Eight Artists Conspire About Water Issues In a New Exhibition

In Omaha, Nebraska, individuals and nonprofits unite in a show focusing on the issues of water quantity and quality

A contorted web of blue painter's tape stretches across a warehouse wall in the Old Market District of Omaha, Nebraska. The lines represent the major rivers of the state: the Platte, Loup, Elkhorn, Niobrara and more, all draining to the great Missouri, which delineates the state's eastern border.

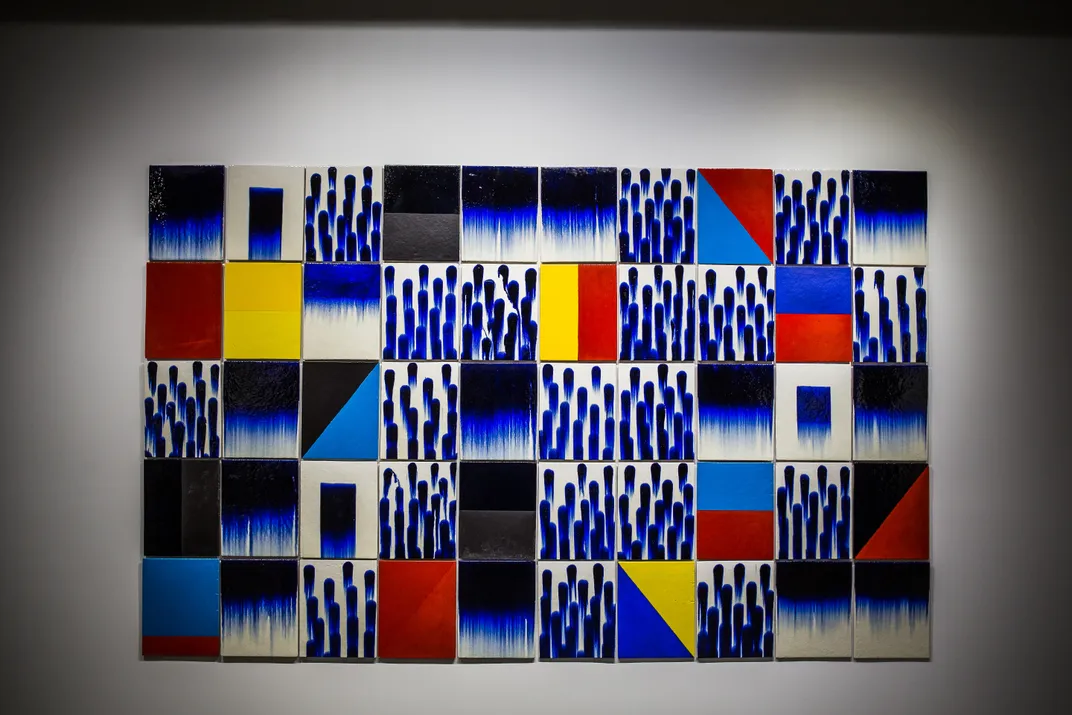

Connecticut-based artist Suzan Shutan drew on more than just the artistic appeal of the shape of these rivers. She scrupulously placed more than 600 pom-poms, with the help of high school students, representing water testing in wells around the state, amid the bends and branches of the waterways. Some tests come back with pollutants at levels higher than federal guidelines recommend, and she color-coded the pom-poms to mark the presence of these contaminants. Two in particular come from the state’s impressive agricultural industry. Nitrates run off of fertilized fields and make their way into drinking water, as does the herbicide atrazine, made by Syngenta, that is applied to corn. Atrazine disrupts hormones in frogs, and some researchers suspect it might harm humans.

The result is striking: "You are looking at this map, it's beautiful, soft, whimsical and playful," says Michael Hollins, program director at Kaneko, the open space devoted to creativity, where the piece is currently on display. People like to touch the fuzzy pom-poms as they explore the artwork, but then some notice that the wells closest to their homes have nitrate or atrazine levels that are shockingly high. "It is scary," Hollins says, but he hopes that the shock translates to better awareness of local water issues.

