The Aeronauts Brings the Bravado of Balloon Flight to the Big Screen (Artistic License Included)

The new film The Aeronauts truly captures the excitement of ballooning in the 19th century, even if it makes a few historical errors along the way. Ballooning expert Tom Paone explores the history behind the film.

:focal(730x1267:731x1268)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Artboard_1_copy-2.jpg)

The new film The Aeronauts, released December 6, 2019, by Amazon Studios, is the first in a long time that features a lighter-than-air flight that doesn’t involve either a fiery explosion over Lakehurst, New Jersey, or a terrorist attack on the Super Bowl. It does, however, truly capture the excitement of ballooning in the 19th century, even if it makes a few historical errors along the way.

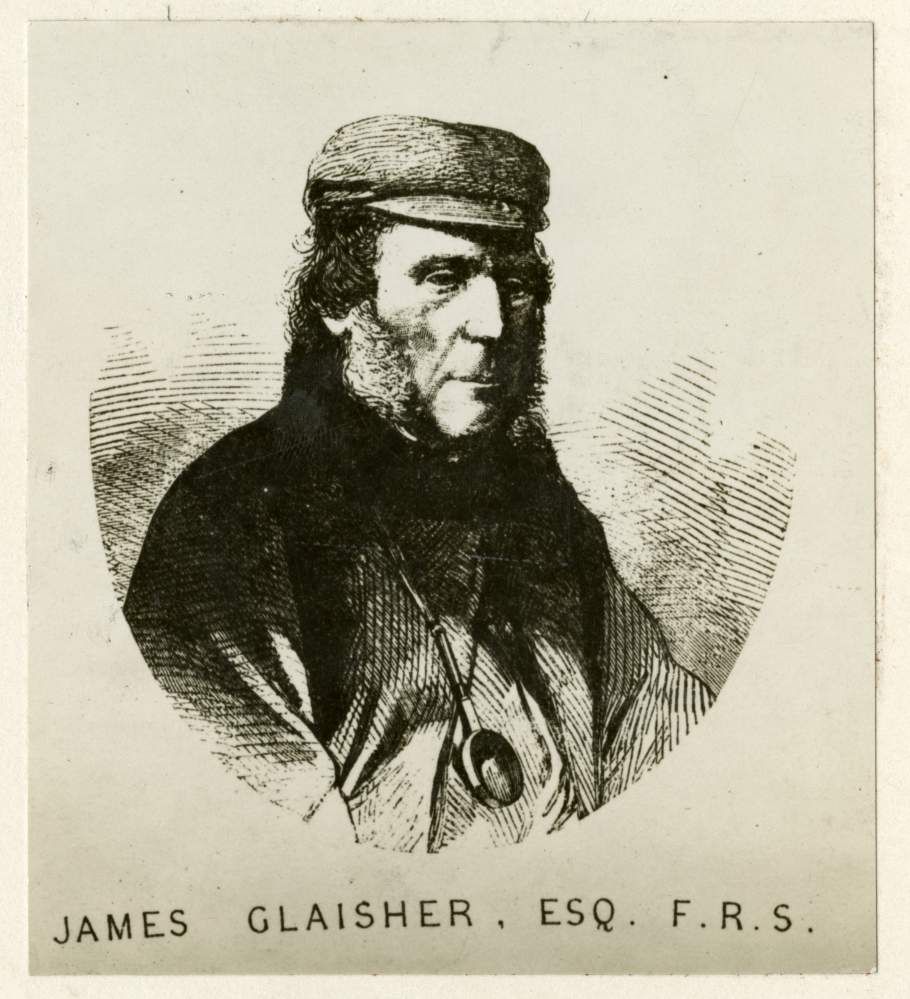

The film follows the September 5, 1862, balloon flight of James Glaisher, whose work at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, focused on the fields of meteorology and magnetism. Glaisher became interested in balloons after he observed several flights of spectacle in England and realized that balloon flights could be excellent platforms for scientific research. Starting in July 1862, at the age of 53, Glaisher conducted scientific experiments aboard several flights in balloons in order to gain a better understanding of how temperature, dew point, and other weather-related factors changed with altitude. Glaisher published an account of his scientific balloon ascensions under the title, Travels in the Air (London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1871).

