A Lost Work by Langston Hughes Examines the Harsh Life on the Chain Gang

In 1933, the Harlem Renaissance star wrote a powerful essay about race. It has never been published in English—until now

:focal(323x236:324x237)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/a8/71a8b7f6-40a7-48fc-ad74-025fc06eebf6/hughes-opener-letterboxed.jpg)

It’s not every day that you come across an extraordinary unknown work by one of the nation’s greatest writers. But buried in an unrelated archive I recently discovered a searing essay condemning racism in America by Langston Hughes—the moving account, published in its original form here for the first time, of an escaped prisoner he met while traveling with Zora Neale Hurston.

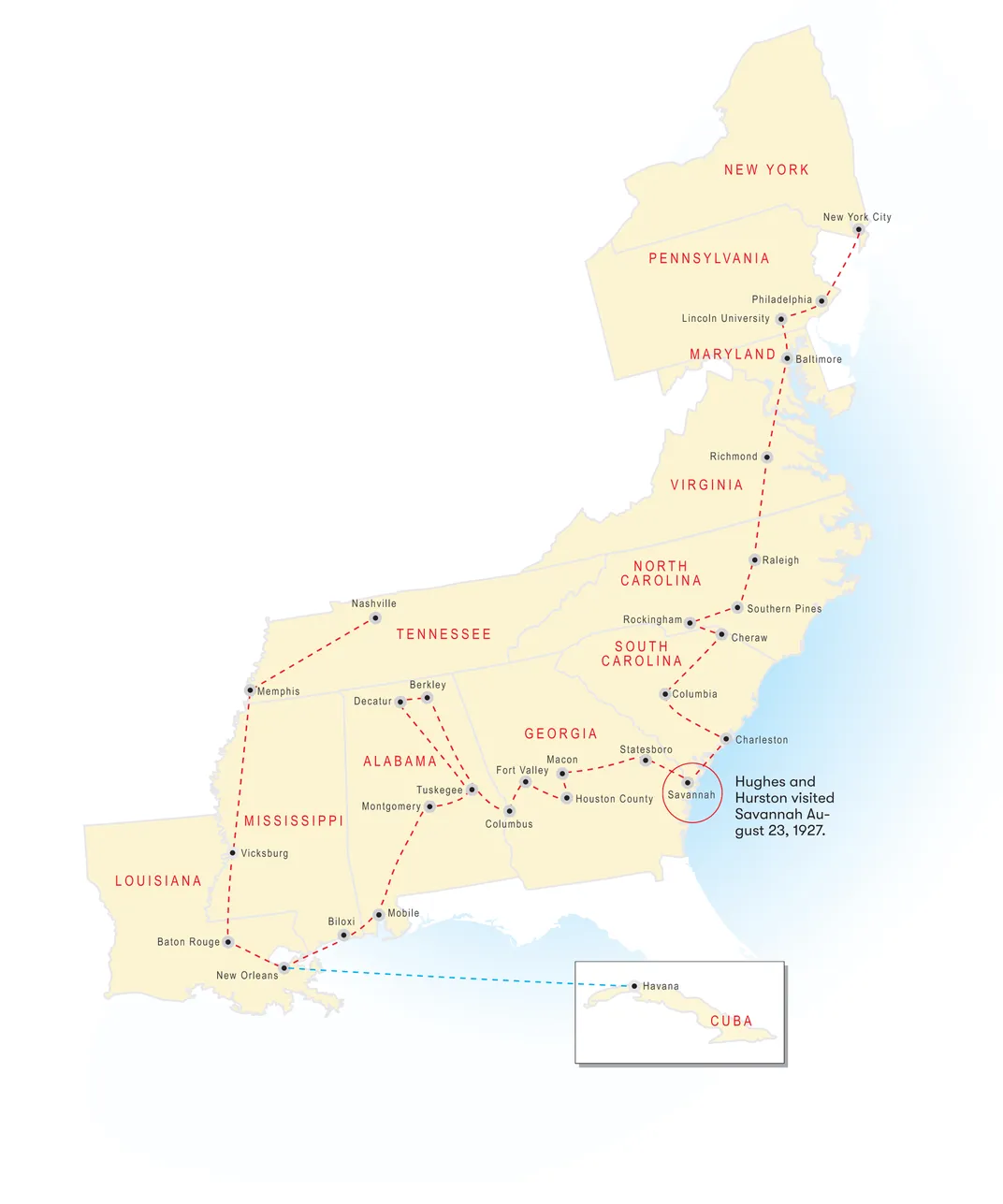

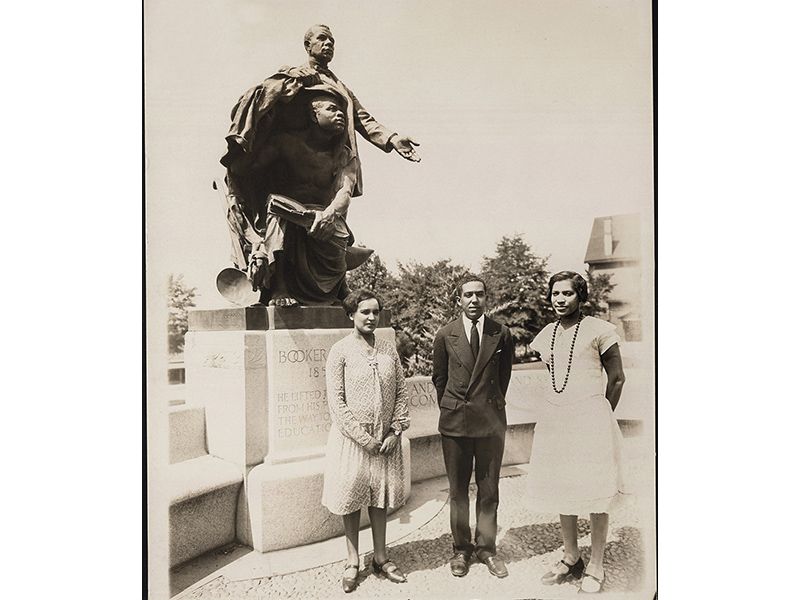

In the summer of 1927, Hughes lit out for the American South to learn more about the region that loomed large in his literary imagination. After giving a poetry reading at Fisk University in Nashville, Hughes journeyed by train through Louisiana and Mississippi before disembarking in Mobile, Alabama. There, to his surprise, he ran into Hurston, his friend and fellow author. Described by Yuval Taylor in his new book Zora and Langston as “one of the more fortuitous meetings in American literary history,” the encounter brought together two leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance. On the spot, the pair decided to drive back to New York City together in Hurston’s small Nash coupe.

The terrain along the back roads of the rural South was new to Hughes, who grew up in the Midwest; by contrast, Hurston’s Southern roots and training as a folklorist made her a knowledgeable guide. In his journal Hughes described the black people they met in their travels: educators, sharecropping families, blues singers and conjurers. Hughes also mentioned the chain gang prisoners forced to build the roads they traveled on.

