What Defines Latino Literature?

In compiling the latest anthology in the Norton series, professor Ilan Stavans researched the themes explored by Latino authors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Latino-Literature-poet-Martin-Espada-631.jpg)

“Right now, being a Mexican in the United States is very scary,” says Ilan Stavans, Professor of Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and editor of the recently published Norton Anthology of Latino Literature. “You are often at the bottom of the scale, and there is a lot of animosity.” Literature, Stavans says, can help smooth interactions among the diverse ethnic groups and cultures in the country. The 2,700–page anthology, which includes 201 authors, arrives at a pertinent moment. According to recent census statistics, more than one out of every two people added to the U.S. population between 2008 and 2009 is Hispanic, and by 2050, the group will increase to 30 percent of the U.S. population. Stavans recently discussed with me the exhaustive project of assembling the collection and the evolving role of Latino culture in the United States.

Can you describe the genesis of the project?

The project started 13 years ago. By then, a number of Latino writers had crossed from the margins to center stage. There was a lot of interest in how people would articulate this new literature that was emerging. Would it be a literature of specific groups, for example, Puerto Rican literature or Cuban American literature? Or, was there one single river that had a number of tributaries? Henry Louis Gates, Jr. had just published The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, and I thought that it was time for something similar to be done with Latino writers. Latino literature has now consolidated its presence. It is clear that it is here to stay and that it is pushing the limits of its own conditions, with novelists of all sorts reaching beyond what I would described as Latinidad— or what it means to be Latino in the United States. In the last several decades, Latinos finally have been entering the middle class. This anthology not only explains the forces behind that economic move but justifies the move. It is a book that all middle-class Latinos need, proof that we’ve made it: We’ve arrived.

How did you and fellow editors decide to use the term “Latino” in the title instead of other appellations such as “Hispanic”?

Two prominent terms, “Latino” and “Hispanic,” refer to people living in the United States who have roots in Latin America, Spain, Mexico, South America, or Spanish-speaking Caribbean countries. “Hispanic” is a reference to Hispania, the name by which Spain was known in the Roman period, and there has always been strong ambivalence toward Spain in its former colonies. Hispanic was the term adopted by the government—by the Nixon government in particular— and that made the community feel it was being branded. The term “Latino” has emerged as more authentic, although it’s gender specific. In any case these two terms, at present, keep on fighting for space. Newspapers will sometimes use both in the same article as if editors chose not to choose. The anthology’s editorial team endorsed the community-preferred word and made that clear in the preface.

Given that so much of the material included in the collection is political or historical and not necessarily what we think of as literature, how did the editors define literature?

The anthology understands literature in a very open-ended fashion, not only short stories and poetry and novels, but memoirs and nonfiction books, logs and letters and types of music ranging from corridos [traditional Mexican ballads] to pop songs, also cartoons, comic strips, and jokes. We ended up endorsing “literature” as a written expression that conveys the search for identity. Historically, the 19th century is defined by annexations and internal turmoil. For instance, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 gave more than half of Mexican territory to the United States. Latino writers of that time could not avoid having some sort of involvement, either as activists or simply as observers of what was taking place.

What are some of the common themes you found in Latino writing as you assembled this collection?

First and foremost is the idea of the search for a place to call home, individually and collectively. Are we at home in America? What does America mean to us? And what do we mean to America? This question of home results in tension between rebellion and consent. A current throughout the collection is frustration, anger and outright rebellion, particularly during the Civil Rights era, and the quest for validation. Then there’s the gender theme: How is gender dealt with in Latino society? The works in the anthology also explore the impact of poverty and alienation on a person’s mind and spirit. And then there’s the theme of language: What are our words? Are they Spanish or English? Or are they to found in Spanglish?

A number of the Latino writers included in the anthology say Walt Whitman influenced them. Why do you think this is so?

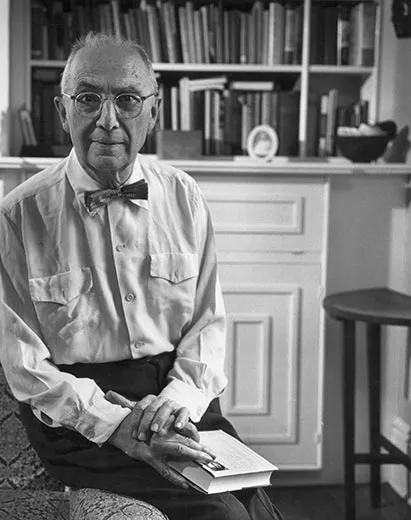

We can’t talk about America today without feeling that the ghost of Whitman is sitting next to us, particularly when you are dealing with so-called minority or ethnic literature. In the 19th century, Whitman was receptive to the idea of multitudes—a country that is made of many countries. He looks at New York City as a metaphor for the rest of the country, and that New York City is a symphony of voices, of backgrounds. In particular, when it comes to poetry, there are a lot of Latino writers that view him as a godfather, or even as a compadre. William Carlos Williams, Martín Espada, and Jimmy Santíago Baca, for instance. Whitman is in writers who want not only to produce aesthetic artifacts but also use those cultural and literary artifacts as tools or weapons for change.

In the section titled “Into the Mainstream” you say that Latinos are united by their language and minority status. Do you think that the literature will change when Latinos are longer in the minority?

It has been said that by the year 2050 one of every three Americans will be of Latino background. Maybe in 2050, you won’t have to put together a Norton Anthology of Latino Literature because Latino literature will be American literature. But, on the other hand, the more global the world and the country become, the more we emphasize our differences. The more we all look the same and eat the same food and dress the same way, the more we want to say that some of us came from Italy and some of us came from Ireland, or we’re Jewish or Latino. I think that we will see something not unlike the Jewish American experience, in which Latino culture becomes so integrated into the DNA of mainstream culture that it will be very difficult to distinguish between one and the other. How long that will take, I don’t know.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)