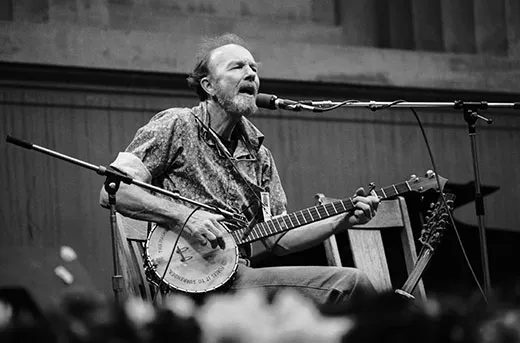

From the Archives: Pete Seeger on What Makes a Great Protest Song

To mark the centennial birthday of the late folk icon, Smithsonian Folkways has released a six-CD collection featuring 20 previously unreleased tracks

Editor's Note, May 3, 2019: In honor of Pete Seeger's 100th anniversary Smithsonian Folkways has released the definitive, career-spanning six-CD anthology, titled Pete Seeger, which celebrates the singer/songwriter with 20 previously unreleased tracks and live performances. A 200-page compendium of Seeger's essays and commentary, organized by Smithsonian archivist and curator Jeff Place, includes historic photographs and liner notes. To honor the occasion, we went back into our archives to highlight reporter Aviva Shen's 2012 interview with the then-92-year-old folksinger on one of his first concerts at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine:

In March of 1960, at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, a campus radio station recorded a Pete Seeger concert. The eight reel-to-reel tapes made that night have now been recast into a 2-CD set, due out April 17 from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. In The Complete Bowdoin College Concert 1960, the first-ever complete release of one of his community concerts, Seeger performs early versions of songs that would, in just a few years, captivate the entire nation, including anti-war ballad “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” Pete Seeger reflects on his legacy in a discussion with the magazine’s Aviva Shen.

Tell me about how you got started doing college concerts?

I think it was 1953. I was singing for $25 a day for a small private school in New York City. And I was keeping body and soul together with $25 a week; maybe I’d make another $25 on the weekend. But then some students from Oberlin asked me to come out. They said, we’ve got the basement of the art department and we think if we pass the hat, we’ll make $200, so you’ll be able to pay for the bus trip out. So I took a bus out to Cleveland and they picked me up, and sure enough we made more than that passing the hat. The next year I sang in the chapel for 500 people and I got $500. And the year after that, I sang in the auditorium, which had 1000 people and I got paid $1000. So that was when I started going from college to college to college.

Actually, this is probably the most important job I ever did in my life. I introduced the college concert field. Before that only John Jacob Niles had tried to sing college concerts and he’d dress up in a tuxedo, and things were very formal. I made things as informal as I could and went from one college to another and made a good living out of it.

How did the students respond?

Oh, they’d sing along with me.

Do you have any favorite memories of the tours?

I remember introducing a young black man, who’d made up a good song in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. He was only 16 years old, but he got an ovation from the crowd. He was working for Dr. King, organizing things in Chicago. Then in Wisconsin, I’ll never forget. We were in a big arena, which holds 5,000 or 6,000 people, and they handed me a letter from one of the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and said, “Would you please read this letter? He can’t come, but he wrote us a letter and we think that you could read it.” I read this with all the drama I could. Then I said “SIGNED” and just after I said it, there was a huge clap of thunder overhead. There was a rainstorm, and everybody started laughing. Because it was as though God was signing the letter.

When did you start using music as a cause?

My father was in the Communist party way back in the late 1920s, early 30s. He thought music should be part of the struggle. Although he was a classical musician and wrote a column for the Daily Worker on the world of music, he also started with the help of a few friends a group called the Composer’s Collective. They said, “If there’s going to be a new society, there must be a new music.” At any rate, the proletariat was not interested in what they were producing. But before they disbanded, he thought they might put out a fun little booklet called “Rounds About the Very Rich.” We all know rounds like Three Blind Mice and Frère Jacques but he wrote a round: “Joy upon this earth, to live and see the day/When Rockefeller Senior shall up to me and say/Comrade can you spare a dime?” I know these well because I went on a trip to the Adirondacks with my brother and a friend of his and we sang these rounds of his together as we tromped through the Adirondacks. So I was very well aware that music could be part of the whole big struggle.

Do you think there is a lot of protest music happening now?

It’s all over the place. One magazine, Sing Out, is full of protest songs. It started 30, 40 years ago. It nearly went bankrupt in New York, but one of the volunteers took out of the New York office a truckload of paper, and he started Sing Out all over again. It’s never been a big seller, but it prints. My guess is that they’re all around the world, protest songs. Of course, I usually tell people if the human race is still here in a hundred years, one of the main things that will save us is the arts. I include the visual arts, the dancing arts as well as the musical arts, you might even include the cooking arts and the sports arts—Nelson Mandela got Africa together with rugby. And China used ping-pong.

So what do you think music has had the most impact on?

Plato supposedly said that it’s very dangerous to have the wrong kinds of music in the republic. There’s an Arab proverb that says “when the king puts the poet on his payroll, he cuts off the tongue of the poet.” I think they’re both right. Of course Plato was an extremely conservative man. He thought that democracy was next to mob rule. He didn’t approve of democracy.

Do you have a favorite song that you’ve performed or written?

I keep reminding people that an editorial in rhyme is not a song. A good song makes you laugh, it makes you cry, it makes you think. Now, Woody Guthrie will have his 100th birthday this July 14. He wrote thousands of songs. Every day of his life he was jotting down verses on a little pad in his pocket and once his pad was full he’d get a new one. We were riding in a plane once to sing for some strikers in a union in Pittsburgh, and I was reading a newspaper or magazine. Lee Hays, the bass singer, fell asleep, but Woody was jotting down something on a piece of paper they had given him and he left the piece of paper in his seat when he got up to go. I went over to get it. He had verses about, what are these people below us thinking as they see this metal bird flying over their head, and what’s the pretty stewardess going to do tonight, where is she going to be. I said “Woody, you should know how I envy you being able to write songs like this.” He literally wrote verses every day of his life. And if he couldn’t think of a verse, he’d go on and write a new song. Quite often though, when he got his verse written, he’d think of some old melody that people knew which fit his verses.

Haven’t you done that?

There was an Irish lumberjack song, and I didn’t know I was using it or misusing it. But I was writing in an airplane, and the verse of this Irish lumberjack song, “Johnson says he’ll load more hay, says he’ll load ten times a day.” I was making up a verse: “Where have all the flowers gone, long time passing.” Well, it probably will reach more people than any other song I’ve written. Marlene Dietrich sang it around the world. When her youthful glamour was gone, she had Burt Bacharach put together a small orchestra and for several years she sang around the world. If she was in an English-speaking country like Australia she’d sing it in English, but if she was in Buenos Aires or Tokyo, she’d sing the German verse. The German translation sings better than the English: “Sag mir, wo die Blumen sind.” When she went back to Germany, the old Nazis were out to run her down, “don’t listen to this woman, she sang for the soldiers fighting us!” But that very month her song was number one on the German Hit Parade.

How do you feel about your songs getting covered and interpreted by so many other people?

I’m very proud. It’s a great honor to have different people sing it—even if they sing them differently. Ani Difranco got a group of young men, I think all 10, 11, 12 years old called Roots of Music, and they have a brass band, trumpets and clarinets and so on down in New Orleans. They used a song, which I recorded; I didn’t write the song but I recorded it with my banjo and it became well known: “Which Side Are You On.” By the time they got done rearranging it, you wouldn’t think it had anything to do with my song, except the title.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)