How Art Can Foster Social-Emotional Awareness for Our Students (and Ourselves)

Museum educators at the National Museum of Asian Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum have developed programs to equip teachers and students alike with strategies to slow down. This programming has guided participants in appreciating art, checking-in with themselves, and developing empathy.

:focal(2592x1728:2593x1729)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/89/a589f303-113a-4f59-ad0e-9019fb20ae3f/img_4061.jpg)

The last two years have been extremely taxing on the well-being of classroom educators and their learners. Teachers are feeling burnt out, underappreciated, and are leaving the field in record numbers. According to a RAND June 2021 survey, teachers were almost three times more likely to report symptoms of depression than other adults. Over the past two years, teachers have been reporting that students are regressing in emotional intelligence (the ability to recognize, understand, and manage one’s own emotions) and are having difficulty regulating their emotions and maintaining classroom normative behaviors. These observations are substantiated by the U.S. Surgeon General’s December 2021 warning of a “devastating” mental health crisis for teens.

Smithsonian educators Elizabeth Dale-Deines and Jennifer Reifsteck recognized that teachers and students need resources to help identify and manage their emotions, recognize their resilience, and practice self-care and mindfulness. Each leveraged their respective museum’s collections – Elizabeth at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and Jennifer at the National Museum of Asian Art (NMAA) – and worked alongside community partners to develop tools for teachers and students to develop social-emotional learning skills.

What is social-emotional learning? The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines social-emotional learning as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions.” Dale-Deines and Reifsteck looked to the CASEL framework to develop their resources with their partners.

“In 25 years of teaching, I have witnessed the intensifying of stress/anxiety in my students, all of whom work and live within a system of high expectations for their success,” said one 10th grade English teacher. Add the social atrophy borne of the COVID-19 pandemic and we begin to understand why supporting students’ ability to slow down and connect to others is so valuable.

Slowing Down

In October 2020, the National Museum of Asian Art, in partnership with mindfulness education non-profit Create Calm, launched the Artful Movement virtual field trip program for PreK-6th grade audiences. Artful Movement combines breathing practices, slow looking at art, and movement inspired by the work of art. In terms of Social and Emotional skills development, students recognize their emotions, learn stress management techniques, and develop their cultural competencies by participating in the virtual field trip. Since its inception, over 800 students and educators have participated in the Artful Movement virtual field trip.

“We wanted the virtual field trip to recognize our inner strength and resilience during a time that felt so chaotic. We wanted to give students reminders of what they could control, like their breath, and how they can use the breath and their bodies as tools to find calm,” says Jennifer Reifsteck, Education Specialist, K-12 Learning at the National Museum of Asian Art.

Lisa Danahy, Founder and Director of Create Calm, notes the skills learned during the virtual field trip: “Artful Movement not only provides an opportunity for students to develop skills of reflection and communication. The program offers a practice space in which children learn to manage their bodies and emotions and become more effective and independent problem solvers.”

