What it Took to Create the World’s First Gay Art Museum

Charles Leslie’s passionate half-century of homoerotic art collecting offers a mirror for the history of gay history itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/6f/516f4882-799b-4e2d-be03-00eac926cb32/2014_qthreads06-.jpg)

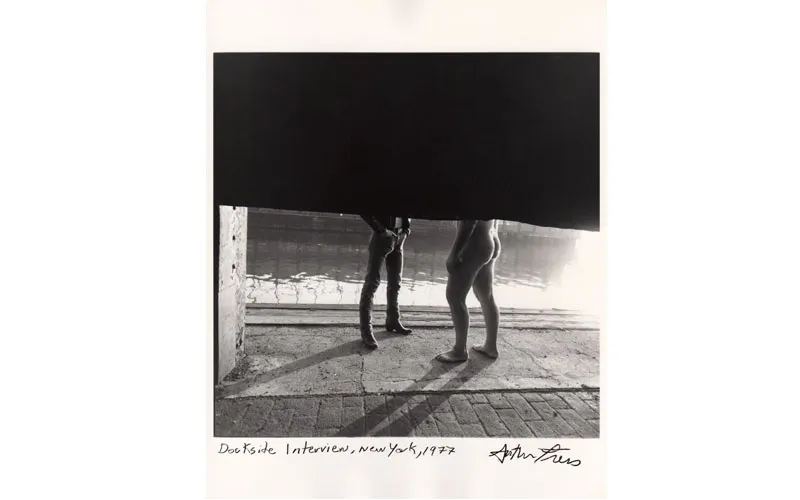

Man of the hour Charles Leslie was resplendent in a metallic gold jacket and a pair of hot pink leather shoes. From the stage of the Founders’ Day celebration of the Leslie + Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, the octogenarian art collector addressed the raucous crowd there to celebrate the upcoming expansion of the museum he established– a major milestone that will double in size the world’s first and only museum dedicated to gay art. But before discussing the future, Leslie wanted to talk about the origins of his collection of homoerotic work.

Speaking self-referentially, Leslie says, “If your family had an Encyclopedia Britannica in the house in the 1930s,” recalling his own childhood in Deadwood, South Dakota, “you discovered Greco-Roman sculpture. And the rest was history.”

The rest, indeed, was history: thousands of years of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender history, ignored and relegated to circumscribed footnotes, if that. Until very recently, these stories occupied no chapters in textbooks or wall space in our museums. But thanks to pioneers like Leslie, that’s changing. In many ways, Leslie’s life can be seen as a mirror for broader societal trends in LGBTQ history keeping. Or as the president of the museum’s board of directors, art historian Jonathan David Katz, puts it, Leslie “encapsulates the cultural tendencies” of more than half a century of gay historic activism.