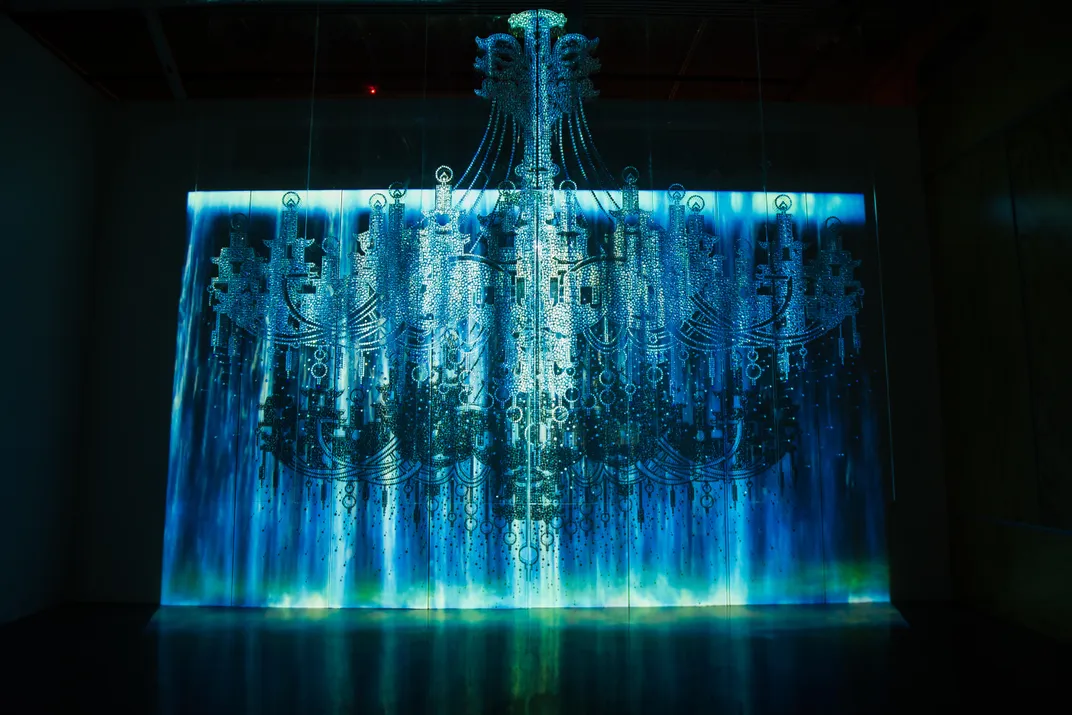

Kaneko’s newly opened “Water” exhibition, like all of the space’s shows, spans many disciplines. Artists, scientists, local nonprofits and others came together to examine issues of water quantity and quality. From wire sculptures of native fish to a kinetic sculpture paying homage to the state's ubiquitous center pivot—an irrigation structure that gives rise to the patchwork of irrigated circular fields inscribed within the precise grid of midwestern rural roads—“Water” explores its subject with a uniquely local lens.

The exhibition comes at a particularly poignant time, Hollins says. The ongoing drought in California, floods in India and toxins in the drinking water for Flint, Michigan are just a few recent crises that have emphasized humankind's fragile control over the water we need.

Nebraska, like all regions, has plenty of water concerns. The state is blanketed by more than 45 million acres of agricultural land, mainly used to grow corn for grain, soybeans, hay and wheat as well as graze cattle, reports the U.S. Department of Agriculture's 2012 Census of Agriculture, and about 44 percent of that land is irrigated. Nearly 24,000 miles of rivers and streams provide a major source of drinking and irrigation water, complemented by water pumped from underground aquifers, including the vast Ogallala Aquifer.

Those water resources make Nebraska comparatively water wealthy, reports David Hendee for the Omaha World-Herald. Water-stressed California has started to eye Nebraska's waters with the intention to buy—a reminder that issues of water scarcity as well as quality affect even the water-rich regions.

The show, which runs through April 23, features visual artwork by eight artists and exhibits or demonstrations by more than a dozen local nonprofits. The two themes of water quality and quantity emerged over the two years of the show’s collaborative development, says Hollins. The Kaneko’s commitment to feature local organizations and artists, where possible, helped focus the show. “Water is such a huge sprawling topic,” Hollins says. “There are so many themes that could and should be discussed.” But by highlighting the local community’s efforts, he aimed to show how people face similar water problems around the world. The juxtaposition of abstract, symbolic art and real world technologies should surprise viewers and get them to think about and appreciate the importance of water.

Artist Susan Knight grew up in Michigan, surrounded by the Great Lakes, so it seems natural that water should figure prominently in her sculptures. Water does that. The ponds, creeks, lakes, and shorelines of childhood seem to have the power to cut not only through rock and soil but through the soft folds of the brain, where they inscribe themselves in memory and feeling.

When Knight moved to Nebraska, she soon realized that her desire to tell water stories shifted from a focus on the Great Lakes to the rivers and groundwater of her new home. "Water issues are global, but like politics, everything is local," she says.

