SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

A Catalan Opera Adapts Greek Myth to Understand the Refugee Crisis

Since 1993, 33,293 people have drowned in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic trying to reach a safe place to start a new life.

:focal(600x400:601x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/aa/e0/aae0f6d7-2e8a-4b5e-81fd-38e364cda8b0/monster-in-the-maze-stage.jpeg)

In the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, a young hero from Athens resolves to put an end to the cruel demands of the Cretan king Minos. After defeating Athens, Minos had decreed that every year, a group of young people from the city would sacrifice themselves to feed the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull monster that lives in the labyrinth of his palace. Theseus sails to Crete determined to end this sentence by killing the Minotaur.

It’s a story that has been told for thousands of years. But when the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona’s opera hall, decided to undertake its own operatic retelling in 2019, called The Monster in the Maze (or El monstre al laberint), it took on a new and harrowing meaning.

“The link between the stage and the social and political reality that surrounds us is fundamental for me,” stage director and set designer Paco Azorín says. “So when one reads an opera about a people who have to take a boat across the sea and go somewhere else to fight a monster, the metaphor that emerges quickly brings us to the present situation in the Mediterranean Sea. In this case, we can talk about all the people who have to cross the sea in a tiny boat in hopes of finding a safe future in Europe.”

Since 1993, 33,293 people have drowned in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic trying to reach a safe place to start a new life. The boats leave without enough fuel to cover the distance between the ports of departure and arrival, and once adrift in international waters, they are lucky if they are rescued. Since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in early 2020, the journey has been even more difficult and dangerous.

In 2019, the Liceu began to prepare The Monster in the Maze in Barcelona with an adapted score, translation into Catalan by Marc Rosich, and new staging by Azorín. Conductor Simon Rattle commissioned writers Jonathan Dove and Alasdair Middleton to adapt the story for a participatory opera (which includes non-professional musicians) so that it could be semi-staged (performed without a set or costumes) with the Stiftung Berliner Philharmoniker, the London Symphony Orchestra, and at the Lyrics Arts Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

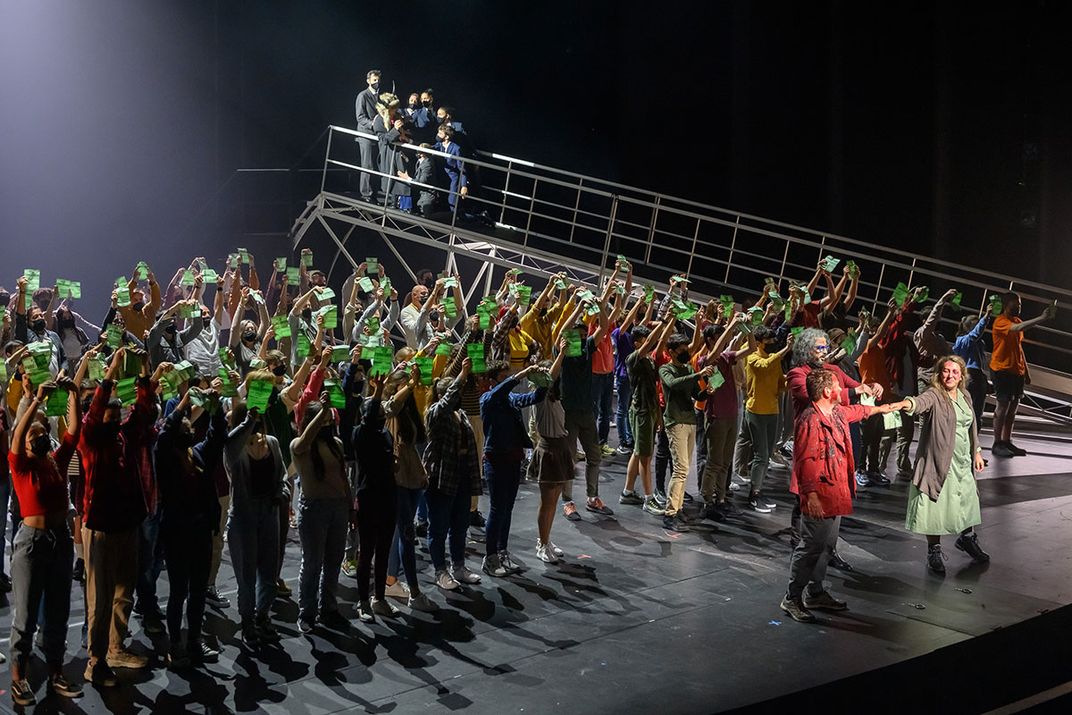

From the outset, the LiceuLearns organizing team wanted the project to be transformative for its performers. Over the course of four shows, six hundred twelve- to eighteen-year-old singers from twenty different high schools in Catalonia, plus the Liceu Conservatory’s youth orchestra, the Bruckner Choir, and the Coral Càrmina, sang in the contemporary rendition.

LiceuLearns also collaborated with Proactiva Open Arms, a nonprofit based in Badalona that has rescued more than 62,000 people at sea since 2015. When they proposed the partnership and recontextualization to founder Òscar Camps, the idea seemed magical to him.

