OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

Reversing the Erasure of Native Contributions to Muralism

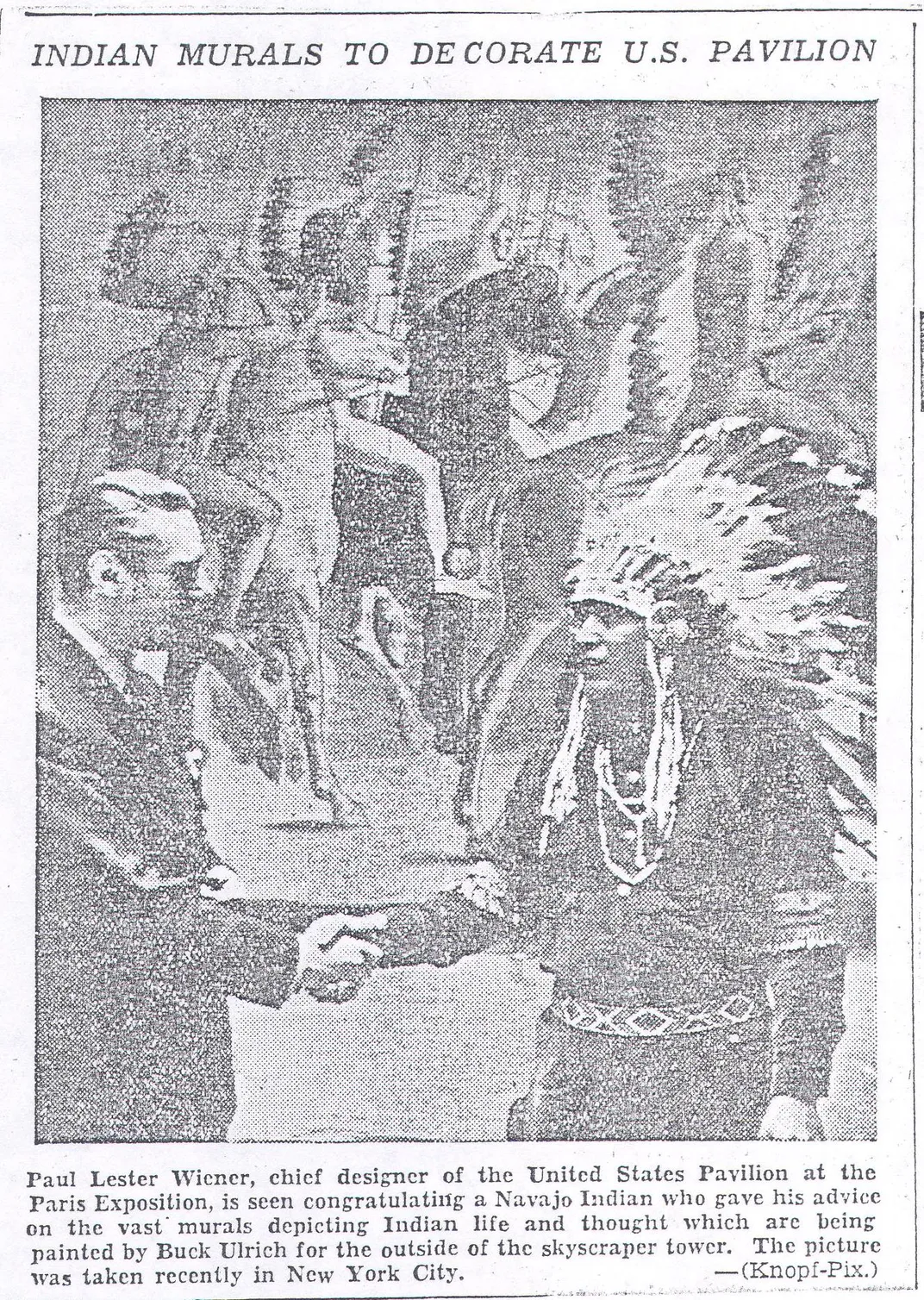

One document in particular has occupied my thoughts in the months since my visit: a newspaper clipping showing two men shaking hands. The men stand in front of Ulreich’s mural Indians Watching Stagecoach in the Distance (1940), which he painted for the post office in Columbia, MO. The man on the left is named in the caption as the 1937 U.S. pavilion’s architect, Paul Lester Wiener, while the one on the right, appearing in a feathered headdress, is identified simply as, “a Navajo Indian who gave his advice on the vast murals depicting Indian life and thought which are being painted by Buck [sic.] Ulreich for the outside of the skyscraper tower.” My goal, ultimately, is to identify this man. Yet even without this man’s identity, the photograph highlights an oft-overlooked aspect of twentieth-century American art: the essential contributions of Native Americans to the mural movement that overtook the United States in the years between World War I and World War II.

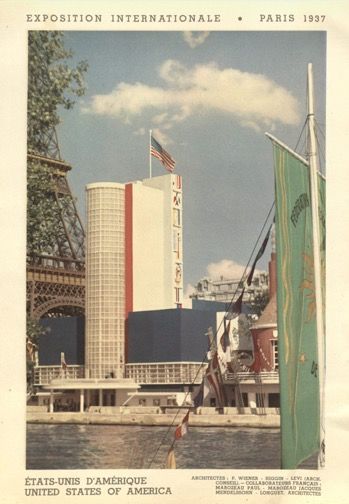

Being an art historian is a little like being a detective. It sometimes takes me to unlikely places—including, recently, a basement outside St. Louis, where the relatives of an artist I was researching for my dissertation generously allowed me to review documents from his life. The artist, Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, had designed a number of publicly funded murals throughout his career; studies for many of them can be found in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery (SAAM). My interest in Ulreich was related to two 88-foot wooden panels inspired by Native American symbols that he conceived for the United States Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.