NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Notorious Asian Giant Hornet Finds Home in Smithsonian

Here’s why the invasive Asian giant hornet’s identification is actually a scientific success story.

:focal(668x353:669x354)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/An_insent_on_a_gray_background.jpg)

The Asian giant hornet is having a bad month. In early May, newspapers reported on a sighting of the non-native hornet in Washington last December. The Washington State Department of Agriculture identified the insect and sent it to the United States Department of Agriculture where Matt Buffington, a research entomologist at the Systematic Entomology Laboratory, confirmed its identity. He then placed it in the National Insect Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History for further study.

As media coverage grew, this species soon gained the unfortunate nickname ‘murder hornet,’ stirring fears of a killer bug attack.

But the Asian giant hornet’s identification is actually a scientific success story. It represents how entomologists at the Smithsonian and USDA work together every day, curating millions of insect specimens for research at the United States National Insect Collection and protecting the United States against potentially invasive species that threaten its agriculture and economy.

The buzz about the hornet

Invasive species are non-native species that can disrupt ecosystems and the economy. Entomologists recognized that if these hornets were able to establish a foothold on the West Coast, they could harm honeybee colonies across the country which are “responsible for one in every three bites of food we take and increase our nation’s crop values each year by more than $15 billion,” according to the USDA. In short, without action, the Asian giant hornet could become an invasive species.

“Invasive species are a serious threat to United States agriculture. But I do believe calling the Asian giant hornet a ‘murder’ hornet is inappropriate. I think that's completely wrong,” Buffington said, “It’s very doubtful that these insects will kill humans.”

News coverage of the insect led to a frenzy of social media posts about how killer bugs were coming to the United States. As a result, people began killing other species of stinging insects.

“There’s already a tendency for people to be afraid of insects, especially stinging insects, even though they're not dangerous to the vast majority of people,” Chris Looney, a research entomologist at the Washington State Department of Agriculture, said. “That’s kind of a bummer because they fill all these vital ecosystem roles. Even if this does become an established species, it’s not likely to emerge as an enormous human health threat.” He was part of the team that made the initial hornet identification.

Identifying the invader

When state officials recognize a potential invasive species, they call in the USDA to confirm the species’ identity. The specimen travels to the Taxonomic Services unit of the Agricultural Research Service, and in many cases on to the National Museum of Natural History’s National Insect Collection, where USDA research entomologists, like Matt Buffington, examine it.

Buffington compared the North American specimen to other specimens in the National Insect Collection. It matched the other Asian giant hornet specimens from Asia, confirming Washington State’s earlier identification.

“With all the great technology that’s now available, there’s still no replacement for an actual specimen that represents a species,” Buffington said.

Buffington then added the first identified United States Asian giant hornet to the National Insect Collection, because the hornet could provide useful data for entomologists, like how the species appeared on the West Coast.

An age-old partnership

The partnership between the Museum and the USDA began back in 1881, when Spencer Baird, at the Smithsonian, and Charles Valentine Riley, of the USDA, agreed to have the collection owned by Smithsonian and maintained by USDA.

“We essentially pay rent to the Smithsonian by doing the best we can to help take care of their collection. And we take that responsibility very seriously,” Buffington said. “Without the collection, our lab can’t function.”

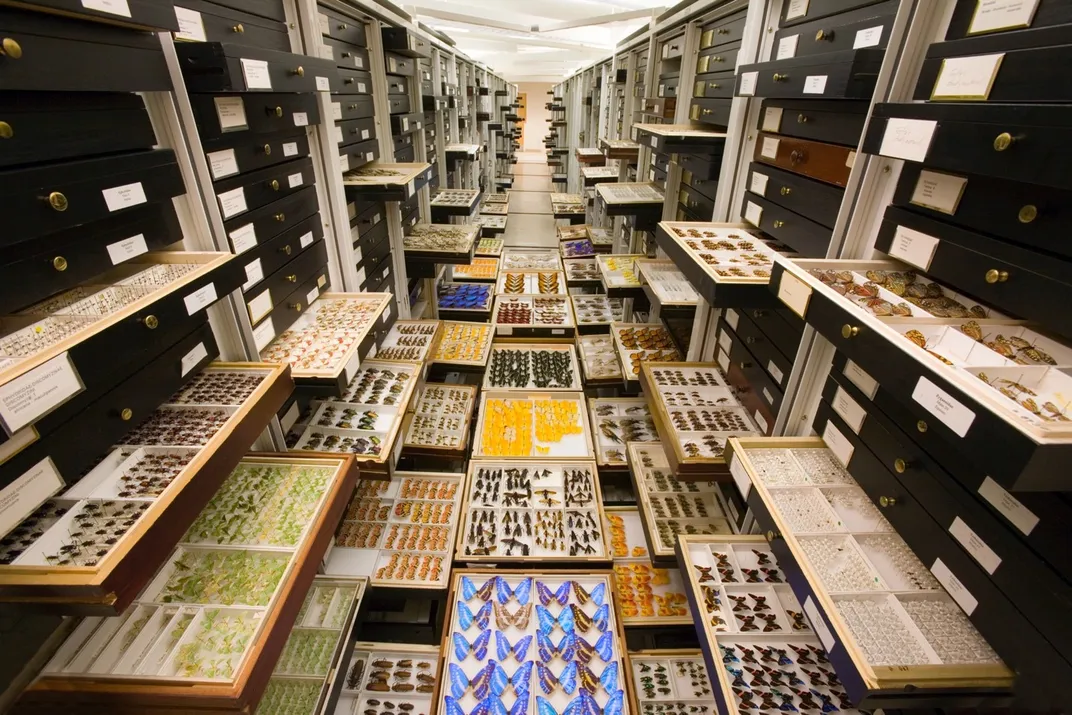

The collection now holds over 35 million specimens housed in three locations: the National Museum of Natural History, the USDA Agricultural Research Center, and the Smithsonian Museum Support Center.

A real and virtual insect database

Insect enthusiasts and entomophobes alike can see the entire Vespa collection and in particular, the Asian giant hornet, online on Smithsonian Open Access. The collection is constantly being updated by the team of entomologists at the National Museum of Natural History and the USDA, who recognize the value in maintaining an active, evolving collection.

“The National Insect Collection is a dynamic database of insect species across the US and the world,” Buffington said. “Without it, entomologists would have no reference point to identify new invasive threats and anticipate the risks that come with them."

Related stories:

Five Species to Wrap Up Invasive Species Week

Digitization Allows Public Access to Smithsonian’s Hidden Collections