Why Polaroid Inspired Both Steve Jobs and Andy Warhol

Beloved by innovators and artists alike, the camera company dissolved into history once it lost its beloved CEO. Apple should take note

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Polaroid-Chris-Bonanos-631.jpg)

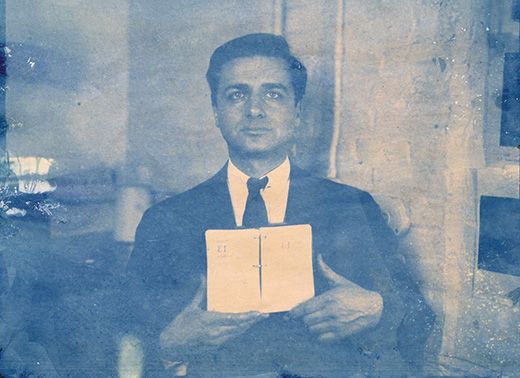

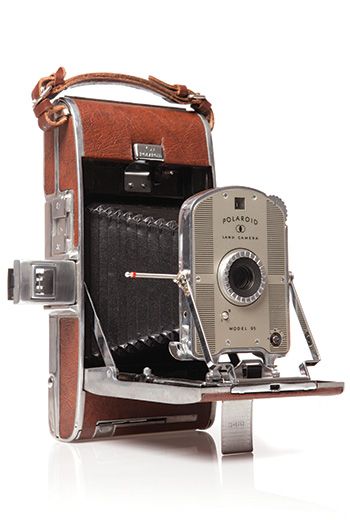

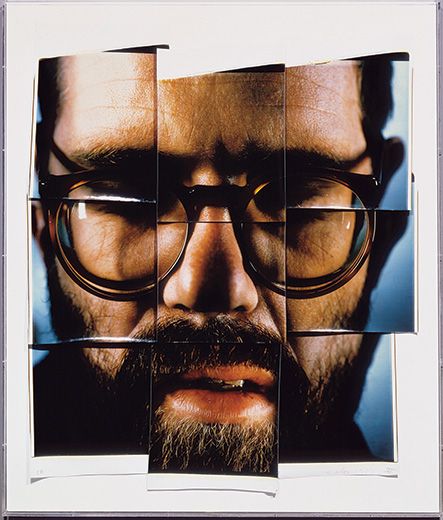

Few companies can claim they altered the path of an entire medium but that’s exactly what Polaroid did in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s to photography. Founded by Edwin H. Land in 1937, Polaroid was the Apple of its day and Land, the original Steve Jobs. The idea factory churned out iconic products such as the SX-70, the one-step instant camera that now resides in the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York City.

In his new book, “Instant: The Story of Polaroid,” Christopher Bonanos of New York chronicles the rise and fall of the company and details how it changed the way we save memories.

What made you want to write a book about Polaroid?

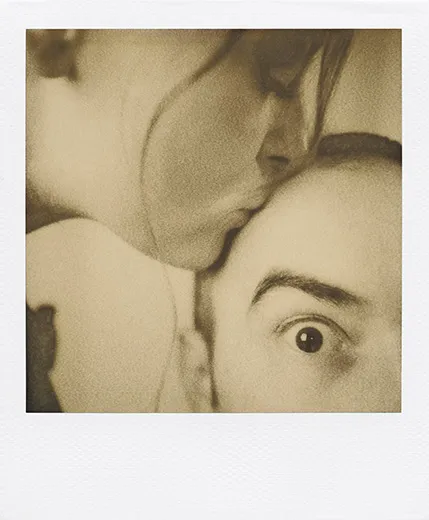

In 1983, when I was 14, I got my first camera, an old one from the ’50s that I bought in a junk shop. I started using it and there is something bewitching and strange about a picture you see right away. I used it on and off through college and beyond. Then in 2008, when Polaroid announced the very end of instant film production, there was a show going on at the Whitney [Museum of American Art] on Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids. I wrote a little story for New York about this sort of moment when the medium was going away but it was also being celebrated in fine arts. I called up a bunch of Polaroid artists, people like Chuck Close who work in Polaroid film, and they were really angry about having this material taken away from them. It led me to discover that there was a Polaroid cult out there of artists, enthusiasts and people who just love this old way of making pictures.