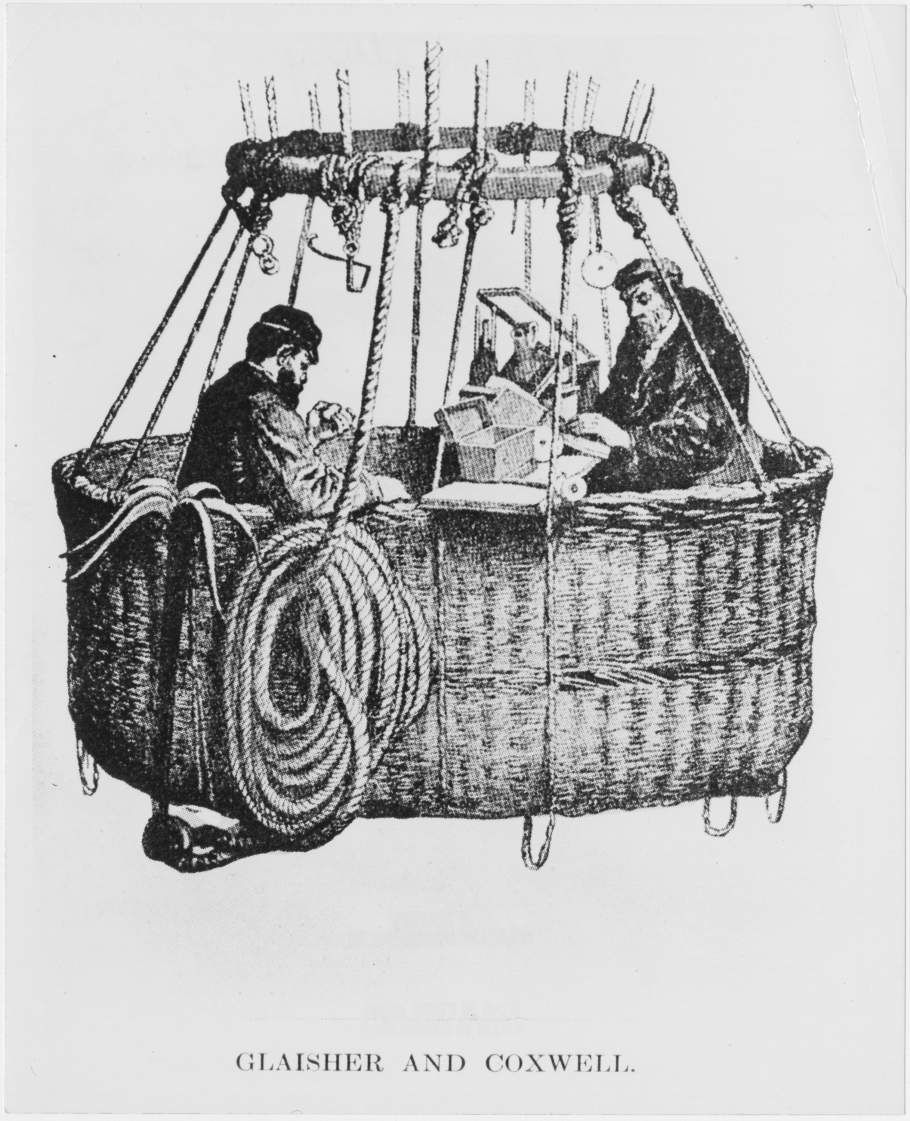

In the book, he described many aspects of the flight showcased in the film. He detailed the more than two dozen instruments brought on the flights to record the hundreds of observations he would take at altitude. The book even describes the work station he created, similar to the one shown in the film, explaining: “All the instruments were attached to the table with strings, which could be cut immediately, or they merely rested on stands which were screwed to the table. The table was fixed across the car, and tied there by strong cord. On approaching the earth, all the instruments were rapidly removed and placed, anyhow, in a basket furnished with a number of soft cushions to comer them in layers…” (pg. 41).

The balloon used by Glaisher during the September flight was actually piloted by Henry T. Coxwell, an accomplished English balloonist of the time. Glaisher worked with Coxwell to acquire a new balloon to assist with the flights. He described the process in his book, stating, “On the 30th of June, 1862, Mr. Coxwell brought his new balloon to Wolverhampton; it was not made of silk, but of American cloth, a material possessed of a great strength. Its capacity was 90,000 cubic feet, exceeding in size that of the famous Nassau balloon” (pg. 42).