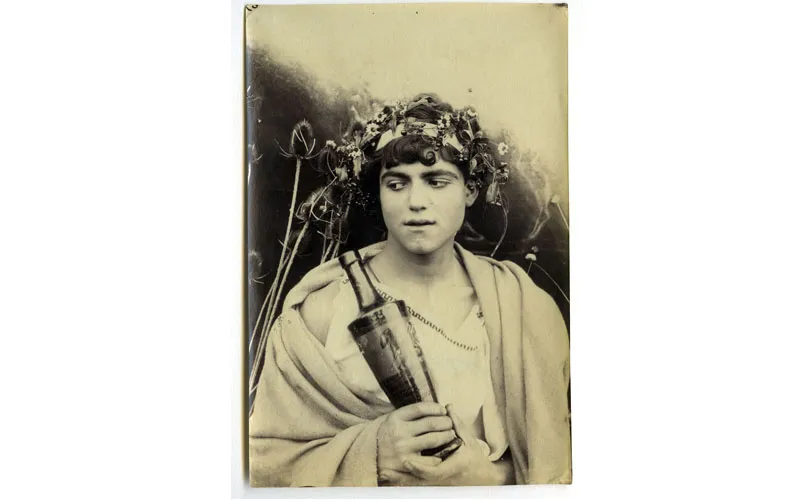

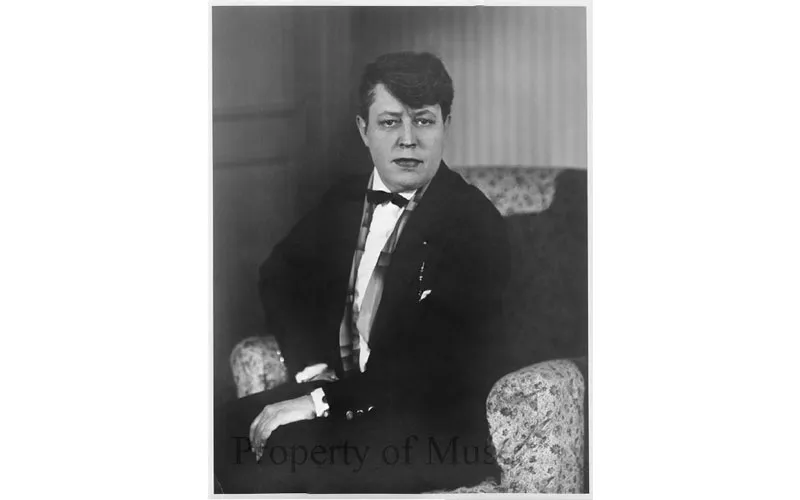

Leslie’s historical awakening began when he was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany, during the Korean War, where he first encountered the work of pioneering sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. Before the rise of Hitler, Hirschfeld helped to turn Berlin into a haven for sexual minorities, with the opening of his Institute for Sexual Research in 1919.

“I never knew there was such a person,” Leslie exclaimed, still struck breathless some 60 years after he first discovered Hirschfeld. “Such a movement!”

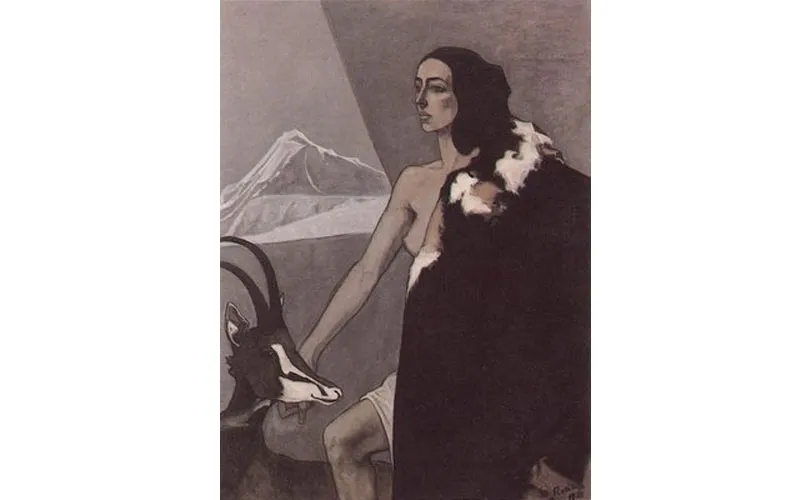

After the war, Leslie toured Europe with the Lotte Goslar Pantomime Circus for a few years before enrolling in the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill. As it did for many men of the time, Europe introduced Leslie to a more open vision of gay life. Growing up in a small town during the Depression, Leslie’s exposure to gayness as an identity was limited to what he could glean from the encyclopedia. Aware of his own sexual desires from an early age, he left for Los Angeles as soon as he could, where he easily fell in with its sub rosa gay community. But it was Europe that made him realize there was such a thing as “gay history” – and that much of that history was only preserved in art. Soon, he began secretly buying any such work he could find.

“I’d go to a flea market and find some little drawing or something that gave me a certain frisson,” he recalls, sitting in the Soho studio he’s had since 1968. “If I could afford it, I'd buy it.”

Upon Leslie’s return to the states, he joined the touring production of Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer. Eventually, he settled in Soho. At the time, the area was “an industrial slum,” says Leslie. His few neighbors were activists, outlaws and artists – those willing to risk illegal living in terrible conditions in return for huge spaces, few rules and low overhead. There, Leslie worked as a massage therapist, which is how he met the love of his life, interior decorator Fritz Lohman.