Your description of Edwin Land was reminiscent of Steve Jobs. In terms of innovation and design, was Polaroid the Apple of its day?

Land and Jobs were both just obsessed with making a product perfect. They both worked like crazy. They both really believed in locating a company at the spot where science and technology meet fine arts. And maybe most important of all they both felt that if you make a fantastic product that the world has never seen before, then the marketing and the selling will take care of itself. Land once said, “Marketing is what you do if your product is no good.”

Thirty years later they asked Jobs how much market research he was doing on whatever the Apple product was at the moment and he said, “We didn’t do any. None. It’s not the consumer’s job to know what he wants.” It’s the same philosophy. Land was one of Jobs’ first heroes and they met a few times in Cambridge. When Land was sort of nudged out of Polaroid and into retirement in 1982, Jobs was interviewed not too long after that and he said “That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard. This man is a national treasure.”

Land made some pretty remarkable predictions for the future. He predicted cell phone photography and Instagram.

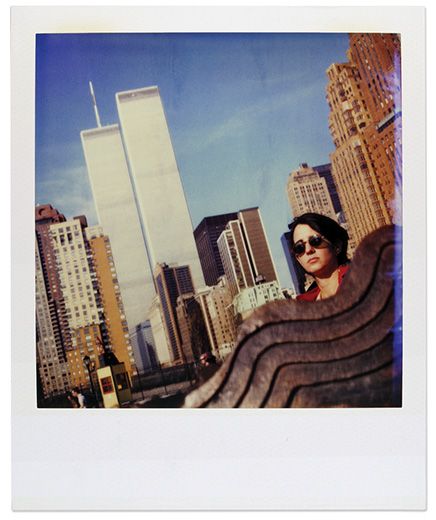

He may not have specifically seen exactly the device you have in your hand but he came pretty close. There’s a fantastic film of Land from 1970 where he’s explaining his vision of the future of photography as he saw it when he started the business in 1937. He said we’re a long way from a camera that will be like the telephone, something you use everyday like your pencil or your eyeglasses. Then what he does is he reaches into his breast pocket and he pulls out a wallet and he says, “It would be like a wallet” and the thing is black and about 7 inches long and 3 inches wide and he holds it up in front of his eyes vertically and it looks for all the world like he’s got a cell phone in his hand. Really, the thing he wanted was almost no impediment between the photographer and having the picture available to you. In the early days of Polaroid you had to pull-tabs and throw switches and things to make the processing procedure work, his goal all along had been, you click, it does everything and then you just see your picture. Effortless. A cell phone is about as close as you’re going to get to that.

Why did famous photographers such as Ansel Adams and Walker Evans like using Polaroids so much?

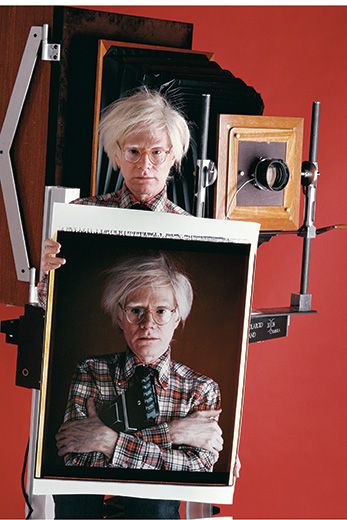

Different people liked it for different reasons. Adams loved Polaroid because he was such a technician in black and white that he could really see what he was doing on the spot. If he was hauling a camera up into Yellowstone on his back or in his station wagon, it was extremely valuable to him to be able to see a picture on the spot. Other people liked it for other reasons. Andy Warhol liked the intimacy and that you could see what you got right away. Other people were impatient especially when they were learning. Mapplethorpe learned to shoot with a Polaroid camera because he was both unwilling to wait for the lab and also because a lot of his photos were so explicit that it was not a good idea to send them to the lab.

What do you consider the most iconic photographs ever taken with a Polaroid?