In the film, James Glaisher, portrayed by Eddie Redmayne, seeks the assistance of balloonist Amelia Wren, portrayed by Felicity Jones. Although Wren added a great dimension to the film, the character is actually a fictionalized combination of several historical figures from the time period. Although this was artistic license, the character of Amelia Wren does help bring to light real-life female balloonists.

One of the most famous female pilots during the early days of ballooning was Marie-Madeleine-Sophie Armant Blanchard, more commonly known as Sophie Blanchard or Madame Blanchard. She started her career alongside her husband, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, an early French balloonist who made dozens of flights. He died in 1809 shortly after suffering a heart attack during a balloon flight (a loss similar to one suffered by Amelia Wren in the film). Following his death, Sophie Blanchard started on a solo career, entertaining crowds throughout France with lights and fireworks launched from her small balloon. She even impressed Napoleon Bonaparte with her flights, and he made her an official entertainer of his court. The high-risk crowd thrilling flights which made Madame Blanchard so famous, however, would eventually take her life. In 1819, Sophie Blanchard was killed when one of her fireworks set her balloon on fire, causing her to fall to her death.

The September 1862 flight portrayed in the film became one of Glaisher’s most well-known flights, due to the extreme elevation he reached and the safe return to Earth of both Glaisher and Coxwell. Many aspects of the flight are accurately displayed in the film. Glaisher did bring six pigeons with him so that messages could be sent from the balloon. He mentions in his writings that “…a third was thrown out between four and five miles, and it fell downwards as a stone” (pg. 57).