“On the one hand, I really liked that the Liceu opened its doors to young people, because they are the future, and it is a powerful stage to do this from,” Camps explains energetically, waiting for a medical appointment before his next mission. “On the other hand, it seemed extraordinary to me that the Liceu wanted to explain our story. It felt good, even though our story is not the important one. The one that matters is the one of the people we rescue.”

Every day, people leave their homes and families in search of stable income and governments. Along the way, they are vulnerable to hunger, exposure, sexual violence, and human trafficking. Yet they are not deterred from attempting the journey.

“Often, the life they have where they come from is not a life,” Camps continues. “Once they are safe in our boats, the women sing. One starts, and the rest join in with her. The men pray, cry, and give thanks.”

On March 10, 2020, after finishing one of their final rehearsals, the musicians who were to perform in the premiere of The Monster in the Maze at the Liceu were informed that all of the scheduled performances had just been canceled. The COVID-19 pandemic had reached Catalonia.

Such uncertainty is the daily reality of the people who make a migratory journey, and, to some extent, the Open Arms team. So in April 2020, when its ships were denied permission to sail and one hundred and fifty elderly people were dying every day in Catalonia, Open Arms created a COVID volunteer brigade on the orders of Dr. Clotet and Dr. Mitjà of the Hospital Germans Trias of Badalona. The volunteer-run organization received more than 3,000 applications a week, offered 120,000 COVID tests in nursing homes, opened care centers for farmworkers, and assisted with the vaccination campaign.

Despite the lockdowns in many parts of the world, including Europe, the migratory flows from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean did not stop during the first wave of COVID. As Camps explains, the African continent deals with multiple ongoing pandemics—Ebola, AIDS, typhoid, tuberculosis—so daily life did not come to a halt as it did in other regions of the world.

“COVID just makes everything more complex,” Camps says. “We had to figure out how to apply COVID protocols on board our ships. With 200 or 300 people being rescued in a single mission, we have to organize clean and dirty areas. When we move someone from one to the other, we have to put on PPE as if we were entering the ICU. Then, for fifteen days, whether we have any positives or not, we quarantine while anchored outside the harbor. Sometimes we run out of food. It seems like administrations want to slow us down, but we have to solve every challenge.”

This same decisive attitude was cultivated by LiceuLearns. The young singers, dismayed by the cancelations after months of rehearsals, learned the value of perseverance. The production team found ways to safely adapt the stage and schedules.

“We sang masked, we staggered rehearsals, we minimized time in common spaces,” explains Antoni Pallès, director of the Liceu’s Musical, Educational and Social Project. “But, as always in an opera, every member of the team was absolutely necessary. We needed each other more than ever.”

While the initial metaphor for explaining the myth through the epic journey of refugees and the work of Proactiva Open Arms remained, for director Azorín and his team, the monsters kept multiplying.

“The staging adapted to the measures as they changed every week,” Pallès recalls. “For instance, the Athenians were supposed to be on a boat on stage, but the boat did not allow us to social distancing, so Azorín reimagined the possibilities. The Athenians were to be on stage, and a boat was going to be shown on screen. It was very effective and suggestive.” While difficult, he believes the process improved the final rendering of the myth.

Although it was somewhat strange at first, the members of Open Arms were closely involved in the educational aspect of the production. As Camps says, “The kids worked so hard. They watched all our videos. We wanted to convey that there are always monsters lurking—and we have to face them. It’s like when you run into a shark in the ocean. You can’t turn your back on it. You have to stare at it and punch it as hard as you can on the nose if you want to stand a chance. If you start swimming, trying to get away from it, you’ll die. You can’t turn your back on monsters, because then you become an accomplice of the monster itself.”

On April 24, 2021, The Monster in the Maze finally premiered at the Gran Teatre del Liceu. Unwilling to let the waves of the pandemic stop them from sharing their understanding of how this ancient story speaks to the present, the team was finally able to share it with its audience.

*****

Returning to the Liceu after so many months of lockdown, but this time with COVID measures in place, makes the experience of the premiere a curious mix of normal and strange for those of us in attendance. As always, we show our tickets to get in, but our entrance times are staggered. Someone takes our temperature, and we have to rub our hands with sanitizer. Due to seating capacity limits, only half of the 2,292 seats in the giant theater are occupied.

Everything is a bit different, no doubt, but the families that keep arriving in my area, all dressed nicely, don’t seem to notice. They look for and greet each other as if they hadn’t just seen each other on Les Rambles, the tree-lined avenue in front of the theater, just a few minutes prior, gesturing exaggeratedly to point out their assigned seats.

“My daughter told me they’re going to be on that side of the stage,” says a woman, lowering her mask so that another can hear her. An usher reminds them both that they must keep their masks covering both mouth and nose, and that they should stay in their seats. The usher repeats this reminder time and time again, apparently without losing patience. A lot of pictures are taken and shared immediately on social media, causing lots of emotions. In short, everything seems to be the same despite the theater being half full, because the day is not about statistics but about conquered challenges.

