SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

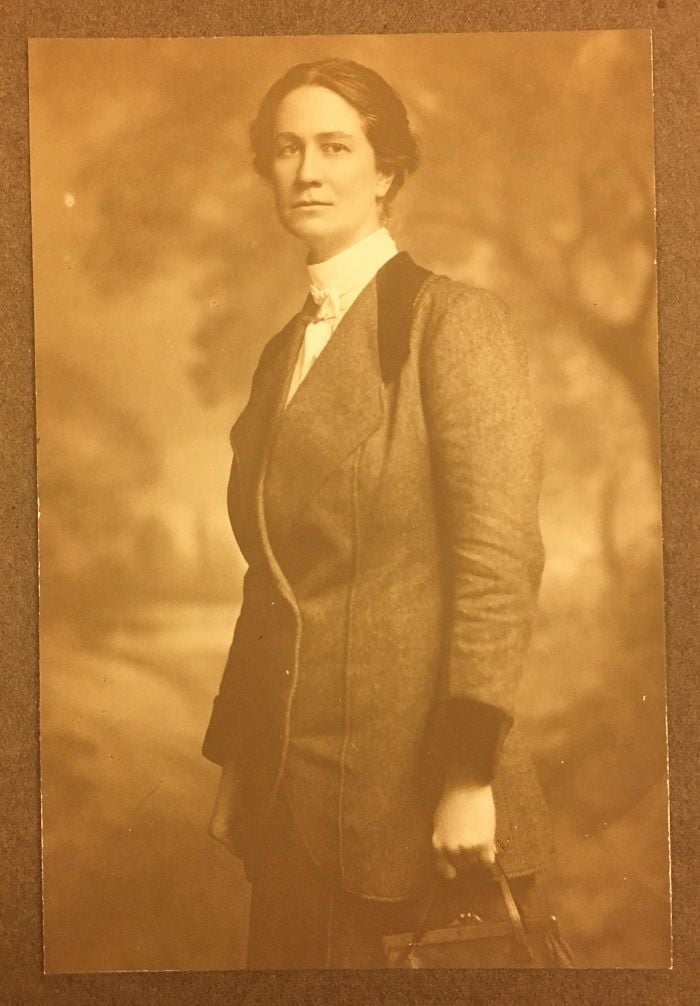

Meet Serena Katherine “Violet” Dandridge, Suffragist and Scientific Illustrator

The history of Violet Dandridge’s investment in her work as a scientific illustrator and a suffragist, told in her own words, helps us construct a more complete picture of what it meant to many women to pursue careers and basic rights in the early twentieth century.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/f1/7bf111c9-0818-4292-8d10-7be8f22c1d17/violet-tweed-suit-header.jpg)

Serena Katherine “Violet” Dandridge (1878-1956) was one of the Smithsonian’s first female scientific illustrators and a supporter of women’s suffrage. Dandridge grew up in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, and moved to Washington, D.C. in 1896 to study art. Sometime in the first decade of the twentieth century, she began working with zoologists at the Smithsonian, particularly Mary Jane Rathbun and Austin Hobart Clark, to produce drawings and paintings of specimens for publication and exhibition.

Dandridge has long been a person of interest to staff working at the Smithsonian Institution Archives and the National Museum of Natural History. From Curators’ Annual Reports, we know that for a month in August 1911, Dandridge and Mary Jane Rathbun traveled to South Harpswell, Maine and Woodshole, Massachusetts to research the colors of marine animals for an upcoming museum exhibition. Incidentally, the two returned to the Smithsonian with a large collection of specimens.

Eventually, Dandridge moved home to West Virginia, but she continued working as an illustrator. From correspondence between Dandridge and Austin Hobart Clark we know that Dandridge truly valued her work with the Smithsonian. And records from Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library also reveal the importance that Dandridge placed on her career. In a letter from those archives, dated February 24, 1914, Dandridge wrote to her parents from a hospital asking them to limit her hospitalization (for bouts of “nervousness”) to two weeks so that she could continue with her work:

[I]t is not wise from my business’ point of view to keep me here more than the two weeks. You see my chief business asset has got to be reliability, they must feel they can trust me and that I have good sense or they won’t continue to give me this new and original work. I know you and mother would be the last people to do anything that would interfere with my getting good work particularly now that I’ve gotten them up to the point of sending fishes out of the museum to me.