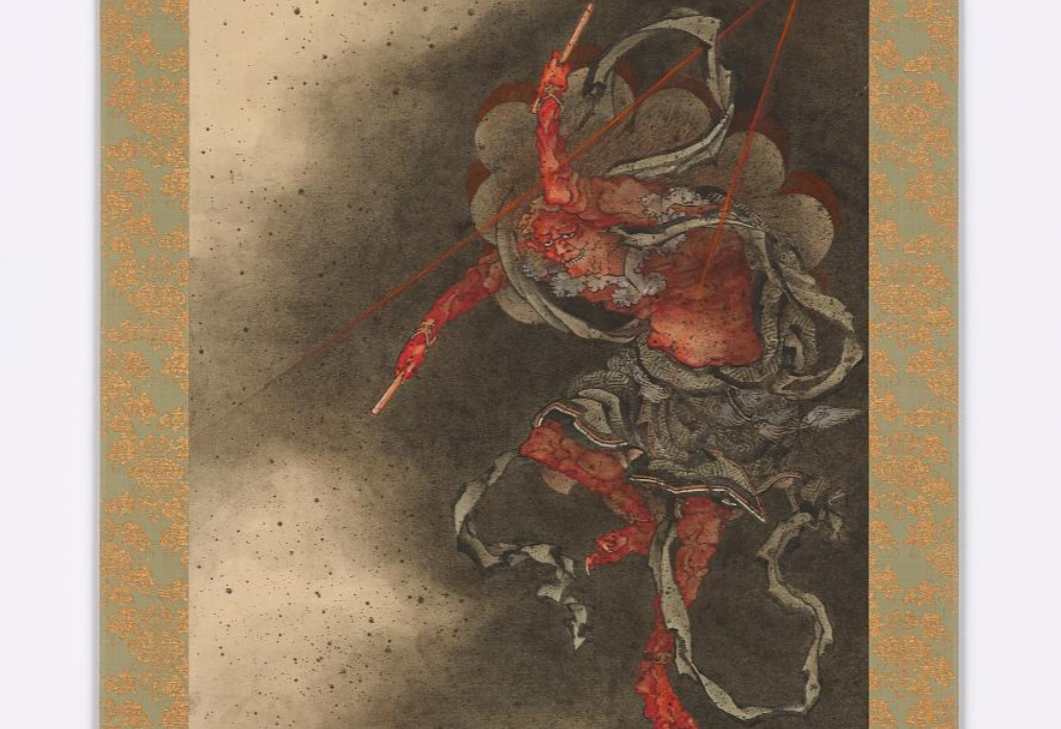

Create Calm and National Museum of Asian Art educators selected Hokusai’s Thunder god as the focus object for Artful Movement. The background of the hanging scroll depicts a large, swirling cloud set against a black sky with red laser beams of lightning shooting from the corner of the painting. Floating in front of the ominous sky is the Thunder god who seems as dynamic and energized as the background.

Many students see the red, bumpy skin and the spiky grin of Hokusai’s Thunder god and label the being as a demon. After students share their perspectives, they learn from the educator the title of the painting and that red in Japanese art is a symbol of power and vitality. Then, they metaphorically move their bodies from a rain drop to a cloud, then to wind, rain, crashing lightning and booming thunder. After the storm, they settle into a puddle, with an invitation to ponder the nourishment they provided to the earth. With this new knowledge, they perhaps begin to see the Thunder god as a benevolent, helpful being.

“Slow looking allows one to see beyond what can be noticed at first glance. Through closer inspection and more information, you may experience a perspective shift. Slow looking at art is a powerful, transferable skill that allows one to uncover biases and prejudices,” says Reifsteck.

Connecting with Others

To address the issue of diminished social skills and behavioral issues, the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) developed a series of journaling exercises in consultation with classroom teachers and art therapists. The approach begins with a check-in, such as asking a student how they are feeling today. Then it offers a framing question: “Describe a time when you had to solve a problem on a team, and you disagreed with your teammate. How did your disagreements impact the conversation? Your problem-solving skills?”

So, try it out! How does disagreement affect your conversational or problem-solving skills?

Next, the approach invites students to practice interpersonal skills with artworks as their conversation partner. They begin by considering their own emotional state, then shift to curiosity about others’ perspectives. Moving ever wider, they look for community connections and finally the strengths they themselves can share in service to others.

Just like NMAA’s activity, SAAM’s approach hinges on looking carefully at an artwork that initially feels strange or unfamiliar and developing empathy. Try it!

Look at the three works below. Which one feels the least familiar? Focus on it...

-

Look closely at the least familiar artwork for 10 seconds. Write down a list of five things you can see. Then, list another five things.

-

How do you think the figures in the scene feel? What makes you say that?

-

If you had to ask three questions to better understand what’s happening in the scene, what would you ask? Write these down, then write down three more.

-

Read through all the questions you posed. Which ones require only a yes/no answer? Choose one of those yes/no questions and try asking it a different way. How might the answer change?

One teacher reviewer commented: “I especially liked the section where the students wrote questions for a figure in the artwork, and then re-phrased the questions.” She had a rich conversation with her middle school students “...about how the phrasing of a question can inadvertently alienate the listener, especially if the question makes an inaccurate or off-putting assumption. (Example: Why are you sad?)”

SAAM’s newest SEL resource will be available in print and online in Fall 2022 in Spanish and English. Email [email protected] for more information.

As you look up from your computer and connect with your students, coworkers, or family members, look for opportunities to check in with yourself. How are you feeling? What seems strange to you in the world? What might you gain from maintaining a stance of curiosity?

Editor's Note: To learn more about the use of art to support social-emotional learning skills, join Jennifer Reifsteck and Elizabeth Dale Deines at the Smithsonian's National Education Summit on July 27-28, 2022. More information is available here: https://s.si.edu/EducationSummit2022 .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/ea/24ead0a3-2937-49f0-a64a-b488365efa61/saam-19975_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/3f/c33f027c-aa73-44b3-9678-cd673b8028e1/saam-2006249_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/12/6e12c714-36cf-4613-a3ca-791d5d1607ec/saam-1991171_1.jpg)