Holiday Delivery From the Graf Zeppelin

In 1934, a zeppelin originating in Germany and bound for Brazil carried a cargo of Christmas cheer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/graf-zeppelin-Christmas-letter-631.jpg)

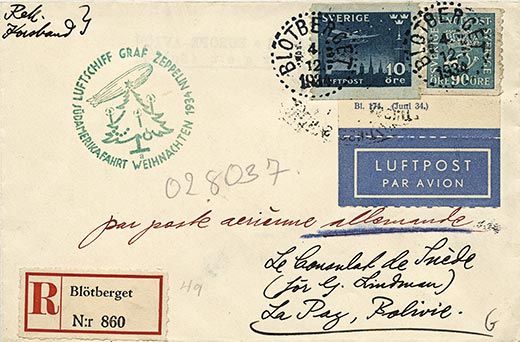

On December 8, 1934, the dirigible Graf Zeppelin—named for one inventor of hydrogen airships, Graf (Count) Ferdinand von Zeppelin—departed its Friedrichshafen, Germany, home base on its 418th flight, bound for Recife, Brazil. At the height of the Christmas season, the 776-foot-long dirigible carried 19 passengers, holiday mail and a load of freshly cut Christmas trees.

The cards and letters it transported bore a distinctive mark on their envelopes: a small image (known to collectors as a cachet) stamped in ink, depicting the zeppelin and a fir tree festooned with candles in Nordic fashion. One of those envelopes, now darkened with age, also bears traces of a second mark, applied during a train trip across Germany. In the 1950s, John P.V. Heinmuller, a Longines Watch Company executive and an aviation enthusiast, donated 2,000 envelopes once transported by zeppelin to the Smithsonian; today, the collection resides in the National Postal Museum (NPM).

Recipients of the Graf Zeppelin's seasonal delivery would be some of South America's many German immigrants, drawn to the resource-rich continent by the promise of wealth. "There was a huge German population in South America in the '30s," says Cheryl Ganz, a curator at the NPM. "Surrounded by palm trees, they obviously had a longing for traditional fir trees. Since the Graf Zeppelin could make the trip nonstop in less than four days, much faster than any ship, the trees would still be fresh when they arrived." The craft landed in Recife on December 12 and went on to Rio de Janeiro, where it arrived on December 13, bringing the last of its Christmas tree shipment to holiday revelers.

In those days, only giant airships could carry enough fuel to make nonstop trans-Atlantic flights. As early as 1921, Hugo Eckener, a former journalist who succeeded Zeppelin as head of the dirigible company, had investigated possible routes from Spain to South America by making a voyage on a cargo ship. During the crossing, Eckener observed the kinds of weather patterns and storms an airship might encounter. He calculated potential dirigible routes based on prevailing sea lanes. After the voyage, Eckener described himself as "very well satisfied" that the "area [was] suitable for flying."

The Graf Zeppelin made its first trans-Atlantic demonstration flight in October 1928 and was making regularly scheduled deliveries by the summer of 1934. Mail carried by zeppelin bore the distinctive cachets and postmarks. "The airships were the pathfinders for later fixed-wing flights," says Ganz. "Because the passenger and crew cabin wasn't pressurized, [dirigibles] had to fly low—low enough to see the faces of people on ships they passed over—so the crew had to figure out wind currents and weather patterns."

The age of dirigibles was relatively brief. It began in 1874, when Count von Zeppelin, a former cavalry general, began working on plans for lighter-than-air, propeller-driven balloons. Dirigibles began flying before World War I. During that conflict, they were used as scout aircraft and for bombing raids.

After the war, the count's company fell on hard times and was rescued by Eckener. In 1919, a British military crew made the first nonstop, trans-Atlantic flight, in a British-built dirigible, getting an eight-year jump on Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis. But the real liftoff for dirigibles came with the launch of the Graf Zeppelin and its larger successor, the Hindenburg (the length of three football fields). It is no overstatement to say that much of the world fell in love with the ponderous but stately crafts, which Eckener likened to "gleaming silver fish in an ocean of sky."

The dream machines were finally done in by a convergence of harsh realities. As Nazi repression and military ambition alarmed much of the world, Americans took note that the swastika was now painted on the tail fins of the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg. Also, Hitler saw the airships—outpaced by airplanes in speed, ability to fly long distances and payload capacity—as too slow for combat and discontinued government support.

The final blow came with the Hindenburg disaster; the airship burst into flames as it landed in Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937; 35 of 97 passengers died. The cause of the conflagration was not difficult to remedy—a switch from flammable hydrogen to inert helium—but because zeppelins were not deemed essential to the war effort, "most of the intricate frameworks were melted down to make airplanes," Ganz says.

Today, a German firm, ZLT, has revived the zeppelin with a version that is smaller, lofted by helium and dubbed the NT (for New Technology). An American company, Airship Ventures, based out of Moffett Field, California, now flies one of the next-generation craft on sightseeing excursions.

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article stated that Airship Ventures was based in Napa, California. This version has been updated.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)