But her concerns went beyond her own work. During her hospitalization, according to the superintendent, Dandridge refused to eat, because “she wishe[d] to die on account of man’s injustice to woman.” Duke’s archives further show that Dandridge supported women’s rights through the suffrage movement. From their records, we learn that Dandridge subscribed to The Suffragist, gave money to the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, and arranged for a National American Woman Suffrage Association speaker to visit her hometown. And in 1915, The Washington Post listed “Miss Violet Dandridge” as a registered delegate from West Virginia at the Annual Convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

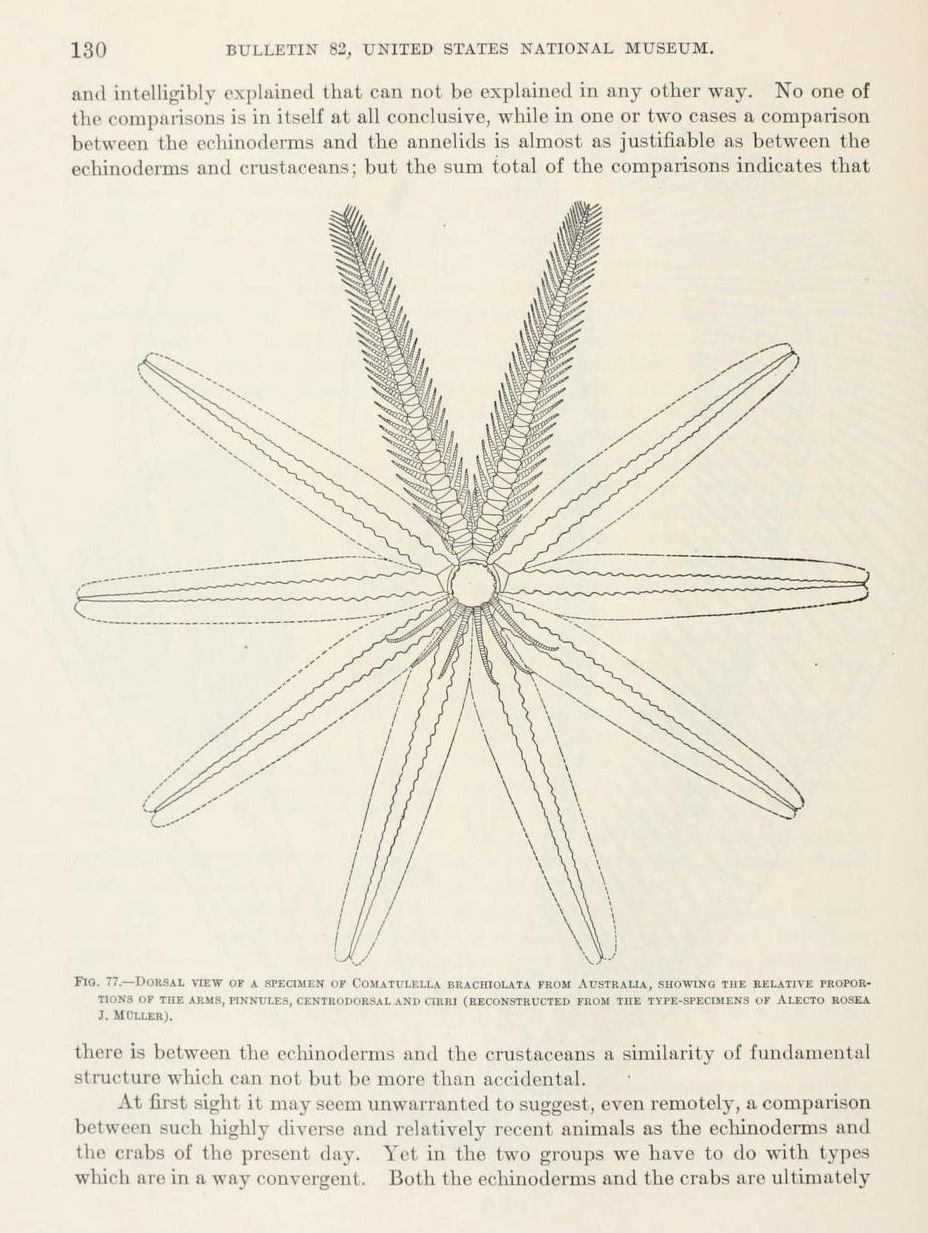

Today, this history of Violet Dandridge’s investment in her work as a scientific illustrator and a suffragist, told in her own words, helps us construct a more complete picture of what it meant to many women to pursue careers and basic rights in the early twentieth century. This history also establishes Dandridge as an important early contributor to scientific research at the Smithsonian. A search for “Violet Dandridge” in early twentieth century Smithsonian reports and bulletins yields a rich set of results that include many drawings by Dandridge and thanks for her skills. To see the lasting impact that Dandridge has had on Smithsonian history, search for her name in the digital collections made available by the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

For more information regarding other women in science who contributed to the suffrage movement, you can take a look at some previous Smithsonian Institution Archives blog posts that have highlighted women in science who fought for the right to vote. Entomologist and medical doctor, Evelyn Groesbeeck Mitchell, joined the National Woman American Suffrage Association. And Mary Agnes Chase, a botanist specializing in grasses at the United States Department of Agriculture and the Smithsonian, actively participated in National Woman’s Party protests.

Related Collections

- United States National Museum, Curators’ Annual Reports, Record Unit 158, Smithsonian Institution Archives

- Bedinger and Dandridge Family Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Related Resources

- “New Suffragist Host: National Association Arrives as Rival Delegates Depart,” The Washington Post, Dec 13, 1915, page 3.