“We made the discovery early on that we'd both been discreet collectors of gay imagery,” Leslie says. Lohman was older, and an established designer to the rich and powerful, including Barbara Walters and the Onassis family.. His resources, combined with Leslie’s connections to the theater and art worlds, enabled them to amass a trove of gay art.

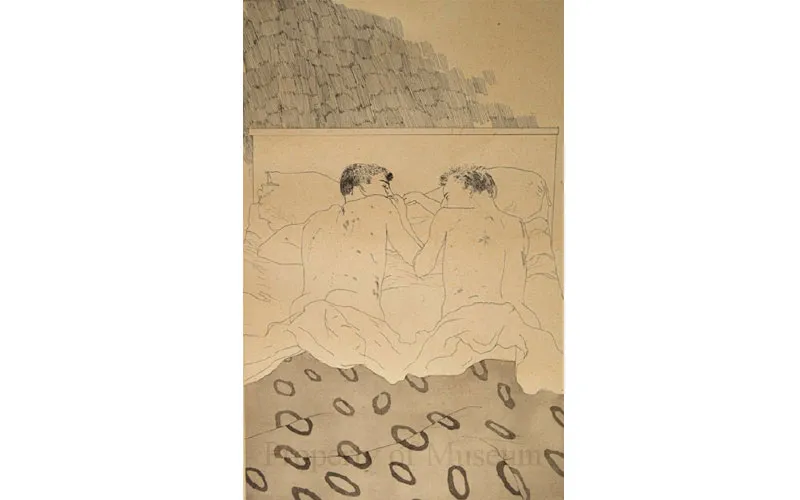

But what, exactly, makes art gay?

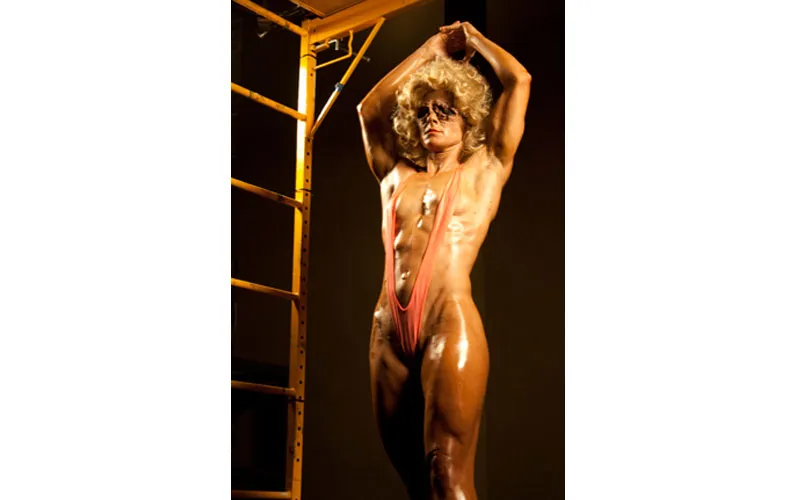

“Charles [Leslie] has always been fundamentally focused on the homoerotic, which he understands as the most dissident form of art making,” says Katz, “because by definition it has been historically excluded.” However, even Leslie understood that a work could trigger that certain frisson without necessarily being erotic. Does that leave “gay art” in the same nebulous I-know-it-when-I-see-it category as pornography or obscenity?

“Art doesn't have a sexual orientation. Art is art,” says Hunter O’Hanian, who has served as president of the museum since 2012. Eloquent, graying, and tattooed, O’Hanian is the perfect poster boy for an outlaw collection that’s infiltrated the mainstream. In his eyes, what makes a piece of art “gay” is the perspective and intention of the artist. We paint ourselves into our work, including our desires, and it is this perspective that queers the art. Katz, who also co-curated the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery’s controversial exhibition “Hide/Seek” in 2010, goes a step further, believing that “queer art can be made by straight people, because queerness is a social-historical identity category,” not a fixed behavior (which implies that queerness can and will look different in different times and cultures). Nevertheless, in the time during which Leslie was first collecting, the vast majority of gay work was made by gay artists.