A Literary Road Trip

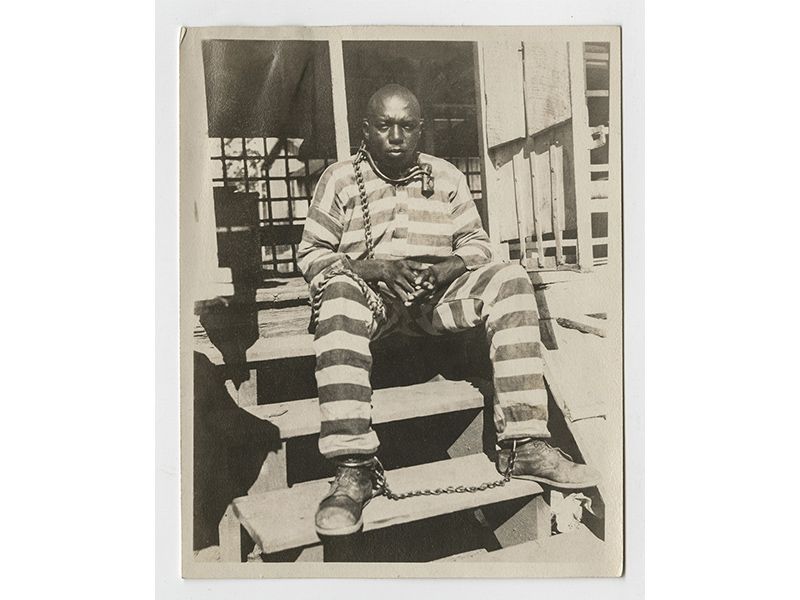

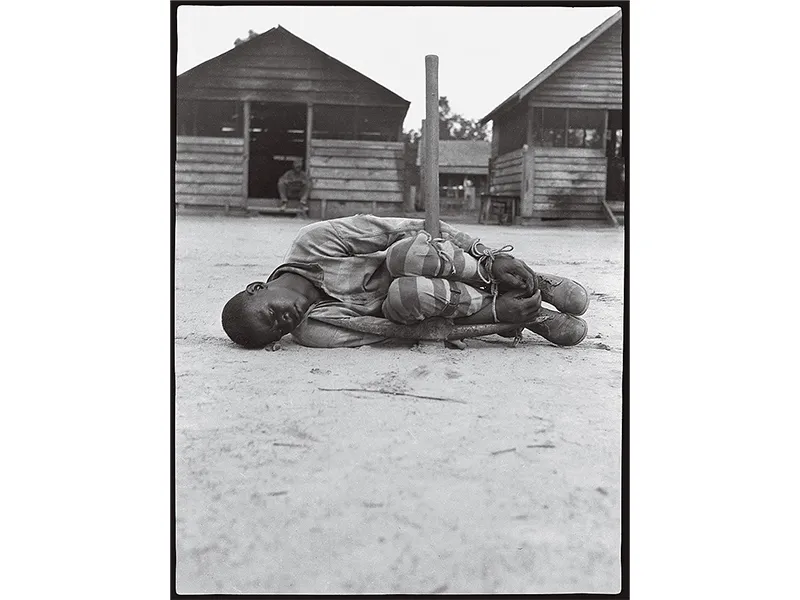

Three years later, Hughes gave the poor, young and mostly black men of the chain gangs a voice in his satirical poem “Road Workers”—but we now know that the images of these men in gray-and-black-striped uniforms continued to linger in the mind of the writer. In this newly discovered manuscript, Hughes revisited the route he traveled with Hurston, telling the story of their encounter with one young man picked up for fighting and sentenced to hard labor on the chain gang.

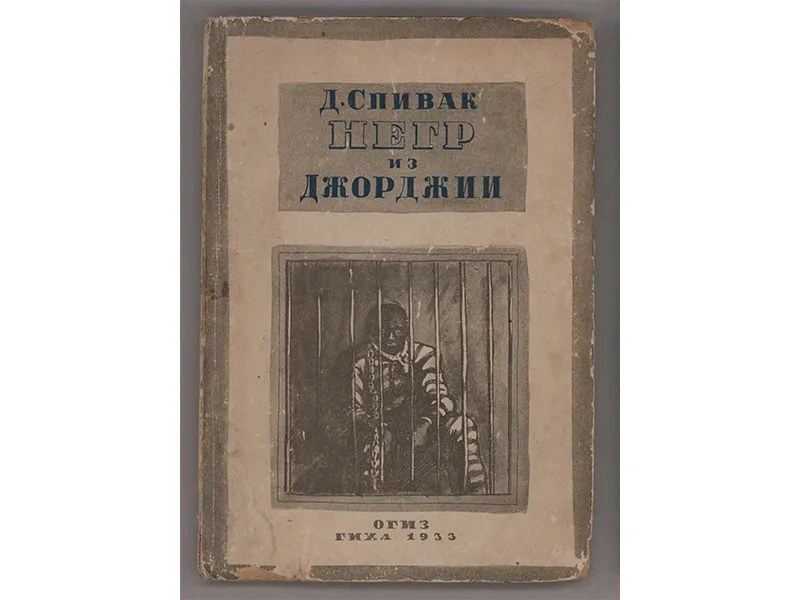

I first stumbled upon this Hughes essay in the papers of John L. Spivak, a white investigative journalist in the 1920s and 1930s, at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Not even Hughes’ authoritative biographer Arnold Rampersad could identify the manuscript. Eventually, I learned that Hughes had written it as an introduction to a novel Spivak published in 1932, Georgia Nigger. The book was a blistering exposé of the atrocious conditions that African-Americans suffered on chain gangs, and Spivak gave it a deliberately provocative title to reflect the brutality he saw. Scholars today consider the forced labor system a form of slavery by another name. On the final page of the manuscript (not reproduced here), Hughes wrote that by “blazing the way to truth,” Spivak had written a volume “of great importance to the Negro peoples.”

