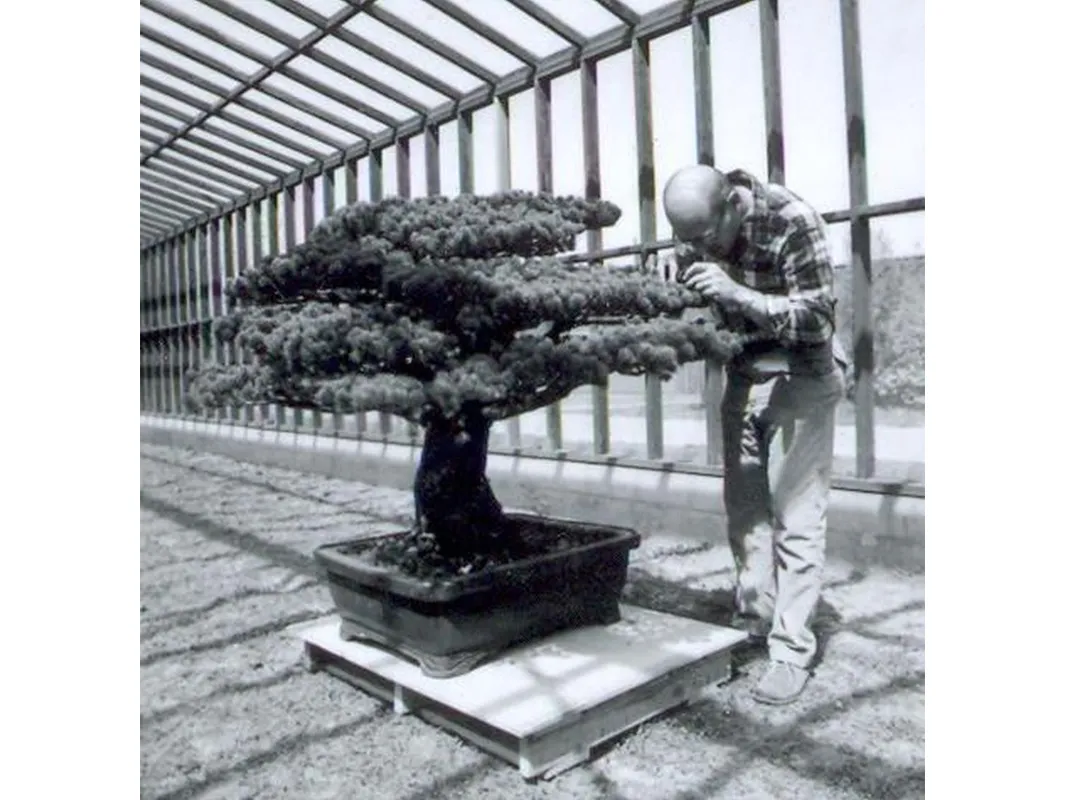

Bonsai trees can be cultivated from trees collected in the wild or in rare cases from seeds; for those whose thumbs are a little less green, they can be purchased at a nursery. They are planted in large containers and pruned frequently to maintain their silhouette. Sometimes, as in the case of the Yamaki Pine, multiple trees are grafted together to enhance the appearance of the tree. Though bonsai masters maintain a degree of artistic freedom they still look to nature for inspiration, recreating what they see in the natural world on a bonsai scale.

“It’s a marriage between horticulture and art,” but it’s unique because it’s always growing,” Sustic says while admiring the Yamaki Pine.

Because they are always growing, bonsai trees require daily attention. Sustic even likens caring for a bonsai tree to having a pet. But it’s due to this constant attention that bonsai like the Yamaki Pine live beyond the natural life expectancy of the trees from which they come.

The Yamaki Pine will take its familiar place near the entrance to the museum’s new Japanese Pavilion when it officially opens next year, and on this 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, the tree serves as a reminder of the continued peace between the United States and Japan.

“It’s a very special tree,” Sustic says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)