Leslie’s patronage of that work extended far beyond simply collecting it. He quickly enmeshed himself in the fight to turn Soho into a live-work artists district, in order to protect the growing community of artists he’d discovered working there. Stephen Petrus (author of From Gritty to Chic: The Transformation of New York City’s Soho, 1962-1976) says that Leslie was “an unofficial leader” of the Soho Artists Alliance, which “was crucial to the zoning changes that legalized artist residency in Soho.”

Leslie would become lifelong friends with many of these artists, like painter Marion Pinto, whose full-sized nude portrait of Leslie and Lohman still hangs over Leslie’s couch. Many were gay, but kept that side of their art hidden. “Most people didn't want that stuff because what would you do with it?” Leslie says. “You couldn't show it, you couldn't hang it, and it had no market value because there was no market for it.” At least, there was no market for it yet – but Leslie, and the sexual and political revolutions of the ’60s and ’70s, would soon change that.

As he tells it, three things happened in the summer of 1969: Woodstock, the Stonewall Rebellion, and his first annual Exhibition of Homoerotic Art, which he held in his Soho studio.

“A la Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland,” Leslie laughs while remembering, “Fritz and I said ‘Hey, let's put on a show!’”

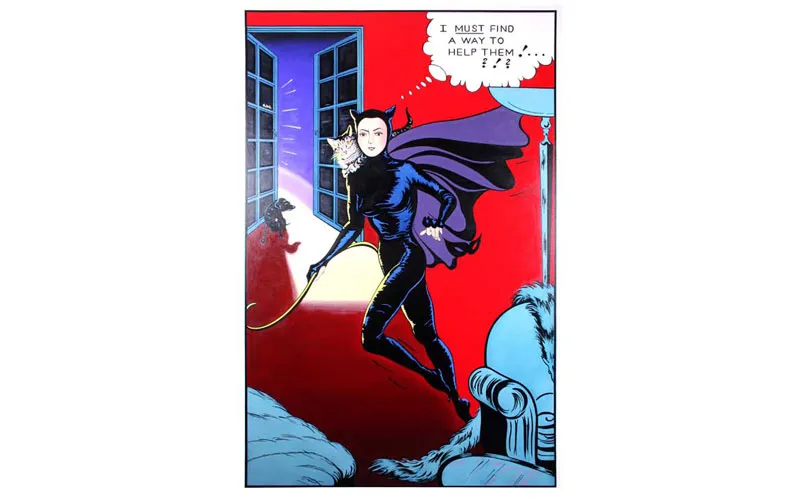

Their hope was to sell explicitly gay work (as opposed to work by gay artists trying to mask their sexuality or create art for a straight audience), in order to prove it “wasn’t pointless to make.” Leslie and Lohman invited a few dozen friends; Over the course of the weekend, more than 200 people showed up. After the third such Exhibition in 1972, they opened their first official gay art venture, The Leslie Lohman Gallery on Broome Street.

But before Soho blossomed into the white-hot center of New York City’s art world (by 1975, an astonishing 83 galleries had popped up), Leslie and Lohman presciently purchased a number of unwanted buildings. The income from these properties allowed them to collect work from around the world, while simultaneously maintaining their gallery space.

There, they continued to show homoerotic art (one early show introduced New York to the leather daddy aesthetic of Tom of Finland), but also branched out to include work by women (such as Marion Pinto’s solo exhibit “Man as a Sex Object”), and less openly erotic work. But the initial focus on gay men, and in particular, white gay men, continued the unfortunate tradition of excluding women and people of color from the historical record.

“For a long time I just really felt that it was a male space and it had very little women's stuff in it,” says Maxine Wolfe, one of the coordinators of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, which was founded in New York City the same year that Leslie opened his gallery. Much like Leslie and Lohman, the women who founded the LHA did so with a conscious political agenda and little reliance on formal training or mainstream institutions. “The whole idea was to do something that would be for the community and by the community,” Wolfe says, “because no one else was doing it.”