The Warhol portraits that you see in galleries and museums all the time of Liza Minnelli and Elizabeth Taylor are based on those silk screens, which are in turn based on Polaroid photos he shot of all these people. That was his work process. He would take about 50 portraits of anybody he was going to do a painting of and work from those to make silk screens. There are also a number of the Ansel Adams landscapes of Northern California, the ones you see of Yosemite and other famous scenes, are often shot on large format professional-grade Polaroid film. There’s that one portrait “El Capitan Winter Sunrise” from 1968 that is like nothing else. It’s a fantastic demonstration of what you can do with the right camera and a sheet of Polaroid film.

Describe the rivalry between Kodak and Polaroid that resulted in the biggest settlement ever paid out.

They had this uneasy dance for most of their lives because Kodak was, in the beginning, Polaroid’s first big customer and for many years supplied certain components of Polaroid film. Then they sort of had a falling out in the late ’60s because Kodak realized that it had been supporting not a company that was complimentary to its business but somebody who was increasingly taking market share. Kodak had also heard the first inklings of SX-70, which was going to be a blockbuster if it worked, and they suddenly thought, “Are we giving away the game here?” When SX-70 came around Kodak had a big program going to produce its own instant camera and film, which came around four years later. In 1976, Kodak introduced its instant photography line. A week and a half later Polaroid sued them for patent infringement.

They spent 14-and-a-half years in court and when the settlement came in Polaroid vs. Kodak, Polaroid won. Kodak not only had to pay the largest fine ever paid out, which was nearly a billion dollars, but also had to buy back all those cameras. If you had a Kodak instant camera in the ’80s you got a letter saying Kodak will send you a check or a couple shares of stock. The total in the end was $925 million that Kodak had to pay Polaroid and it stood as the largest ever settlement paid out in a patent case until last month when Samsung was ordered to pay Apple $1.049 billion in damages. [Samsung is appealing the decision.]

Land felt as though Kodak had come along with a clumsier, less elegant version of exactly what he’d done without advancing the game and he was a little offended. He once said, “I expected more of Eastman.” In Apple vs. Samsung, a great deal of what was driving things at the beginning was that Jobs was disgusted with Android for exactly the same reasons. It was precisely the same competitive instincts shot through with outrage at the mediocrity of it all.

What started the downfall of Polaroid?

There are a lot of different threads that sort of come together. It’s little stumbles that turn into a snowball effect. Land didn’t put a good successor in place or more accurately, he didn’t have a succession plan in place. His successors did something right and some things wrong but what was missing in the time after Land’s leadership was a big idea. They did a pretty good job of coming up with products that enhanced the technology they already had but they never quite figured out what the next thing was going to be. There were big research projects within Polaroid to work on digital cameras, to work on ink-jet printers and other technologies. A combination of conservatism and entrenched habits and a little fear of what the future without film would look like economically all snowballed together to sort of bind up the company in one business model that it had been building for a long time.

What is “The Impossible Project” and how do they hope to bring Polaroid back?

The current Polaroid is alive, they are trying to make interesting little products again. It’s a much smaller worldview than they once had.

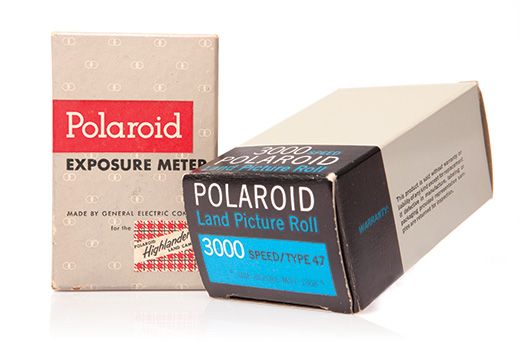

Then there is “The Impossible Project,” which when Polaroid quit the film business in 2008, Dr. Florian Kaps, André Bosman and Marwan Saba dived in and bought the tooling in the very last factory before it was torn down. They have spent a couple of years trying to make film and, when they introduced it in 2010, it was definitely a beta test. First generation film was very problematic. They weren’t able to use the old formulas because they couldn’t get the chemicals anymore, those companies went out of business. Each batch since then has gotten better and last month they introduced the first film that actually behaves like Polaroid 600 film did. It looks like it’s supposed to. It’s easy to shoot and it is marvelous. They really finally got it to where it need to be.