Stunning Black-and-White Photos of the Nazca Lines

Edward Ranney’s photographs of the famous Nazca Lines show the mysterious geoglyphs from an unusual angle—eye-level

The Nazca Lines have puzzled the world since Peruvian archeologist Toribio Mejia Xesspe discovered them in the 1920s. Now they are back in the news after Greenpeace activists added a note to the famous geoglyphs during recent climate talks. Ignoring law that prohibits entrance to this delicate portion of the Peruvian desert, activists laid out cloth letters reading "Time for Change! The Future is Renewable. Greenpeace." Though the activists claim they were careful to not disturb anything, the area they entered is off-limits without a permit and special shoes: the ground around the lines is simply too dry and fragile to be trod upon without first taking painstaking precautions.

One man who knows a thing or two about the fragility of the lines—and the delicate act of both documenting and preserving them—is Edward Ranney, a photographer whose book The Lines, released last August, catalogs the mysterious geoglyphs of the Nazca culture in Peru, as well as cultures in Chile's Atacama Desert, in stunning black-and-white photographs. Ranney has been photographing archeological sites and ancient, pre-Columbian architecture in Peru and Mesoamerica since the 1960s.

"A lot of people are really outraged, and rightly so," Ranney says of Greenpeace's actions. "Any time anyone walks on the pampa, those footprints don't go away—[the lines] are there because it never rains there. It brought a lot of attention suddenly to the lines, to the Nazca, but it did so in a very unfortunate way."

