NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Convergence May Help Scientists Predict the Future

Archaeologists J.Daniel Rogers and Wendy Cegielski identified three distinct research trends that need to converge to address today’s greatest challenges.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/ExcavatedLaptop6_CegielskiEtchings.JPG)

Can we use the past to predict the future? We already do, but we can do much better.

We are archaeologists and we obsess about time. Before we ask any other research questions, we ask “when?” We develop chronologies about everything from ancient farmers in Spain to the empires of central Asia. But archaeology isn’t just about keeping events in order anymore. Sure, we want to interpret and give voice to things that happened in the ancient and recent past, but there are new methods for studying the past. Of these new approaches, we’ve identified three distinct trends that need to converge to address today’s greatest challenges: scientists working across disciplines, the use of massive data sets, and use of increasingly advanced computer methods.

First, diverse disciplines need to work together. We should bring our best thinking to address the greatest challenges, from poverty and inequality to climate change, in a kind of total science way often called convergence. We say we are archaeologists, but we also try to embody the interdisciplinary approach by working in computer science, economics, demography, materials science, and data management. We also routinely work with other scholars ranging from historians to political scientists. It doesn’t make any sense to us that so many disciplines independently study similar topics and seldom share their findings with each other. The good news is that universities are taking the interdisciplinary challenge seriously and a new generation of professors and researchers see working across disciplines as the norm, not the exception.

Next, research in all fields generates massive quantities of information. Unfortunately, most of this information is not standardized and is accessible only to those who developed it. Fortunately, a large number of initiatives are underway to compile all kinds of information in more accessible ways. These are the “big data” projects. Museums, like the Smithsonian, are one of the original big data projects. They have collected and preserved information for centuries through artifacts, specimens, and archival documents. Museums have initiatives in bioinformatics and data accessibility, but—so far—results are scattered and inconsistent. We have a long way to go.

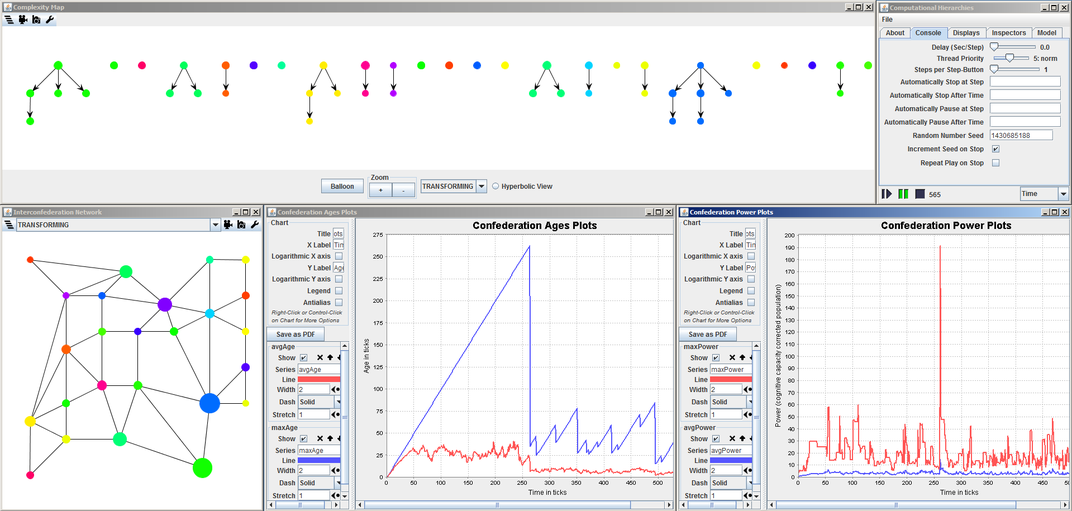

There’s also a new generation of sophisticated computational methods that gives science the tool kit to make the above approach happen. A good example of how to combine interdisciplinarity, big data, and computers is a kind of research that uses agent-based simulations. Think of it as SimCity on steroids. Agent-based modelers usually create artificial humans that “live” and make decisions like real humans. We then put them on a simulated landscape and start the clock. At the end of the simulation, we collect the data and compare it to information about the real world. With each run of the simulation, it’s easy to make very small adjustments and test many different hypotheses. We are often amazed by how important small changes are when played out over long periods of time. Understanding the role of small changes will lead to important breakthroughs in solving today’s problems.

We already use the past to predict the future but in a limited capacity. For example, if we are driving along a street and come to a red light, we can reasonably predict based on past experiences that it will soon turn green and we can go on our way. The more distant future, however, is harder to predict—especially if it is not in our daily lives. That is why the holy grail of science is solid prediction and explanatory insight. Agent-based models can be used in a forward looking way by taking past and current conditions, applying a change, and simulating the future.

Many people believe that the past, whether recent or ancient, was so different from our modern world that it offers few relevant answers. In this perspective lessons from the past are often viewed as nothing more than interesting anecdotes. We see more than just stories. In fact, we see opportunities for archaeology and all forms of humanistic and scientific research to play roles in working together. Our crystal ball is a bit hazy, but it is more reasonable to make meaningful predictions with more disciplines working together, better use of lots of data, and more computer simulations and other quantitative approaches. This is the future of the past.

To learn more about the computer simulations, take a look at our recent (2017) opinion in the Proceedings of the U. S. National Academy of Sciences.