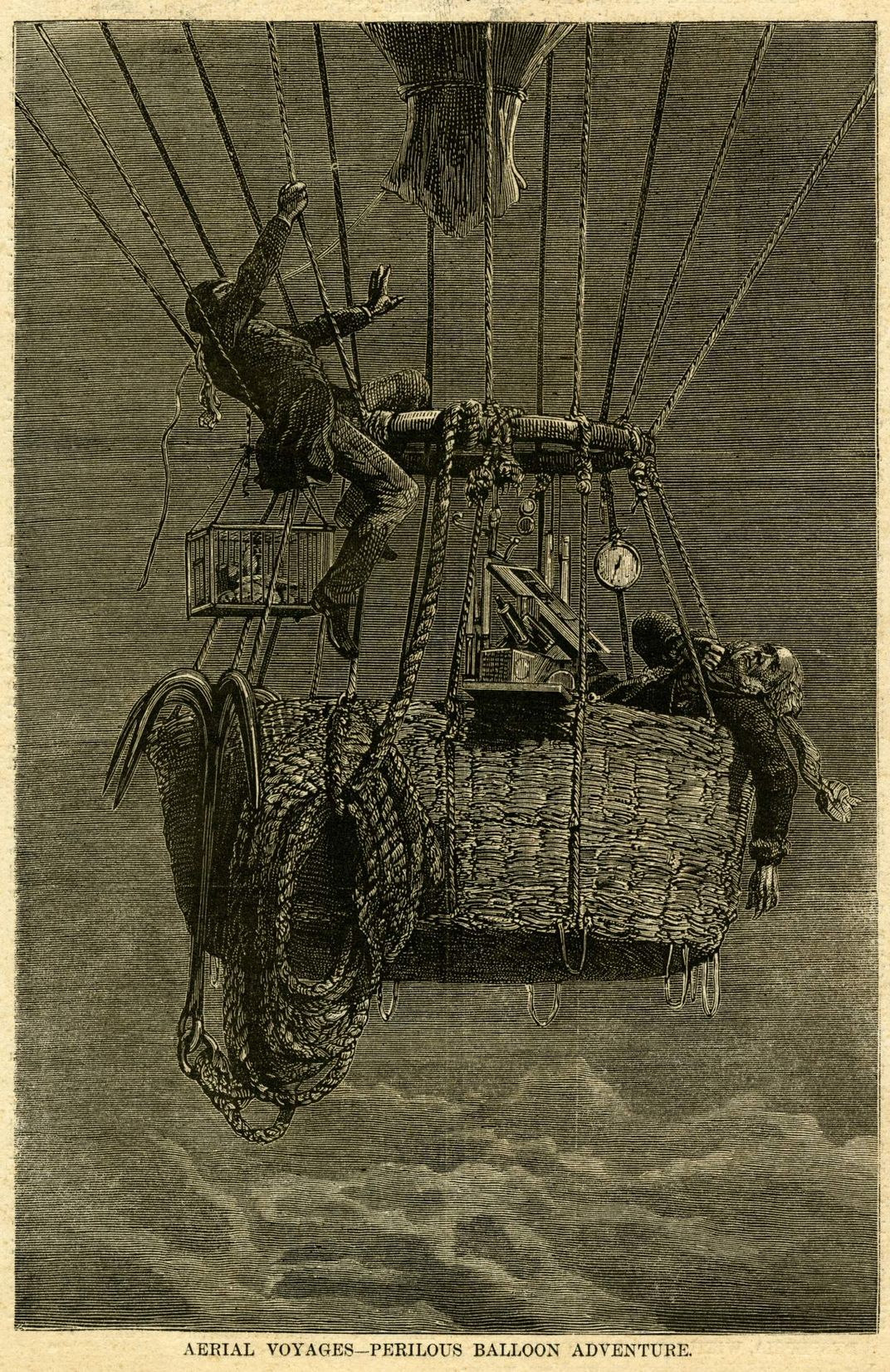

Glaisher also gives an incredibly detailed account of the near-death experience he and Coxwell experienced as they reached an altitude near 30,000 feet, which is also portrayed in the film. He wrote that, shortly after reaching a height of 29,000 feet:

“…I laid my arm upon the table, possessed of its full vigor, but on being desirous of using it I found it powerless-it must have lost its power momentarily; trying to move the other arm, I found it powerless also. Then I tried to shake myself, and succeeded, but I seemed to have no limbs. In looking at the barometer my head fell over my left shoulder; I struggled and shook my body again, but could not move my arms. Getting my head upright for an instant only, it fell on my right shoulder; then I fell backwards, my back resting against the side of the car and my head on the edge. In this position my eyes were directed to Mr. Coxwell in the ring. When I shook my body I seemed to have full power over the muscles of the back, and considerably so over those of the neck, but none over either my arms or legs….I dimly saw Mr. Coxwell, and endeavored to speak, but could not….I cannot tell anything of the sense of hearing, as no sound reaches the air to break the perfect stillness and silence of the regions between six and seven miles above the earth” (pg. 53).

Glaisher was suffering from hypoxia, or a lack of oxygen, as a result of the low levels of oxygen available at such a high altitude. The flight also suffered a near catastrophe when a tangled line meant that Henry Coxwell could not open the valve to release gas from the balloon so they could begin their descent. Although Coxwell’s actions to remedy the situation were different from those of Amelia Wren in the film, Glaisher does describe the actions Coxwell took to save them both: “Mr. Coxwell told me that while in the ring [the ring is where the lines of the balloon are attached to the lines from the balloon basket] he felt it piercingly cold, that hoarfrost was all around the neck of the balloon, and that on attempting to leave the ring he found his hands frozen. He had, therefore, to place his arms on the ring and drop down… He wished to approach me, but could not; and when he felt insensibility coming over him too, he became anxious to open the valve. But in consequence of having lost the use of his hands he could not do this; ultimately he succeeded, by seizing the cord with his teeth, and dipping his head two or three times, until the balloon took a decided turn downward” (pg. 54).

The flight of Glaisher and Coxwell reached a world record height of at least 30,000 feet that day and may have gone even higher. Glaisher reported that temperatures must have been around -50 degrees Fahrenheit according to some of the final measurements he made before passing out. The fact that Glaisher and Coxwell survived their ordeal is incredible, since later balloon flights in open balloon baskets to similar heights often led to death, like the final flight of Hawthorne C. Gray in 1927.

The Aeronauts is not a perfect historical account of the flights of James Glaisher and Henry Coxwell (especially since Coxwell is not mentioned in the film). The worst thing you can do, however, is bring a historian to a history movie. We can spot every small inaccuracy and spend 20 minutes explaining why it was inaccurate. We do, however, still love history movies.

What The Aeronauts does offer is a beautiful glimpse at the excitement that ballooning brought to the 19th century. From flights of entertainment like those of Madame Blanchard, to the flights of scientific discovery by Glaisher, balloons opened up a new world of possibilities. The movie has flaws, such as the omission of James Glaisher’s fabulous Victorian facial hair for a freshly shaven Eddie Redmayne, but it is visually stunning, and captures so much of what makes ballooning popular even to this day. If nothing else, this film will hopefully inspire you to learn more stories from the National Air and Space Museum’s lighter-than-air collection, like the balloon flight of Double Eagle II, featured on the covers of both National Geographic and Sports Illustrated or one of the highest hops in history from Red Bull Stratos.