Recording the Ju/’hoansi for Posterity

For 50 years, John Marshall documented one of Africa’s last remaining hunter- gatherer tribes in more than 700 hours of film footage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Priceless-John-Marshall-631.jpg)

The African giraffe stumbles to a halt, bewildered by the poisoned spears studding its breast and flanks. Moments later, it falls stiffly backward. The giraffe's slender legs point skyward, then swing sideways as it collapses in the desert dust.

The scene flashes to a Ju/'hoansi hunter, tearing into a joint of glistening red meat with his knife.

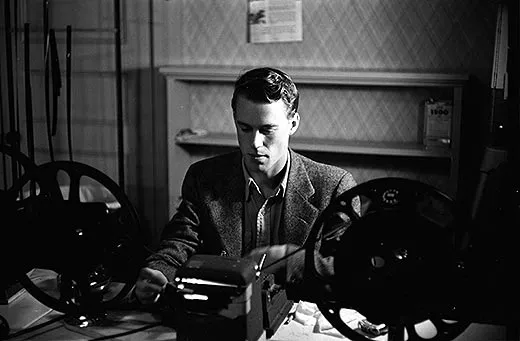

"Sorry, I should have warned you about that part—a little sad, isn't it?" says film archivist Karma Foley, 34, as she presses a button to pause the flickering images on the video monitor at the Smithsonian's Human Studies Film Archives (HSFA). Established in 1981, the archives are dedicated to collecting and preserving anthropological films—including John Marshall's footage of the Ju/'hoansi (zhun-twa-see) people, whom he considered a second family.

Marshall, who died at age 72 in 2005, meticulously documented, on film and video, the lives of the hunter-gatherers in northeast Namibia between 1950 and 2000. He donated more than 700 hours of his footage to the HSFA. Recently, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) added the Marshall archive to its Memory of the World Register—joining Anne Frank's diary, the Magna Carta and other watershed items. The Marshall archive, according to Unesco, is "one of the seminal visual anthropology projects of the 20th century."

Foley knew Marshall at the end of his career and helped him edit and produce a six-hour retrospective series, A Kalahari Family, released in 2002. "He could be difficult to work with because he demanded perfection, but it was easy to deal with that because you knew his heart was in the right place," she says.

Marshall was born into a wealthy New England family. His father, Laurence, was the founding president of the radar defense company Raytheon, and when he retired, he wanted to do something useful. So when anthropologists at Harvard's Peabody Museum told him that no one knew if the tribal people of Africa's Kalahari Desert still engaged in hunter-gatherering, he decided to find out.

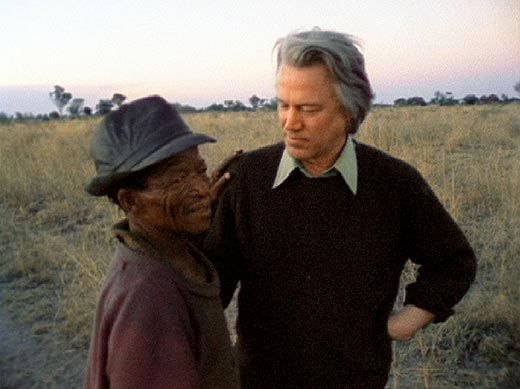

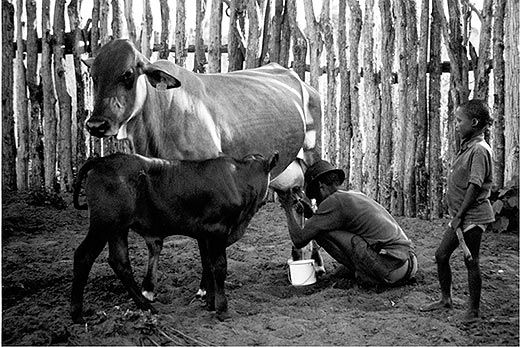

In 1950, Laurence and his 18-year-old son, John, made their first trip to the South African territory that is now Namibia. After questioning local people through interpreters, they deduced a likely spot to find the Ju/'hoansi—a tribe of about 1,200 people who roamed freely over hundreds of miles within a northern region of the Kalahari called Nyae Nyae. The Ju/'hoansi plucked anything edible from the earth, sucked water from roots and occasionally feasted on wild animals. It was not an easy life. "We were owners of thirst and owners of hunger," Toma Tsamkxao, a Ju/'hoansi man who befriended John, says in one of the films.

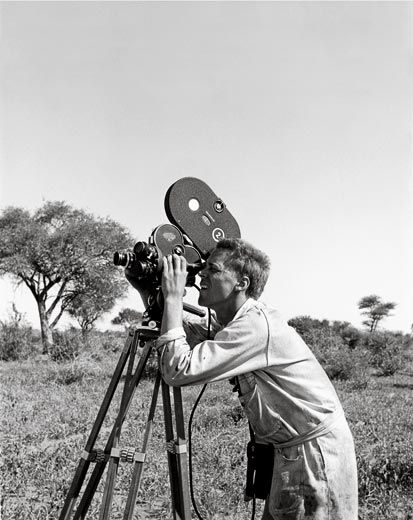

The Marshalls, along with John's mother, Lorna, and sister, Elizabeth, returned the following year to conduct a full ethnographic study. John, who had no filmmaking experience, learned quickly. His father "handed John a 16-mm film camera and said, ‘You need to record everything we see, otherwise no one will believe us,'" says Foley.

John Marshall returned to Nyae Nyae many times over the next decade, camera always in hand. In 1958, as his films began to gain international attention, Marshall was banned from the region by the South African government, which likely saw his support for indigenous peoples as a challenge to its apartheid regime, Foley says. By the time Marshall was able to return, 20 years later, Tsamkxao and the rest of his people were living on a reservation. Their traditional way of life, which had lasted for millennia, was over.

"Looking back, I'm struck by how naive we all were about the future," Marshall says in A Kalahari Family. "Neither Toma's family nor my family was prepared for the speed and magnitude of the change to come."

Designating Marshall's work as part of the Memory of the World project is fitting, Foley says. "At one time all people lived by hunting and gathering. It's a shared human experience going all the way back."