NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Live Jellyfish Make a Splash in Marine Education

Smithsonian’s AquaRoom helps scientists learn more about these animals’ lives and educate future generations about their marine neighbors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Light_blue_transparent_jellyfish_on_black_background_with_tentacles_spread_out.jpg)

The ocean holds incredible biodiversity like vibrantly colored sea slugs and blue-green algae with biomedical potential. But some of these creatures, like jellyfish, have a second home. It’s called the AquaRoom and its the brainchild of invertebrate zoologists at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

“We’re always looking at these living animals and their biomechanics and trying to understand what they are like,” said Allen Collins, marine biologist, curator in invertebrate zoology at the museum and a NOAA Fisheries research zoologist.

Collins and his colleagues have been raising sea creatures behind the scenes in the AquaRoom for several years. They’re doing so to learn more about these animals’ lives and to educate future generations about their marine neighbors.

“It's about giving people the confidence to do science and interact with scientists and, then, to also bring the science from the lab to the public,” said Cheryl Ames, a marine invertebrate zoologist at the museum and co-founder of the AquaRoom.

A stinging reputation

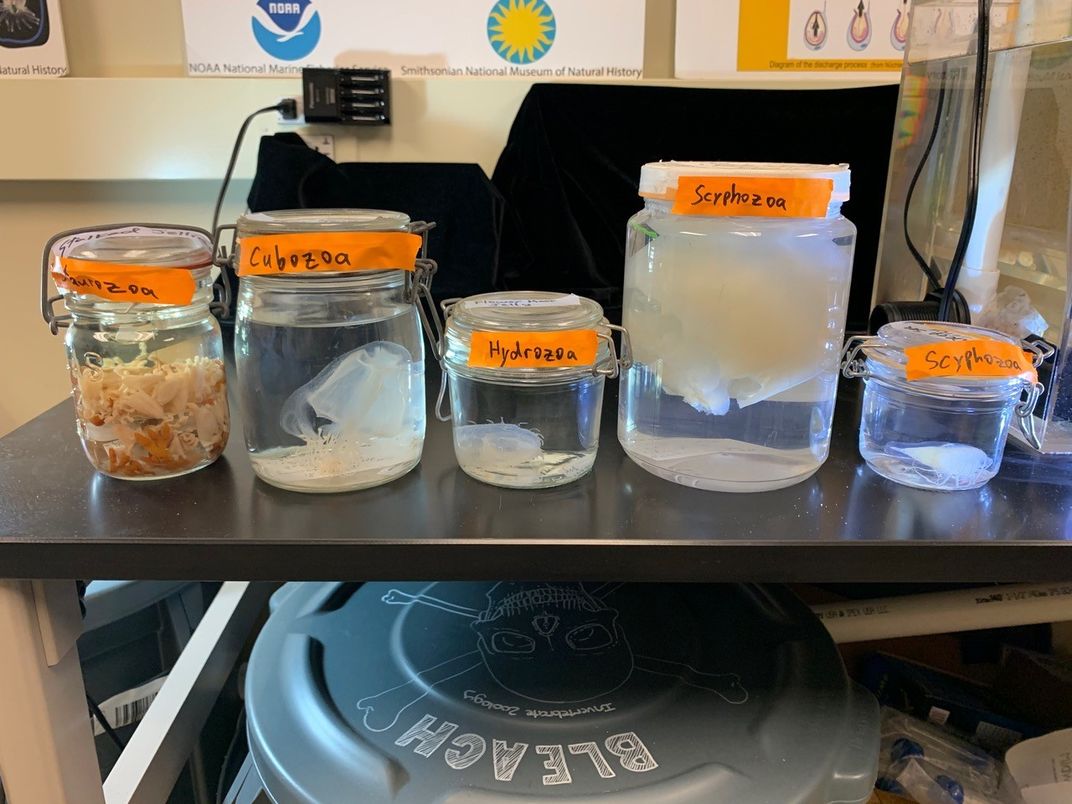

Over the years, people have studied and nurtured many species of marine invertebrates in the invertebrate zoology department’s AquaRoom. But Collins and Ames focus on cultivating jellyfish.

“There’s all sorts of variations across jellyfish species, so I focus on their life cycles and their diversity when showing them to people,” said Collins.

