The National Museum of Health and Medicine

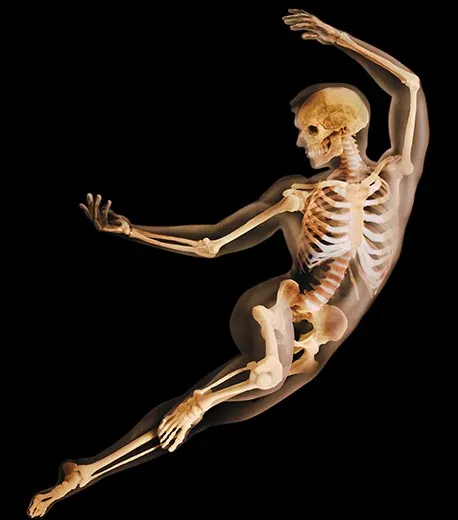

This Silver Spring, Maryland site scares and educates, with displays of prosthetic eyes, amputated limbs and incomplete skeletons

Victorian-era museums of medicine often seem like freak shows—corridors lined with displays of giant skeletons, deformed fetuses, amputated feet and cancerous lesions. But they were established with a noble purpose, as places where doctors-in-training could study actual specimens. The National Museum of Health and Medicine, in Washington D.C., which was created at the start of the Civil War to further the research of military field surgery and now is open to the public, is no exception. In 1862, Surgeon General William Hammond instructed Union doctors on the front lines to send him “specimens of morbid anatomy...together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed.” The Army Medical Museum (as the resulting collection became called) was staffed by doctors, and it quickly accumulated a wealth of grisly items for medical personnel to examine on their way to the front.

Today, staff members are no longer doctors and the exhibits relate to the history of military medicine, but there is still a vast archive of objects researchers can consult.

Prior to being in Silver Spring, the museum was housed within a wing of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, a facility that treats soldiers wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan. Near the entrance was a shattered human skull labeled “Effects of Canister Shot in the Civil War,” followed by more displays from that war: prosthetic eyes, a photograph of stacked amputated limbs. Close by were the leg bones of a certain Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, who donated his amputated limb to the museum and visited it regularly.

Perhaps the most famous items on display are from Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. They include fragments of the slain president’s skull, pieces of hair, part of the doctor’s blood-stained shirt cuff, and reproductions of Lincoln’s face and hands—even the lead ball removed from his head, labeled simply “The Bullet That Took the President’s Life.”

One past exhibit was almost as startling: “Trauma Bay II,” part of the actual field hospital used at the Army Air Force Base in Balad, Iraq, from 2004 to 2007. Although plaques explained that over 95 percent of soldiers treated there during that period survived, emergency military field surgery seemed hardly less bloodcurdling than it did in the Civil War. The museum continues to be a place for education, only these days the subject is the ghastly toll of war.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article stated that Lincoln's autopsy was performed at this location. Lincoln's autopsy took place at the White House. This version has been updated.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)