At the time, small groups of politically engaged LGBT people were forming collectives all around the country to support their communities from within, such as the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (a transgender rights and direct action group founded in New York City in 1970), and the Combahee River Collective (a black lesbian-feminist group formed in Boston in 1974). The Leslie Lohman Gallery fit right in with this newly radicalized ethos of claiming a public identity without assimilating or trying to play down their sexuality.

For a decade, the gallery operated on a thin margin of profitability, more as a labor of love than a commercial venture. But the early ’80s would see the business – and nearly the entirety of gay life in America – subsumed by the AIDS crisis. Many of their artists and customers died, while others refocused their energy on caring for the sick and fighting homophobic families, apathetic government organizations and corporations that saw the gay community as too small a market to make it profitable to explore new drugs.

“Within two years we lost 14 good friends,” Leslie says, remembering that difficult time. “Two of them died in our house because they had no place to go.”

They had to close the gallery in 1983, but continued to promote gay art by playing yenta to an informal network of artists and collectors. But by 1987 (the year the AIDS activist group ACT UP was founded), they were desperate to respond to the crisis in some way. Their accountant told them that the gallery, as a for-profit enterprise, was a non-starter. So instead, they opened the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to showing and preserving LGBT art.

In the beginning, they often got calls from the frantic friends and partners of recently deceased artists, who needed someone to rescue work that was being trashed by indifferent landlords or hostile families.

“A significant amount of our history was being destroyed,” says O’Hanian, the museum’s president. He credits Leslie, and his volunteers and staff, with saving many important works and adding to them to the museum’s growing collection, which today has more than 24,000 pieces.

For the next quarter-of-a-century, the foundation continued to develop shows aimed at the gay community. But over the course of the late ’90s and early ’00s, mainstream interest in this work began to grow, and they found themselves attracting larger and more diverse audiences. Art that had been literally unshowable just a few decades earlier was now (slowly, and not without controversy) being recognized as part of the modern canon. As the work has become more valued, so too has the institution. In a review of a recent show, New York Times art critic Holland Cotter praised the “dedicated labor of this invaluable museum” for bringing forward hidden parts of history.

That has included bringing forward the parts of history that the collection itself has downplayed, like work by women, transgendered artists, and people of color. O’Hanian sees the mission of the museum to be the preservation and promotion of art by “those who transcend some sense of binary-based gender or sexuality or orientation.” By bringing in diverse curators to oversee exhibitions, he tries to work against the limited perspective that always comes with being a small institution with a small staff. Wolfe says she believes the collection has gotten better and more complicated over the years. “I'm hoping that as they get bigger they'll be able to sustain it,” she adds.

In 2010, Fritz Lohman passed away at the age of 87, endowing the museum with his substantial estate (including his stake in the properties he and Leslie purchased in Soho), giving the institution freedom to launch shows largely unfettered by the demands of donors or grant-making institutions. With this security, they hope to, by next year, receive accreditation from the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York as a full-fledged museum. In 2011, they received a provisional charter, making them the first and only gay art museum in the world (the Schwules Museum in Berlin and the San Francisco GLBT History Museum preceded them, but both focus on history). Accreditation through the Alliance of American Museums may come further down the road, once the paperwork with the state is completed.

In just the three years that O’Hanian has been at the helm, museum attendance has nearly doubled, up to 25,000 visitors annually. In order to meet the demand, the museum is taking over the mattress store next door, which will provide an additional 3,000 square feet. of space, allowing them to put on as many as three exhibitions at a time. Construction will begin this fall, and they hope to have their first show in the new gallery some time in early 2016. “Ultimately, we will inhabit a dedicated building,” board president Katz predicts. But he expects the current expansion will provide adequate space for at least the next few years.

As for Leslie, he no longer leads the museum. Yet despite all the growth and change of the last half century, the spirit with which he founded the institution – a belief in the importance of LGBTQ art, on its own terms – still pervades the space.

When asked why he made this his life’s work, an answer comes quick to Leslie’s lips. “This is a part of human history that has been relentlessly destroyed, subdued and hidden,” he says. “Finally, the time has come to save it.”