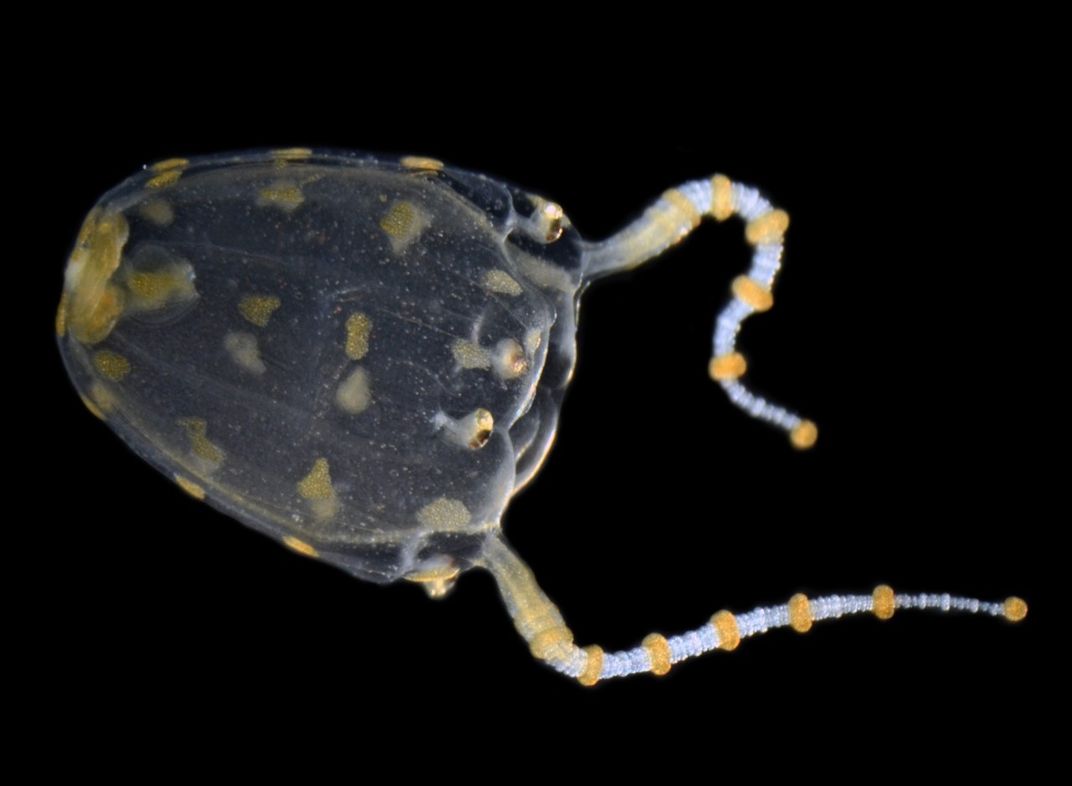

Jellyfish and their similarly translucent, fleshy counterparts, comb jellies, are mostly made up of water. But while the two look somewhat alike, jellyfish are closer relatives to corals, some of which have equally impressive stings.

“Getting stung is often what people think of when they encounter Jellyfish,” said Collins. “But most of them won’t harm you and they have important roles in ecosystems as predators and prey.”

The DIY AquaRoom

Breaking jellyfishes’ stinging stereotype is one of the reasons why Collins and Ames founded the AquaRoom with the support of the invertebrate zoology department over half a decade ago.

“We had a room but didn’t have any gear,” said Collins. “So, Cheryl and I started collecting freebie aquarium stuff that people were getting rid of in the department, including a 55-gallon tank.”

That 55-gallon tank now holds many young jellyfish, called polyps, which attach onto surfaces until they grow into their free-floating forms. Before the pandemic, high school and undergraduate interns and adult volunteers cared for the growing youngsters.

“It’s a door for people to come into the museum and do outreach and learn more about the animals by interacting with them and caring for them,” said Collins.

The department gave tours to interested future scientists, bringing them beyond the exhibits into the museum’s research area. They’ve also brought live jellyfish to the museum floor to show visitors interested in jellyfish evolution and conservation.

“We've used the animals in many ways, like bringing them down to Q?rius and setting up microscopes that people can look in,” said Ames.

Jellyfish for education

Although the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History was closed for the past year, the AquaRoom continued to be an active site for learning and outreach with virtual webinars that highlighted the living collections.

“No matter what age group I’m trying to reach, I always want to make studying invertebrate marine animals seem like something people can do if they want to,” said Collins.

Recently, Collins spoke online with members of the Young Scientist Academy in North Carolina about jellyfish polyps he sent them. These students have been growing the polyps for their own experiments like studying jellyfishes’ preferred habitats.

“This event was for young kids and a lot of the young kids didn’t have a lot of access to science,” said Collins. “It was natural fit for our work.”

Now that the museum is reopening soon, the AquaRoom’s future could one day include a return to in-person programing and a whole new wave of internships.

“It has been and will be a really fun place to do research, because it’s different from the rest of the museum.” said Collins.

Related stories:

DNA Makes Waves in the Fight to Save Coral Reefs

Scientists Find Blue-Green Algae Chemical with Cancer Fighting Potential

Get to Know the Scientist Discovering Deep-Sea Squids

How Scientists Learn What Lives in the Deep Ocean

Can Technology Bring the Deep-Sea to You?