[1] One document in particular has occupied my thoughts in the months since my visit: a newspaper clipping showing two men shaking hands. The men stand in front of what appears to be Ulreich’s mural Indians Watching Stagecoach in the Distance (1937), which he painted for the post office in Columbia, MO. The man on the left is named in the caption as the 1937 U.S. pavilion’s “chief designer,” Paul Lester Wiener, while the one on the right, appearing in a feathered headdress, is identified simply as, “a Navajo Indian who gave his advice on the vast murals depicting Indian life and thought which are being painted by Buck [sic.] Ulreich for the outside of the skyscraper tower.”[2] My goal, ultimately, is to identify this man. Yet even without declaring this man’s identity, the photograph highlights an oft-overlooked aspect of twentieth-century American art: the essential contributions of Native Americans to the mural movement that overtook the United States in the years between World War I and World War II.

Ulreich was one of the many U.S. artists who received funds to install murals in public buildings in the United States during the 1930s and early 1940s through programs such as the Public Works of Art Project, the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, and the Works Progress Administration. He styled himself as a “Cowboy-Painter,” a claim that lay in part in his avowed knowledge of Native American cultures.[3] The artist was vocal about time he had spent around Native Americans, including as an actual cowboy on a ranch on an Apache reservation in Arizona. He posited that it was this type of exposure that resulted in his selection to paint the exposition murals.[4] Yet as the newspaper clipping indicates, Ulreich required the input of at least one Native advisor to accurately convey the mural’s symbols. A different clipping in Ulreich’s family’s archive identifies a number of the symbols that appear, stacked on top of one another, in the pavilion’s murals. These include a “Kachina”[5] figure popular in Pueblo cultures, a Crow thunderbird, and an adaptation of a deity used in Navajo[6] sand painting.[7] This same clipping indicates that, although Ulreich designed the murals, a “member of the Navajo tribe” actually painted them. This individual, like the man in the photograph, is unnamed in the clippings. Neither appears to be mentioned at all in fair-sponsored publications and they are absent altogether from what limited secondary literature exists about the U.S. pavilion at the 1937 exposition.

