To Save and Project: Screening Restored Movies

A film festival at MoMA highlights those titles, either beloved and well-known or obscure yet fascinating, that may never reach the home market

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111014025015twilight_zone_thumb.jpg)

The 49th New York Film Festival draws to a close this weekend with a screening of Alexander Payne’s The Descendants. Critical response to the festival has been somewhat muted, perhaps because, as A.O. Scott pointed out in his New York Times summary, so many of the scheduled films will receive theatrical releases in the future.

One of the high points of the Festival was the appearance of the West Memphis Three for a screening of Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory (see my earlier posting). Interviewed on WNYC’s The Leonard Lopate Show, co-director Joe Berlinger described how moved he was to see the Three’s reactions as they watched a sunset from a Manhattan rooftop, free after 18 years in prison. (Disclaimer: my wife is the executive producer of the Leonard Lopate Show.) Paradise Lost 3 is a remarkable film, one that deserves to be seen by everyone who is interested in justice.

A festival coup was a sneak preview of director Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, adapted by John Logan from Brian Selznick’s children’s novel Hugo Cabret. Billed a “work in progress” at the screening, the completed Hugo will be released by Paramount on November 23. (Watch the trailer.) Disney employed a similar stunt during 1991′s Festival when it screened a rough draft of Beauty and the Beast. Scorsese also showed his documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World prior to its broadcast on HBO.

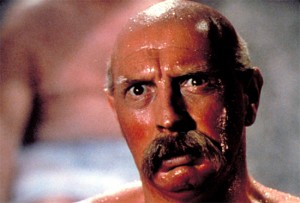

Roger Livesey in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). Image courtesy of Academy Film Archive, ITV Studios Global Entertainment, and the BFI.

Scorsese is making an appearance at a different New York festival that opens today at the Museum of Modern Art. To Save and Project: The Ninth MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation highlights 35 films from 14 countries, as well as a retrospective tribute to filmmaker Jack Smith. On November 7, Scorsese and his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker will be introducing the uncut, 163-minute version of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. It was directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the team behind such classics as I Know Where I’m Going and Black Narcissus. (Schoonmaker is Powell’s widow.)

Blimp is not too difficult to see, and in fact Criterion offers a well-regarded home video version. The same can’t be said for many of the other films in To Save and Project. Director Joe Dante opens the festival with The Movie Orgy (1968), a unique assemblage of trailers, commercials, training films, and newscasts that he and Jon Davidson screened at colleges 40 years ago. On Saturday, Dante will introduce his segment from Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), “It’s a Good Life,” along with Roger Corman’s The Intruder (1962), and an early anti-discrimination film starring William Shatner.

Due to rights complications, The Movie Orgy will most likely never be available to the home market. Many other restored films languish in a limbo of restricted access. It’s been over 20 years since I attended a screening of Under a Texas Moon (1930), the first sound Western shot in Technicolor and an early screen credit for Myrna Loy. Film buffs grumble about being unable to see the restored versions of The Big Parade (1925), King Vidor’s World War I epic, or Wings (1927), the only Best-Picture-winner not legally available on home video. Rights can be a huge stumbling block to museums and archives, making it difficult or impossible for fans to see their favorite movies.

And then some of the films in To Save and Project are just too obscure to warrant distributing to the home market. How about a series of five ethnographic shorts that noted documentarian Jean Rouch made in West Africa in the late 1940s? Or Robinzon Kruzo (1947), considered the first 3d feature-length film? To Save and Project devotes a segment to comedies from distributor Jean Desmet, to film and dance performances by Elaine Summers, and to five CinemaScope and widescreen films from Twentieth Century Fox.

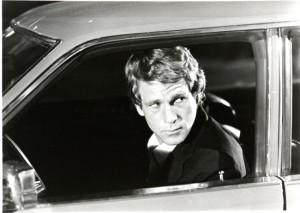

Some of these titles will eventually trickle out to Turner Classic Movies and the home market, like Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970), showcased in last year’s festival. But I am eagerly anticipating the chance to see hard-to-find titles like Afraid to Talk, a 1933 Universal melodrama about political corruption; Hoop-La (1933), a romantic comedy that was Clara Bow’s last screen role; and Les Halles centrales (1927), a documentary of a market in Paris by Boris Kaufman, later a noted cinematographer and the younger brother of Russian director Dziga Vertov. I also plan to attend The Driver (1978), Walter Hill’s existential film noir about getaway expert Ryan O’Neal, to see how it compares to Nicolas Winging Refn’s wildly overhyped new release Drive.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)