Teaching a More Complete Picture of MLK

While Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech was a pivotal moment in U.S. history, there’s more to his life and legacy than that single story. Smithsonian educators share approaches to expand classroom lessons and student understanding of this great civil rights leader.

![A black ink on a red-orange poster board with a small picture of Martin Luther King, Jr. at the top left and Joseph Lowery at the top right. The poster reads: [SCLC / INJUSTICE / Anywhere... / a threat to / JUSTICE / EVERYWHERE / M. L. KING].](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/WPW8xOyFYnIPvTWF-qUKQvX_mL0=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale():focal(350x417:351x418)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/fa/abfad35f-1831-4f62-b159-5cf422d0dbfb/nmaahc-994f4b3172042_1001.jpg)

Educators nationwide are undoubtedly considering how to expand upon student understanding of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and legacy, as both his namesake holiday and Black History Month approach. Below, three museum educators offer their ideas to seize this opportunity for substantive lessons in the classroom - now and year round. They look to expand upon what traditional textbooks and mainstream media might share about King to build a more contextualized, nuanced understanding of the complexity of the man and his contributions to many impactful movements in the 20th century.

By examining primary sources, ranging from photographs (both in black and white and color) to pins and protest flyers, we can widen our lens to acknowledge the range of King’s ideas throughout his lifetime. And by analyzing both contemporaneous and later artworks that were created in response to King’s assassination, we consider his impact on the nation and perspectives we might not have considered before.

Expanding the Traditional Narrative to Better Understand King’s Impact

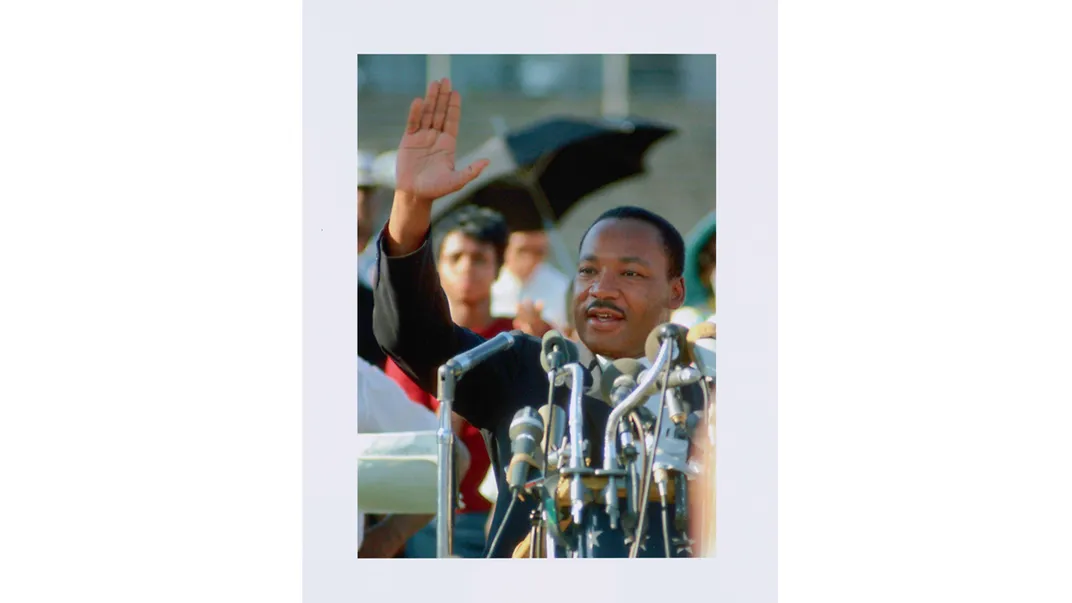

When people visualize Dr. Martin Luther King’s contributions to American history, he is often placed in the moment of his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at the head of a march, or perhaps just off to the side at the signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Most known for his nonviolent philosophy and peaceful protest approach, students are often introduced to King in these bite-sized moments. When we only learn about one phase or achievement of a person’s life it leaves us with an incomplete picture. The Learning Lab collection Martin Luther King: The Later Years (1965-1968), created by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, provides a window to explore the last major campaigns in which King was actively involved.

King’s nonviolent approach to securing civil rights was rooted in love and designed to uplift all humanity. Often portrayed as the long-suffering and infinitely patient voice in the fight for civil rights, in the early years, King fought against discrimination in public accommodations and voting rights. The year after the Voting Rights Act passed, King wrote what would become his final book, entitled Where Do We Go From Here?, in which King expressed strong messages regarding his thoughts about race in America, poverty and his opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam. As he continued his work, King would fight against housing discrimination in Chicago, protest for better working conditions for laborers in Memphis, and lay the foundation for another large-scale demonstration in the nation’s capital to bring attention to the effects of poverty in the U.S.

