NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Five of Nature’s Best Beards for World Beard Day

Humans aren’t the only bearded beasts. In the sea, the sky and the land between, organisms sport bristles, fuzz and fur of all styles. Instead of splitting hairs over what type of beard is best, here are five of nature’s finest.

:focal(396x248:397x249)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Three_people_holding_the_worlds_longest_beard..jpg)

People get attached to their beards. So much so, that this Saturday is World Beard Day — a day just for celebrating facial hair of all shapes, colors and sizes.

But humans aren’t the only bearded beasts. In the sea, the sky and the land between, organisms sport bristles, fuzz and fur of all styles. Instead of splitting hairs over what type of beard is best, here are five of nature’s finest.

The world’s longest beard

North Dakota farmer Hans Langseth had an unusual postmortem wish: he wanted his beard cut off and saved. He started growing it at the age of 19, and at 17 feet and 6 inches long, Langseth’s beard was crowned the longest in the world by the Guinness Book of World Records. To keep from tripping over it, he would reportedly roll the hair around a corncob and tuck it into a pouch or pocket.

After his death in 1927, his children fulfilled his wish and saved the beard. Not knowing what to do with the odd heirloom, Langseth’s son eventually donated it to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in 1967.

Researchers at the Smithsonian can use human hair to learn about a person’s diet, health and even exposure to pollutants. Langseth’s beard is unique in that its length and debris found in it provides a sort of timeline for his life. For example, Langseth harvested wheat as a young man, and a few small kernels are still tangled throughout the sections of hair that he grew early in his adult life.

Bearded vultures

Bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) are named for the black bristles beneath their beaks, but beards are hardly their most distinguishing characteristic. These birds paint their plumage a rusty orange color using iron-rich soil to show age and status. And their wingspans can exceed nine feet.

Bearded vultures are also known as lammergeiers, which means “lamb-vulture” in German. But despite their fearsome name and appearance, they rarely attack live animals. Instead, they search for carcasses and pick out bones. The scavengers drop femurs and other large bones onto rocks from hundreds of feet in the air to shatter them into digestible pieces. They are the only bird known to subsist almost entirely on bone and bone marrow.

Bearded fireworms

The bearded fireworm (Hermodice carunculata) is named for the hollow, white bristles that line its body. These bristles are filled with a neurotoxin that burns and irritates skin if touched.

The worms are native to the tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. They live on reefs, rocks, sand — even drifting wood — and eat corals, anemones and small crustaceans. Though brightly-colored all the time, bearded fireworms really shine during mating, when the females emit a greenish glow to attract mates.

Bearded irises

The bearded iris (Iris germanica) gets its name from the row of fuzz near the base of the petals. These “beards” might help attract pollinators like bees. The sun-loving, vibrant purple flowers bloom in late spring and early summer, and although native to the Mediterranean, they can be found throughout Europe and North America.

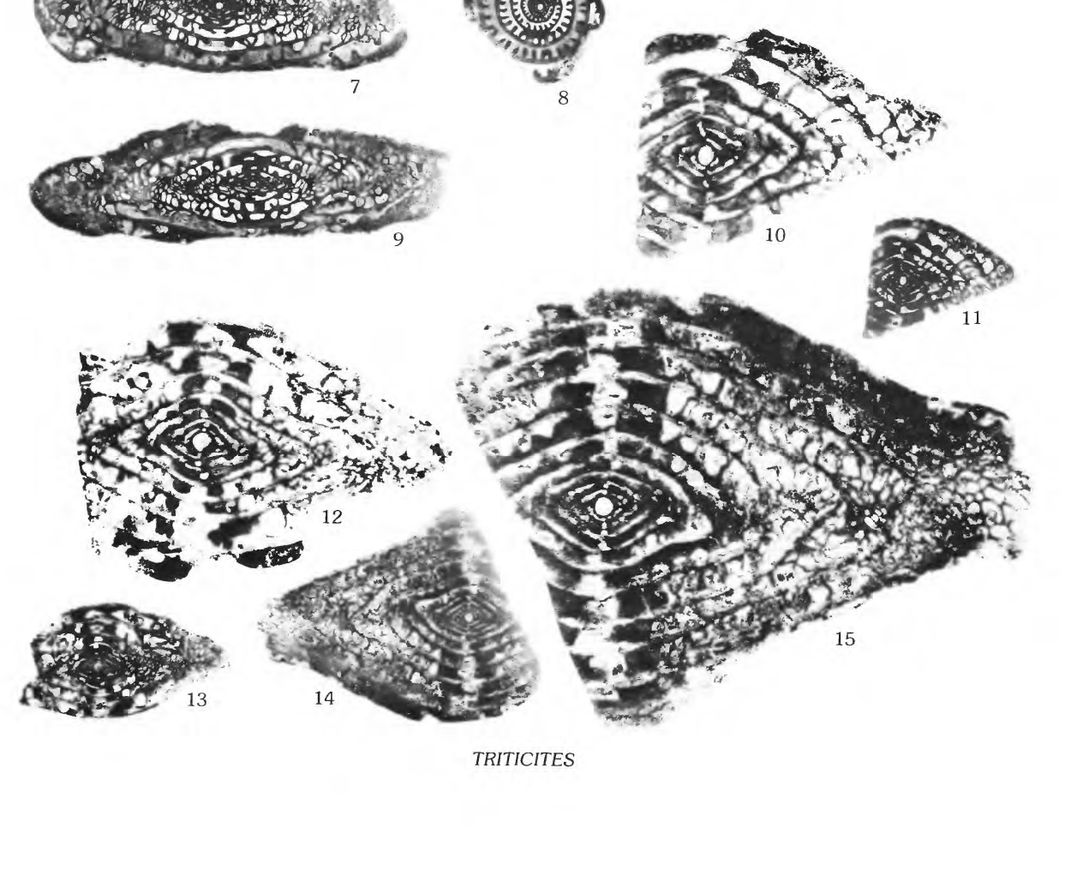

T. Beardi fossils

This fossil’s beard is in its name. Triticites beardi was named for the man who first collected it: John Beard. T. beardi is a species of extinct fusulinid — single-celled, shell-building marine organisms. Researchers have found fusulinid fossils on every continent except Antarctica, but T. beardi has only been seen in Kentucky.

The intricate fossils of these tiny organisms help scientists determine when and how rocks formed. Rocks that contain T. beardi, for example, are typically around 300 million years old.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History has the T. beardi holotype — the individual specimen that scientists used to describe the species.

Related Stories:

Five Species to Wrap Up Invasive Species Week

Six Bewtiching Smithsonian Specimens to Get You Ready for Halloween

Five Things You Shouldn't Miss in the New Fossil Hall

Check Out These Unexpected Connections in Natural and Presidential History

10 Popular Scientific Discoveries from 2019