The lights dim and a voice asks us to turn off our mobile devices. Unexpectedly, the voice continues, making the strange normal yet again. It informs us that Roger Padullés, the tenor, has gotten hurt during the dress rehearsal. He’s not in great shape but has decided to sing anyway. The performance has not yet begun when the singers, musicians, and spectators come together in a heartfelt applause to celebrate the singer’s tenacity.

The lights go out, and in a flickering video projected on the screen on stage, the climate activist Greta Thunberg tells us: “You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I’m one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you! How dare you …”

After a solemn silence, flashing lights and the sound of a helicopter fill the theater. Armed men protect the arrival of the representative of the first world, Minos. In the stands, the children’s choirs move in their seats, keeping a safe distance, but with the body language of acute panic and uncertainty. Minos delivers his sentence on the Athenians while bells and percussion fill the pauses in his decree. A fence is raised while armed men threaten the Athenians as the judgement is passed. It is a world filled with frightening violence.

Theseus, who has just returned to his city, believes he can stop this injustice. The future of Athens is in jeopardy if every year a whole generation of young people must be sacrificed to feed a monster. Theseus’s mother, confused and alarmed, begs her son not to embark on this impossible journey. Theseus is not afraid, however, and sets sail, leaving his mother on her knees. The boat rocks gently at first. Then, suddenly and violently, they all fall into the sea.

At this point, the young people who have drowned rise up, one by one, and tell us their story—embodying not mythical characters but real survivors.

“My name is Adama. I am twenty-five years old, and I am the son of Guinean refugees. I left my country in 2012 but did not arrive in Tarifa until June 2018. After crossing the sea ...”

In December 2020, amid the pandemic, more than eighty million people were displaced worldwide. Eighty million people navigating uncertainty without a home. It’s a figure too large grasp. With every one of the stories rising up above the waters, we are reminded that behind every number within this incomprehensible figure, there is a person who left her country out of necessity, with reduced means, and that with her first step she lost her sense of human connection and community. When the maze of the sea swallows her up, she becomes merely a number because those who remember who she was, what she liked to eat the most, or what made her laugh, are not there to honor her.

Once in Crete, the Minotaur sniffs the young, fresh meat inside the maze. Most young Athenians do not dare enter, but Theseus does not hesitate. Theseus hears Daedalus, the engineer of the maze who lives permanently hidden and in fear inside his own complex, and persuades him to help. With his aid, Theseus kills the Minotaur.

When all the choirs unite on stage behind the victorious Theseus, they are exhausted as if they have been walking for years misunderstood, racialized, and rejected. The message from choreographer Carlos Martos to the performers is well rooted: “There are millions of people in diaspora walking around the planet, half of whom are women and children, and when they reach a border, despite the fact that they have no food or water, certain countries prevent them from walking any further. This is the function of the monster we have created. There is a monster—the first world—and it is this world that we must change.”

After an hour and a half of gripping the arms of my chair, the curtains fall and I rise with the other spectators. We applaud as the performers take an exhausted but satisfied bow. The last ones to take the stage are the high school teachers who long ago registered their respective classes for this transformative opera experience. When they do, the teenagers applaud and do the wave.

In the last performance of The Monster in the Maze, the last of the 2020–21 season, Òscar Camps took the stage to congratulate the performers. All the teens and adults rushed to take pictures with him, claiming they wanted a picture with Theseus. “This gesture told us we had touched something deep,” Pallès says, obviously moved by their affection.

*****

This rendering of The Monster in the Maze has not changed reality. Some 3.6 million Syrians live in refugee camps in Turkey awaiting entry permits to Europe. In Lesbos, the Moria Camp welcomes 5,000 people annually—and now after the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan, probably more. On the evening of August 2, 2021, after rescuing 400 people in twelve days, the Astral, the Proactiva Open Arms ship, came into port in Barcelona after its eighty-third mission.

The 4,400 spectators at the Liceu had 4,400 different reasons to attend the four performances, but unknowingly they entered a universe of moral counting. As the minutes passed, we realized that colonialism did not come to an end with the emancipation of the colonized nations. Colonialism continues, long after the centuries of expropriation of labor and resources, as so many young people of these nations now feel that the only way to secure a future is to flee.

Resituating stories like The Monster in the Maze in the current context makes us reconsider our position as a colonial nation. It makes us think that reparation and compensation start by admitting that the discourses of structural racism can be deconstructed as they were constructed, because narratives have the power to build new ways of giving meaning to the world. This is the potential capacity of a performance.

Many centuries ago, professional narrators were also magicians and healers, which ought not to surprise us. A well-interpreted narrative sorts out priorities. It strengthens relationships, makes fear fade, and thus has the power to heal. An interpretation that highlights the perseverance of the characters, that transforms every opportunity for change into an enriching moment to grow, that celebrates teachers and weaves new symbolisms has the power to bring new narrative structures into existence. This is exactly what happened for the 600 high school student performers and for the audience of the Gran Teatre del Liceu.

Meritxell Martín i Pardo is the lead researcher of the SomVallBas project and research associate at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She has a degree in philosophy from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a doctorate in religious studies from the University of Virginia.