When we study the issues and concerns that King raised in his later years, such as the lack of economic justice affecting Americans of all groups in the Poor People’s Campaign, students gain a fuller picture of King’s thinking about the issues that challenged America in his time. Seeing and understanding the multi-layered views that King held, helps students and ourselves navigate the issues that we face in our time.

Analyzing Artists’ Perspectives and Responses to King’s Legacy

One way for students to explore King’s legacy over time is through the lens of visual art. Many American artists have responded to King in the decades since his death, and analyzing the multiple perspectives represented by their artworks can help students explore our evolving national memory of the civil rights leader. A Learning Lab collection published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum features six diverse artworks made between 1968 and 1996 that each address King’s life and ongoing impact.

The earliest pieces in the collection capture the raw grief felt by many in the immediate aftermath of King’s assassination, from a deeply emotional wood carving by Daniel Pressley titled The Soprano at the Mourning Easter Wake of 1968 to Sam Gilliam’s hauntingly beautiful abstract painting April 4.

Later artworks remind us that despite his current status as a beloved icon of racial progress, King was a polarizing political figure during his life. After the establishment of a federal holiday honoring King in the 1980s, artist William T. Wiley created an etching that includes the seemingly tongue-in-cheek caption, “once you’re gone you’re ok, they give you a day.”

In 1995, Alfredo Jaar manipulated a famous Gordon Parks photograph of King’s funeral procession to highlight the disparity between the number of Black and white mourners present. Jaar’s piece, Life Magazine, April 19, 1968, models critical analysis of a historical document for students and could be paired with present-day photographs of racial justice demonstrations to extend the discussion.

The collection is rounded out with works by Loïs Mailou Jones and L’Merchie Frazier that both utilize collage-like techniques to reflect on King’s impact. Jones’s 1988 watercolor connects King to celebrated contemporary Black figures in politics, sports, and entertainment, whereas Frazier’s intricate quilt incorporates historical documents, from newspaper clippings and photographs of King to excerpts from his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

This diverse collection of artworks offers a unique way for students to examine King’s legacy through an interdisciplinary, inquiry-based lens.

Building Pathways to Civic Action Emulating King’s Work

Martin Luther King Jr. was known for his words, but also for his timing and discernment. He knew when to use his words to inspire communities, but he also knew when to listen, observing those around him quietly. How do we honor his legacy?

We begin with a day. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was a holiday enacted by former President Ronald Reagan in 1983. The observation of the third Monday of January was chosen because Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday is on January 15. Schools and federal agencies are closed, and many businesses offer their employees the opportunity of a day of service in lieu of a regular workday. But why stop with one day, when we can make our classrooms into civic spaces every day of the year?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/2f/ff2ff115-4b35-4073-ae86-5a23a1fe1448/nmah-et2015-15081-000001.jpg)

In education, we emphasize the importance of a strong foundation, scaffolding learning as scholars move through each grade. We model this in a Learning Lab collection created by the National Museum of American History, beginning with an introduction to Dr. King’s story and practicing careful observational skills with our earliest learners, and slowly moving towards critical thinking and action-oriented steps with older students. And we model this in ourselves, by speaking out in the face of injustice; by creating space for other voices to be heard; by looking for opportunities to act in service to others; and by remembering the histories of our collective past. Dr. King was a great man, but he was also an ordinary person who made history by taking action to better the world, and we, like him, have the same ability to do so.

Federal holidays and heritage months can serve as reminders to develop students’ inquiry skills. Introducing the C3 inquiry arc and taking informed action at an early age will support civic participation as students grow up. You might collectively consider: What is one thing you and your students can do this year to honor Martin Luther King Jr.?

The analysis and deep discussion of these primary sources and artworks can serve as a springboard for students to consider their own roles as changemakers within their communities. How might we center discussion and action around ongoing issues of racial and economic justice? What lessons will resonate today and into the future?

Editor's note: This article was originally published on January 7th, 2022 and has been updated with new links to relevant educational resources.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/e5/f4e5cc5c-93a4-4a53-bc29-942e50fed17a/the_soprano_at_the_mourning_easter_wake_of_1968.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c8/4f/c84f45e6-0d06-44da-8883-5cd630fff96f/saam-1973115_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/22/c422aab2-c7fc-4ef1-a529-72c904a74340/dr_king.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/a3/ffa3bad4-56ed-4089-82c4-9ef7aff16b98/we_shall_overcome.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/ee/24eea600-dbac-4f2f-8986-0d2feecf0563/saam-201339a-c_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/cb/79cbc311-d4bf-4d16-9850-2ce5542dab44/from_a_birmingham_jail_mlk.png)