Christmas at the Smithsonian’s Dolls’ House Includes All the Trimmings—in Miniature

It’s ‘Deck the Halls’ with Christmas cheer at the beloved Victorian-style dollhouse at the National Museum of American History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/04/5c04c69f-e1eb-4a54-b6be-5ab4e6cdd55d/et2010-32411.jpg)

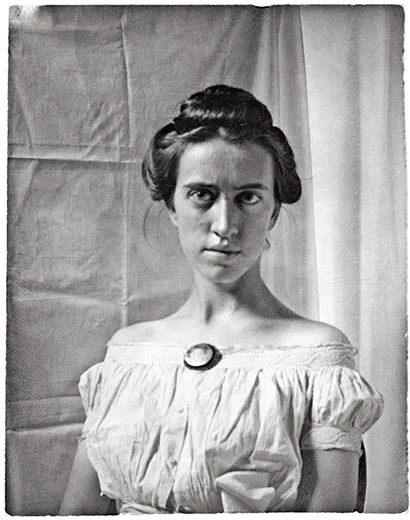

As the 1951 Christmas season approached, Faith Bradford, a retired librarian, came to the Smithsonian Institution to carry out what would become a holiday ritual. Bradford, a passionate dollhouse enthusiast who had amassed miniature furnishings and household items since childhood, had recently donated her collection—a 23-room dwelling furnished with 1,354 items of early 20th-century vintage—to the Institution.

The house's inhabitants included a father, called Peter Doll by Bradford; his wife, Rose Washington Doll; their ten children; the couple's in-laws; a household staff of five; and 20 pets, ranging from dogs to goldfish and including several presumably tame white rats.

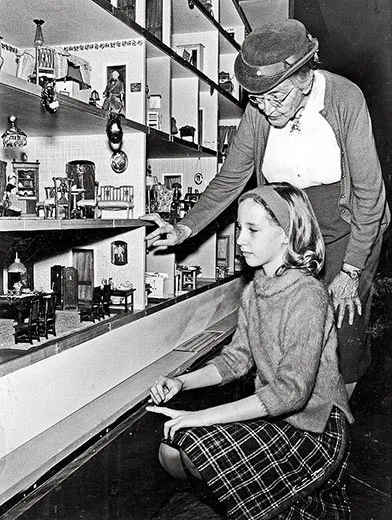

On that December day, Bradford had come to decorate the five-story house for the holidays. Down from the attic came tiny wreaths, as well as a fir tree fashioned of brush bristles and festooned with ornaments; elegantly wrapped miniature presents; and a scaled-down electric train set. Ever since, Bradford's house has been a crowd pleaser, particularly at holiday time.

Her great-nephew Phillips V. Bradford, who lives in Colorado, visits the installation, now at the National Museum of American History, whenever he is in Washington, though not without difficulty. "I can never get very close," he says. "There's always a crowd three or four deep."

Curator William L. Bird, author of America's Dollhouse, published by Princeton Architectural Press, describes the miniature mansion as "an iconic object, one of the Smithsonian's most popular attractions." Before she retired, Bird notes, Faith Bradford "was the first woman to head a division of the Library of Congress, the Card Catalogue Division."

In her meticulous scrapbook filled with neatly typed entries, she described Peter Doll as "about thirty-five years old. He is successful financially, with perhaps an inheritance as a solid background. He is a man of integrity, well regarded in his community, much loved by his family."

She further reported him to be "well-educated; witness his well-stocked library" and fond of sports—"by token of the trophy on his desk and his bicycle." His wife, Rose, "retains her charm at thirty-one. She has lost none of her social ease while acquiring the skills needed to direct her large household."

Even the goldfish had names—Goldie, Wiggle and Dart—though "no one knows which is which," says Bird. The children, we learn from Bradford's notes, include two sets of twins: Jimmy and Timmy are identical; Carol and Lucy are fraternal. The nanny, Bradford wrote, "is a Scot." The butler is named Gadsby. One of the dogs answers to Spot.

The attention to detail that Bradford lavished on the project is apparent in each room, where her eye for color, texture and minutiae is evident at every turn. The kitchen icebox holds tiny milk bottles; a miniature smoked ham hangs on the wall. The library contains titles including Washington's Farewell Address; a silver canister on a shelf represents a souvenir of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. But for all its wealth of objects, the house—as Bradford admitted in the early 1950s—remained a work in progress. "My passion for detail is such," she wrote, "that I shall never be completely satisfied with its creation."

Until her final days, Bradford, who died in 1970 at age 90, returned a couple of times each year to conduct what she described as "house cleanings" (by which she meant thorough dustings). Without fail, the winter tidyings-up coincided with holiday decorating. Nearly six decades after the house first went on view, it still does.

"At first," says Bird—recalling his reaction upon joining the museum in 1976—"I thought the tradition odd." But after a couple of years, he adds, the task "became something I looked forward to."

Bird acknowledges, however, that he isn't always punctual when it comes to removing the Christmas trimmings and returning them to the dollhouse attic. On one occasion, he recalls, "My boss, Margaret Brown Klapthor, asked me when the decorations were coming down. I replied that the Dolls left them up until the Super Bowl." To Bird's delight, he says, "She seemed perfectly content with my answer."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)