The Masked Merriment of Mardi Gras

For centuries, the day’s revelry has featured the liberated feeling of hiding in plain view

![]()

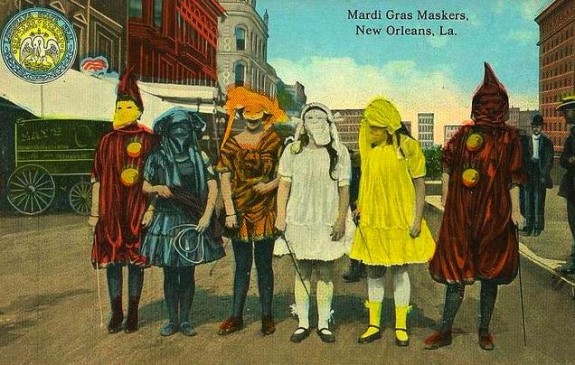

Shrove Tuesday is a day to be remembered by strangers in New Orleans, for that is the day for fun, frolic, and comic masquerading. All of the mischief of the city is alive and wide awake in active operation. Men and boys, women and girls, bond and free, white and black, yellow and brown, exert themselves to invent and appear in grotesque, quizzical, diabolic, horrible, strange masks, and disguises. Human bodies are seen with heads of beasts and birds, beasts and birds with human heads; demi-beasts, demi-fishes, snakes’ heads and bodies with arms of apes; man-bats from the moon; mermaids; satyrs, beggars, monks, and robbers parade and march on foot, on horseback, in wagons, carts, coaches, cars, &c., in rich confusion, up and down the streets, wildly shouting, singing, laughing, drumming, fiddling, fifeing, and all throwing flour broadcast as they wend their reckless way.

– James R. Creecy, Scenes in the South, and Other Miscellaneous Pieces, 1860

Costume Institute Fashion Plates, Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, Mardi Gras 1, Part 028, date unknown.

Drunken revelry. Beaded necklaces. Doubloon throws. Zulu coconuts. Today is Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday), the culmination of weeks of Carnival celebrations that end on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. It is a time when hundreds of thousands of tourists stream into New Orleans and treat the city like one huge frat party. Many local New Orleanians will avoid the French Quarter ,just as New Yorkers stay away from Times Square on New Year’s Eve. Yet, like New Year’s in New York City, Mardi Gras is an institution.

Mardi Gras made landfall in the United States back in the 17th century when the French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville set up camp 60 miles from New Orleans on the day that the holiday was being celebrated in France. He called the location Point du Mardi Gras. But, Mardi Gras and the accompanying masked balls associated with the holiday were outlawed when the Spanish governor took control of the area in 1766 as well as when it came under U.S. rule in 1803. But by 1823, the Creole population convinced the governor to permit masked balls. By 1827, wearing a mask in the street was legalized in New Orleans. (They’re now only legal to wear on Mardi Gras Day.) When the first official “krewe,” or elite social club, was established in 1857, the Mardi Gras parades that they organized became formalized annual occasions, which meant that parade participants donned masks and colorful regalia with greater frequency.

Taking cues from masquerade balls that made their way through Europe as early as the Middle Ages and Venetian carnival celebrations, the now-familiar face covers we see on Shove Tuesday (as Fat Tuesday is also known) mimic variations that have been around for centuries. The Bauta (full-faced mask shaped for ease of eating and drinking), Columbina (half mask), and Medico della Peste? (the beak-like steampunk-esque mask that is familiar to anyone who’s attended the interactive, immersive theatrical performance Sleep No More), but thankfully not the Moretta (a terrifying blank-faced mask held in place by biting a button inside the mask, thus inhibiting speech), all frequently associated with the Venice Carnival, are on grand display during the festivities (and legally to boot, as the law prohibiting mask-wearing, which is in effect throughout the year, is suspended on Mardi Gras Day in New Orleans). Today, the feathered, sequined, glittering disguises use the now-universal Mardi Gras colors originally established by the krewe of the Rex parade in 1872: purple symbolizing justice, green for faith and gold for power.

Scurlock Studio, Omega Mardi Gras, Washington, D.C., n.d. (c. 1940), National Museum of American History.

A mask is a funny thing. Slide one over your face and, with its exaggerated expression, the mask immediately transforms you into someone else (say, Richard Nixon) while also making you expressionless under a frozen guise. It’s also the manifestation of one’s id. According to Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, “in Robert Laffont’s A Dictionary of Symbols masks do not hide the persona, but reveal and liberate the lower tendencies of the true personality of the one who wears the mask.” Think Tom Cruise as doctor-by-day, sexual escapader-by-night in Eyes Wide Shut. Mardi Gras masks provide the freedom to hide behind, or embrace, the creature of our choosing, real or made-up—even, in James R Creecy’s words, “manbats from the moon.”

But not everyone celebrating Mardi Gras will follow the mask tradition. Tomorrow on Facebook you might see “Frat” Tuesday photos of girls exposing themselves wearing only beads and dudes drinking ’til they’ve vomited. Sadly, these revelers will wish they’d chosen to disguise themselves with “heads of beasts and birds” before taking those photos.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)