Hughes titled these three typewritten pages “Foreword From Life.” And in them he also laid bare his fears of driving through Jim Crow America. “We knew that it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South,” he wrote. (Hurston packed a chrome-plated pistol for protection during their road trip.)

But a question remained: Why wasn’t Hughes’ essay included in any copy of Spivak’s book I had ever seen? Buried in Spivak’s papers, I found the answer. Hughes’ essay was written a year after the book was published, commissioned to serve as the foreword of the 1933 Soviet edition and published only in Russian.

In early 1933, Hughes was living in Moscow, where he was heralded as a “revolutionary writer.” He had originally traveled there a year earlier along with 21 other influential African-Americans to participate in a film about American racism. The film had been a bust (no one could agree on the script), but escaping white supremacy in the United States—at least temporarily—was immensely appealing. The Soviet Union, at that time, promoted an ideal of racial equality that Hughes longed for. He also found that he could earn a living entirely from his writing.

For this Russian audience, Hughes reflected on a topic as relevant today as it was in 1933: the injustice of black incarceration. And he captured the story of a man that—like the stories of so many other young black men—would otherwise be lost. We may even know his name: Hughes’ journal mentions one Ed Pinkney, a young escapee whom Hughes and Hurston met near Savannah. We don’t know what happened to him after their interaction. But by telling his story, Hughes forces us to wonder.