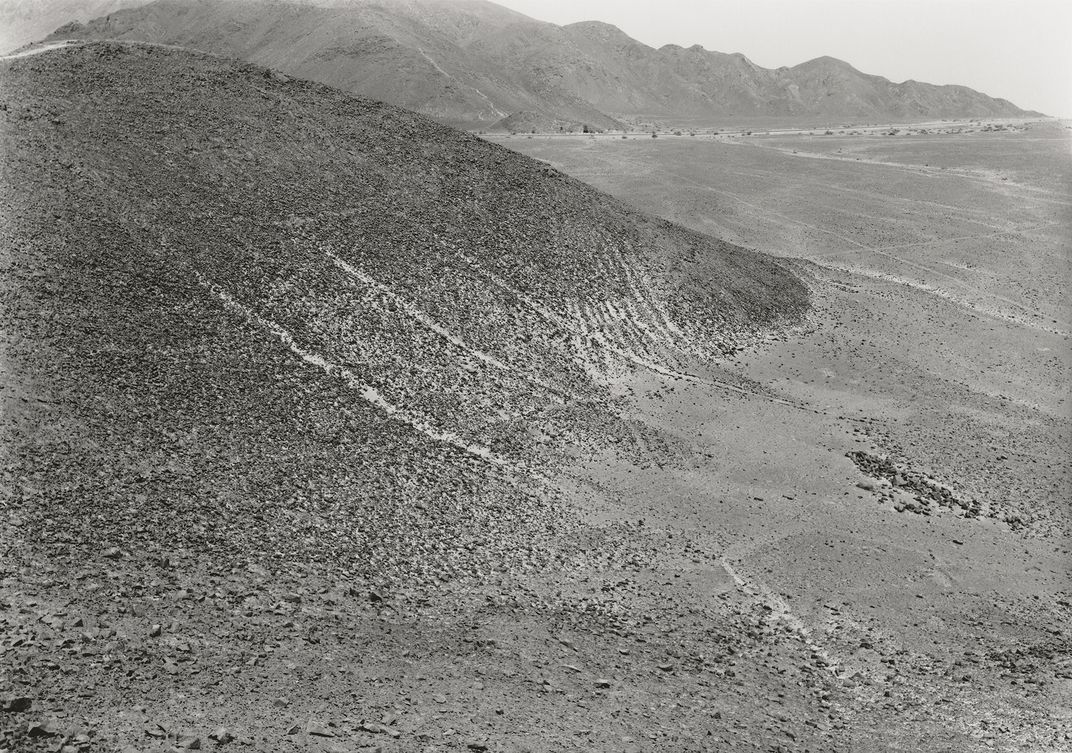

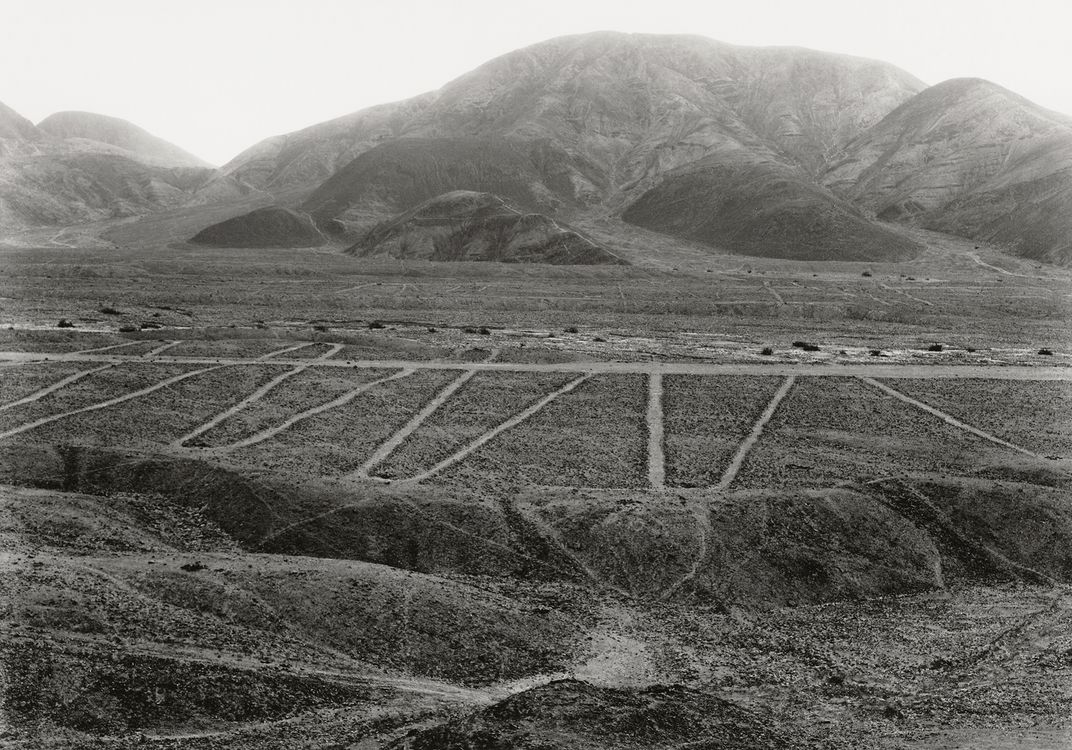

The Lines looks at the famous Nazca geoglyphs—scratched into the desert more than 1,000 years ago—from a unique perspective: ground-level. Most photographs show the geoglyphs from an aerial view, emphasizing their scale (some are as large as the Empire State Building). Ranney's photos instead show the lines as someone from the Nazca culture, using the lines for religious reasons, might have encountered them.

"Most of the pictures that we see of the lines are taken from airplanes, and it emphasizes the graphic nature and real mystery of how these things came into being," Ranney says. "My interest, because I couldn't get high enough to photograph from the air, was the foothills. I wanted to stick to working to the ground. And I found that the more I saw different patterns, the more intriguing it became, because these lines really change the landscape. For a landscape photographer, it's an exciting project to go into these areas and work in these spaces that is somewhat forbidding and most contemporary travelers don't even get near."

The Lines (Yale University Art Gallery)

Ranney began The Lines as part of a much broader survey of ancient architecture along the Peruvian coast in 1985. He quickly realized that these desert areas fit perfectly into the canon of work he had been producing since a 1964 Fulbright trip: recording ancient, previously unarchived architecture and sites.

"I realized that no one had looked at this [area] visually and tried to create a fairly comprehensive archive of sites in black-and-white photographs that could stand as references and also as their own artwork," Ranney explains.

The Nazca lines aren't the only ancient structures Ranney has photographed. A new exhibition at the New Mexico Museum of Art, North to South, celebrates Ranney's career of photographing Inca and Maya cultures. The show, on view until April 19, includes more than 40 images from his decades of travel and work—work that, to Ranney, is far from complete.

"There's continual research in the Andean region, which is really exciting because there is more and more discovered every year," Ranney says. "That's why I continue to photograph, because my survey is not yet done."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)