The Hamburger: A Quintessential American Meal

The hamburger is a part of our national identity. But how did the U.S. come to “own” the little beef cake sandwiches?

Anyone familiar with Popeye the Sailor—be it the comic strip or the animated cartoons—is also probably familiar with J. Wellington Wimpy, the cowardly mooch with a penchant for plotting schemes for how to get food without paying for it. Notably, Mr. Wimpy has an insatiable appetite for hamburgers, offering his famous catchphrase, “I will gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today” when he’s trying to score a patty. But he’s certainly not alone in his burger lust. With Memorial Day kicking off the summer vacation season, people all over the United States are firing up grills and getting their fill of the little beef cake sandwiches that have become a part of our national identity. But how did this country come to “own” the hamburger?

First off, let’s get a few things straight and define what a hamburger really is: a perfect marriage between a beef patty and a bun. Sliced bread is for sandwiches and patty melts. Bona-fide burgers require a carbohydrate complement specially engineered to absorb the meat juices of the patty and any toppings thereon. That said, as with many food origin stories, the hamburger’s beginnings are hazy; however, author Josh Ozersky did some serious detective work into tracing how this food came to be in his simply-title book The Hamburger: A History.

![]()

The hamburger had its forerunners—such as the Hamburg steak, a hodgepodge of mixed meats similar to our modern-day Salisbury Steak, that provided the poorest of the poor a cheap meal. Furthermore, it did not come from Hamburg, Germany; the earliest references to hamburger-like dishes come from English cookbooks. A number of people claimed to have had the brilliant idea of flattening a chunk of ground beef and slapping it on a bun. And trying to sort through all the “he says/she says” stories to figure out which one is correct is little more than an exercise in futility. Ozersky does, however, credit fry cook Walter Anderson and insurance salesman Billy Ingram for firmly planting hamburgers into the American consciousness.

Together, the pair founded White Castle, the first restaurant chain that mass-produced and sold burgers to the public. Ozersky credits Anderson, who started his first hamburger stand in 1916, with creating the modern-day hamburger and having the idea of replacing sandwich bread with specially-designed buns. But it was Ingram who knew how to market the product. A relentless promoter, he hawked hamburgers as a perfect foodstuff for tea parties, touted that they were good for one’s health and created a restaurant aesthetic—stately, white and regal—that subliminally told customers that burgers were safe and wholesome to consume. (In the wake of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which exposed the unsanitary conditions of the meat packing industry, Americans were taking a harder look at their food before they ate it.) Together, the White Castle team elevated burgers from working class junk food to a food for everybody. Other hamburger chains began to spring up and by the 1940s it was a quintessential American meal.

And hamburgers have proven to be a versatile medium—some blogs are entirely devoted to the art and architecture of crafting a burger. The Hamblogger combines burger lust with photojournalism to capture the entire hamburger dining experience, documenting the eateries and their own special spins on the all-beef patty on a bun.

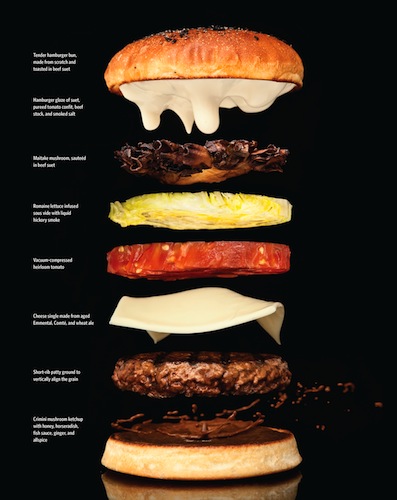

And then there’s the Modernist Cuisine, that lavishly and innovatively illustrated compendium on cooking wherein the authors take a hardcore look at how hamburgers are—and ought to be—prepared. For starters, they dispel the myth that searing meat locks in juices and gives you that desirable crust: all the liquid you want to hold in is escaping into the pan and creating those tantalizing sizzling noises. Their solution is to cook the patty sous vide to cook the meat, and then freeze the burger with liquid nitrogen before deep frying it in oil in order to create a crust. (They say the freeze/fry method prevents the patty from breaking apart during cooking.) Some have tried preparing the high-maintenence burger—it takes roughly 30 hours from start to finish, including making the buns and sauces. And of course the finished product doesn’t look nearly as photogenic as the illustration in the book.

But for most of us, I’m sure a grill will work just fine. And for those who don’t feel like toiling in the kitchen, you can download a Burger GPS app to find a fun hamburger spot nearby.