Foreword From Life

By Langston Hughes

I had once a short but memorable experience with a fugitive from a chain gang in this very same Georgia of which [John L.] Spivak writes. I had been lecturing on my poetry at some of the Negro universities of the South and, with a friend, I was driving North again in a small automobile. All day since sunrise we had been bumping over the hard red clay roads characteristic of the backward sections of the South. We had passed two chain gangs that day This sight was common. By 1930 in Georgia alone, more than 8,000 prisoners, mostly black men, toiled on chain gangs in 116 counties. The punishment was used in Georgia from the 1860s through the 1940s., one in the morning grading a country road, and the other about noon, a group of Negroes in gray and black stripped [sic] suits, bending and rising under the hot sun, digging a drainage ditch at the side of the highway.Adopting the voice of a chain gang laborer in the poem “Road Workers,” published in the New York Herald Tribune in 1930, Hughes wrote, “Sure, / A road helps all of us! / White folks ride — /And I get to see ’em ride.” We wanted to stop and talk to the men, but we were afraid. The white guards on horseback glared at us as we slowed down our machine, so we went on. On our automobile there was a New York license, and we knew it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South. Even peaceable Negro salesmen had been beaten and mobbed by whites who objected to seeing a neatly dressed colored person speaking decent English and driving his own automobile.The NAACP collected reports of violence against blacks in this era, including a similar incident in Mississippi in 1925. Dr. Charles Smith and Myrtle Wilson were dragged from a car, beaten and shot. The only cause recorded: “jealousy among local whites of the doctor’s new car and new home.” So we did not stop to talk to the chain gangs as we went by.

But that night a strange thing happened. After sundown, in the evening dusk, as we were nearing the city of Savannah, we noticed a dark figure waving at us frantically from the swamps at the side of the road. We saw that it was a black boy.

“Can I go with you to town?” the boy stuttered. His words were hurried, as though he were frightened, and his eyes glanced nervously up and down the road.

“Get in,” I said. He sat between us on the single seat.

“Do you live in Savannah?” we asked.

“No, sir,” the boy said. “I live in Atlanta.” We noticed that he put his head down nervously when other automobiles passed ours, and seemed afraid.

“And where have you been?” we asked apprehensively.

“On the chain gang,” he said simply.

We were startled. “They let you go today?”In his journal, Hughes wrote about meeting an escaped convict named Ed Pinkney near Savannah. Hughes noted that Pinkney was 15 years old when he was sentenced to the chain gang for striking his wife.

“No, sir. I ran away.In his journal, Hughes wrote about meeting an escaped convict named Ed Pinkney near Savannah. Hughes noted that Pinkney was 15 years old when he was sentenced to the chain gang for striking his wife. That’s why I was afraid to walk in the town. I saw you-all was colored and I waved to you. I thought maybe you would help me.”

Gradually, before the lights of Savannah came in sight, in answer to our many questions, he told us his story. Picked up for fighting, prison, the chain gang. But not a bad chain gang, he said. They didn’t beat you much in this one.Guard-on-convict violence was pervasive on Jim Crow-era chain gangs. Inmates begged for transfers to less violent camps but requests were rarely granted. “I remembered the many, many such letters of abuse and torture from ‘those who owed Georgia a debt,’” Spivak wrote. Only once the guard had knocked two teeth out. That was all. But he couldn’t stand it any longer. He wanted to see his wife in Atlanta. He had been married only two weeks when they sent him away, and she needed him. He needed her. So he had made it to the swamp. A colored preacher gave him clothes. Now, for two days, he hadn’t eaten, only running. He had to get to Atlanta.

“But aren’t you afraid,” [w]e asked, “they might arrest you in Atlanta, and send you back to the same gang for running away? Atlanta is still in the state of Georgia. Come up North with us,” we pleaded, “to New York where there are no chain gangs, and Negroes are not treated so badly. Then you’ll be safe.”

He thought a while. When we assured him that he could travel with us, that we would hide him in the back of the car where the baggage was, and that he could work in the North and send for his wife, he agreed slowly to come.

“But ain’t it cold up there?” he said.

“Yes,” we answered.

In Savannah, we found a place for him to sleep and gave him half a dollar for food. “We will come for you at dawn,” we said. But when, in the morning we passed the house where he had stayed, we were told that he had already gone before daybreak. We did not see him again. Perhaps the desire to go home had been greater than the wish to go North to freedom. Or perhaps he had been afraid to travel with us by daylight. Or suspicious of our offer. Or maybe [...]In the English manuscript, the end of Hughes’ story about the convict trails off with an incomplete thought—“Or maybe”—but the Russian translation continues: “Or maybe he got scared of the cold? But most importantly, his wife was nearby!”

Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates. Copyright 1933 by the Langston Hughes Estate