Knight’s work features intricately cut spirals and shapes made of paper, Mylar, plastic and Tyvek, draped from ceilings and adhered to walls or even suspended temporarily in the branches of trees. She has two different pieces in the “Water” exhibition. In “Water Bank Boogie,” she explores the complex subterranean structure of a riverbank and its soil types with colorful cut Tyvek and paper shapes that evoke jellyfish, umbrellas or bells.

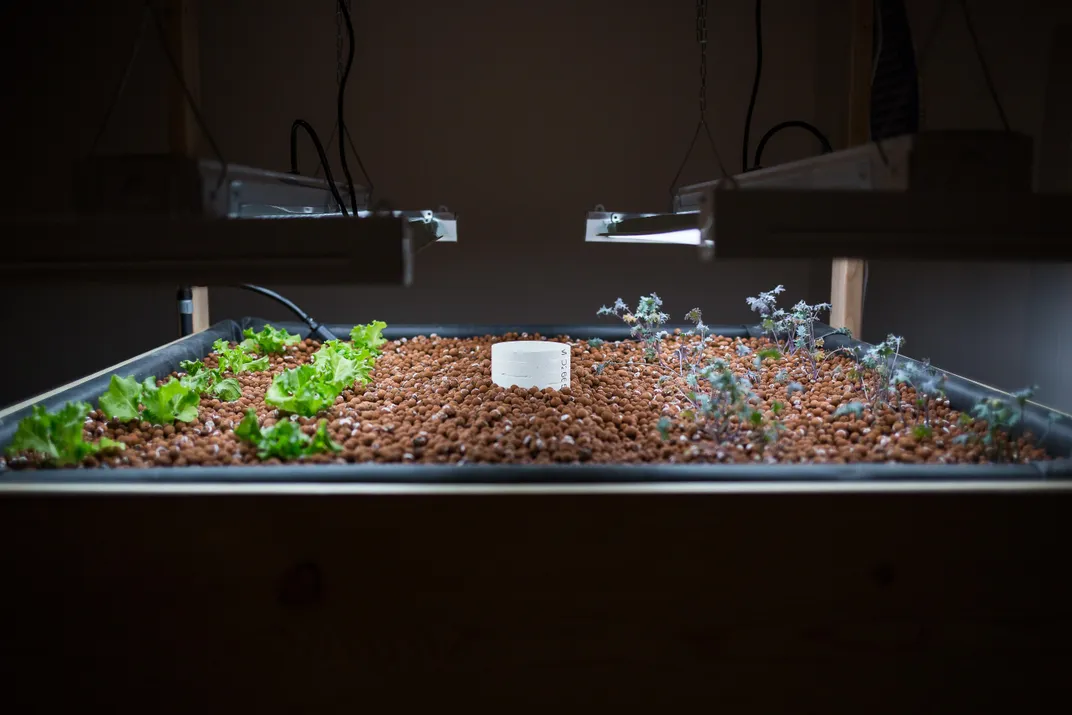

Another piece, “Hidden Magic,” sends curlicues of white paper twisting down from the ceiling and reaching toward the viewer. Inspired by rain gardens, the work calls to mind the roots of plants. Researchers at the University of Nebraska in Omaha are encouraging urban and suburban residents to plant specially designed gardens that will capture and soak up rainfall while reducing runoff that carries pollutants from streets to rivers. Even though aquifers undergird the state, being smart about water is a vital strategy to avoid depleting those life-giving resources.

The artist often consults with scientists and researchers when she is developing her pieces. She worked with landscape architect Steven Rodie, also a professor and director of the University of Nebraska Omaha’s Center for Urban Sustainability, to better understand how the gardens work. The roots of native plants such as marsh marigold, prairie blazing star, big bluestem grass and more all penetrate the soil to different depths and actually provide conduits for rain and storm water to soak through the earth, Knight explains. With her work, she says, "I wanted to make visible what nobody sees, what takes place underneath the surface."

That desire seems to be a theme in Knight's work. All of her pieces, many visible on her website, first demand that the viewer lean in to appreciate the movement, color and form. "Then with that attention I can talk about my focus on water and making it clean and healthy," she says.

The “Water” exhibition does the same thing. "We wanted it to be a positive show, not just focusing on the ominous and overwhelming, but also looking at how creativity is being used by both scientists and artists," says Hollins. With creativity, he adds, people can come up with solutions to the problems that plague us.

“Water” runs through April 23 at the Kaneko in Omaha, Nebraska. The program will also feature a guest lecture by Tyrone Hayes, a professor at University of California, Berkeley, whose work has investigated water contamination by atrazine; an ongoing conversation series; and a day of water-themed family activities based around water.