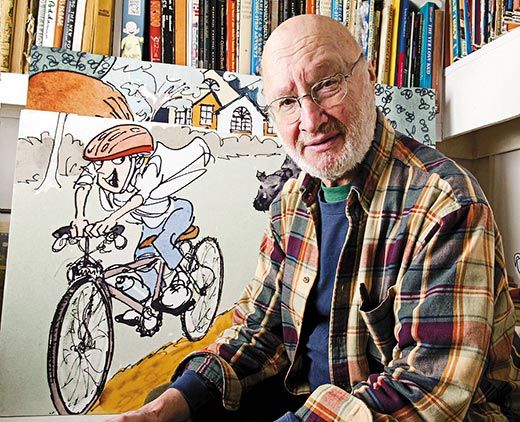

Q and A: Jules Feiffer

The cartoonist, illustrator, author and playwright reflects on happy memories and the positive side of failure

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/QA-Jules-Feiffer-631.jpg)

Jules Feiffer has prodded and entertained Americans with his sharp wit for over 50 years by way of cartoons, illustrations, plays and books—including his 2010 memoir, Backing Into Forward. Recently, he spoke at the Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture about photographer Bob Landry’s blithesome portrait of dancer Fred Astaire. Feiffer was interviewed by the magazine’s Jesse Rhodes.

In your memoir you refer to Astaire as your guru. How did that love and reverence for him come about?

I was a child of the Great Depression and the only cheer that came through for many of us in those times was in the form of popular entertainment People were living from hand to mouth and in near poverty situations and while we weren’t suffering or starving or anything like that, it was not a happy time. And the happy times were up on the screen or the happy times were on the radio or the happy times were, in my case, the comic strips and later in comic books. One of the most happy times was those occasions was when my parents would take the three of us to the local movie theater to see Fred and Ginger. That was a memorable occasion because the ease and effortlessness—or apparent effortlessness—of Astaire’s dancing communicated a form of high spirits and optimism and cheer that communicated itself as hope—at least to a substantial part of the population, or at least to me.

Would you say that Fred Astaire is a personal hero of yours?

There were many personal heroes, most of them cartoonists.

Which cartoonists?

As a kid it was EC Segar who wrote and drew Popeye. Milton Caniff who wrote and drew Terry and the Pirates. Al Capp who did Lil Abner and later on Walt Kelly who did Pogo, Crockett Johnson who did Barnaby. These were brilliant, brilliant men who were doing some remarkable work at that time.

What is heroic about Fred Astaire?

I think heroic is the wrong word. Inspiring is a much better word. He was inspirational. Thank god he wasn’t heroic because heroic people usually end up getting into trouble—they send you into war and things like that. There were months and months of hard work that went into making a movie with only one purpose in mind and that was to do something difficult and make it look easy.

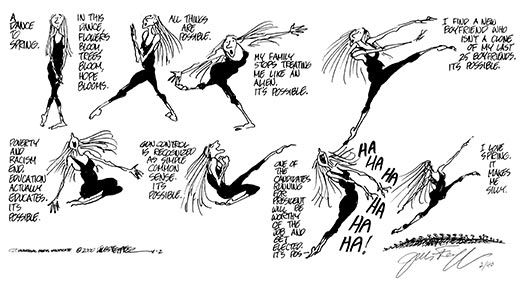

The dancer as a figure is an image that pops up in your work time and again. Why does that image appeal to you?

It’s hard to explain. It’s a complicated question and I’m not sure how to answer it simply, but from the time I began my Village Voice cartoon in the 50s, modern dance was taking off and I visited periodically that world and took in dance and had friends who were dancers. I saw the dancer as an ideal subject matter for the kind of comments I wanted to make and embodied in her all the ambivalent ambiguity, doubt, self-doubt, self-reproach and all those other feelings—neurotic and not neurotic, political and non-political. And also because she moved all the time she was leaping and arabesque-ing and doing this and doing that and as opposed to most of my figures who just stood and talked. So it was a lot more fun drawing her than it was my other characters.

Do you see the art of dance and the art of illustration as being related?

I never thought of it. I think everything is interrelated but I never gave it that much thought.

Has your journey through life been anything like Milo’s in The Phantom Tollbooth?

All I did was illustrate the book. I had nothing to do with the writing of it.

50 years after doing The Phantom Tollbooth, Norton Juster and I have collaborated for only the second time in our careers and that picture book published by Scholastic and coming out in the fall.

You’ve been a media presence for over 50 years. Has your opinion of your work ever changed?

First of all, the work has always been fun. I’ve always enjoyed doing it. The only time I haven’t loved it was when it stopped being a challenge and then the quality would decline. But when I can figure out ways of challenging myself the fun came back and the work improved and what’s impressed me most about myself is how much better I learned to draw over 50 years.

In your memoir you open with a line: “Success is nothing to sneeze at, but failure, too, offers great possibilities.” The idea of failure is another theme in your work. What is the value of failed experiences?

Particularly as an American, when we are taught—as other cultures do not teach—that failure is a bad thing. It’s looked down upon. Don’t be a loser. We have all sorts of negative notions about failure and so the hidden message is don’t risk anything. Don’t take chances. Be a good boy. Stay within the limits. Stay within the proper boundaries and that way you won’t get into trouble and you won’t fail. But of course in the arts and virtually anything else that leads a satisfactory life, failure is implicit. You try things, you fall on your face, you figure out what went wrong, you go back and try them. And what I was hoping to do for the readers of my book—particularly young readers—was tell them that a lot of the good advice they got should simply be ignored.

You’ve done comic strips, children’s books, plays and movies. What is your next creative project?

Other than having a few children’s books to illustrate and one that I’ve just written and will also illustrate, I’m working on a book about humor during the Great Depression and how humor got us through those times in a way that is absent in these times.