The 1937 fair was not the first world’s fair to feature murals indebted to Native American labor and knowledge. The 1933 Century of Progress exposition in Chicago had included a series of murals executed by a group of artists associated with the Santa Fe Indian School. Changing perceptions of Native culture, reflected in the work of both Native and non-Native artists alike, were in fact a hallmark of the mural movement in the United States. In addition, one of the movement’s most revolutionary aspects was an increased access to the role of “artist.” Not only men of European descent, but also many women, Native Americans, and other people of color became muralists. Still, artists from these marginalized groups did not receive the same treatment as their white male counterparts. Like the Native participants in the 1937 exposition, the artists who developed the Century of Progress murals are anonymous in fair literature. One administrative document refers to them simply as the “Santa Fe Indians,” while it refers to white artists such as George Biddle and John Norton by name.[8] Thanks to the work of art historians such as Jennifer McLerran, we know the identities of many of the mural artists involved with the Santa Fe Indian School. Several of these are represented in SAAM’s collection, including Julian “Pocano” Martinez, Tse Ye Mu (known alternately as Romando Vigil), Awa Tsireh (known alternately as Alfonso Roybal), Oqwa Pi (known alternately as Abel Sanchez), and Ma Pe Wi (known alternately as Velino Shije Herrera), whose murals can also be found in the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C.[9]

To identify the Native individuals who helped create the panels at the 1937 fair would ensure that they are given credit, if belated, for their work. Beyond this, it would be a means of celebrating Native contributions to the mural movement. Native participation in the painting of such monumental, public works of art during this period is little known and seldom discussed, a problem that is compounded when we do not know the names of the individuals who took part. The erasure of nonwhite groups from public life is particularly dangerous, as it has a pernicious history in this country. From attacks on Black communities to anti-immigrant rhetoric, the claim that only white Americans “create,” while others sponge off their productivity, has been one of the most insidious myths shoring up the ideology of white supremacy over the last several centuries.[10]

Searching for the identity of the man in the 1937 photograph is a small way of combatting this myth. It is a way of ensuring that white artists do not receive the only credit for their collaborations with communities of color. I am therefore hoping that anyone who might have information about the man in the photograph or other Native participants in the 1937 exposition will get in touch! With such interventions, perhaps art history can help to make the inclusiveness promised by muralism a reality.

[1] Carlyle Burrows, “A New Project in Modern Decoration: The Stage Coach and the Pony Express,” New York Herald Tribune, August 1, 1937, F6.

[2] Art historian Emily Burns notes that the man’s dress appears to be a composite of clothing from a number of different Native nations. The headdress, for example, is typical of Plains rather than southwestern cultures. It thus constitutes a kind of Native American “intern-nationalism” against the backdrop of the International Exposition. Emily Burns, email message to the author, September 30, 2020.

[3] “With Latin Quarter Folk,” Folder “1926,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[4] Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, “Eduard Buk Ulreich: A Brief History,” n.d., Folder “Buk Autobiography,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO; “Story of the Indian Ornament for the American Exposition Building at Paris, France,” n.d., Folder “1937,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[5] The term “katsina” (plural “katsinam”) is preferred.

[6] Members often prefer the name “Diné” to Navajo.

[7] Francis Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore of U.S. Indains at Exposition,” Paris Herald, July 27, 1937, Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[8] “Interior Painting & Murals,” n.d., Series 15, Box 7, Folder 15-74, Century of Progress World’s Fair, 1933-1934 (University of Illinois at Chicago).

[9] See Jennifer McLerran, A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Arts and Federal Policy, 1933-1943 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012), 164.

[10] See, for example, Josh Levin, “The Frenzy at David Duke’s Campaign Rallies,” July 8, 2020, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/07/david-duke-1990-senate-race-rallies.html.