A 160-Year-Old Photographic Mystery

In 1851, Levi Hill claimed he invented color photography. Was he a genius or a fraud?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-daguerreotype-Levi-Hill-631.jpg)

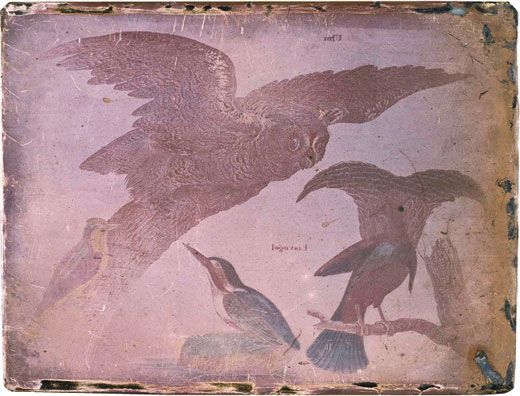

“There, do you see it?” she asks, holding up a small, silvery rectangle in the half-lit room.

For a moment, I do: a splash of blue on a bird’s wings. Then it disappears.

The photograph, captured some 160 years ago, reveals the outline of an owl and three smaller birds.

Lifting another plate from a storage box labeled “Hill, Levi,” Michelle Delaney sighs as she examines it.

“Oh, that makes me sad. You used to be able to make out the outline of the village in the center here, but it’s faded even more now,” she says. I see only a blur of brown, gray and white; what a ghost might look like caught on camera.

In a sense, that’s what Delaney, 44, curator of the National Museum of American History’s photographic history collection, has been chasing the past three years: the ghost of the Rev. Levi L. Hill. In the years since his death in 1865, a few historians praised Hill as the unacknowledged inventor of color photography. (A Scotsman, James Clerk Maxwell, is generally credited with producing the first successful color photograph, in 1861.) Most, however, concluded that Hill was a hoodwinker.

Hill was a Baptist minister in West Kill, a tiny town in the foothills of New York’s Catskill Mountains, when he began experimenting with daguerreotypes, an early form of photography. In February 1851, Hill made an astonishing claim: “I now have forty-five specimens, all of which present the several colors, true to a tint, and with a degree of brilliancy never seen in the richest Daguerreotype,” he boasted in a letter to the Daguerreian Journal, the first commercially produced photography magazine. He vowed to continue experimenting until he “perfected the discovery” and assured fellow photographers that, after patenting the process, he would share it with all of them for a “reasonable” price.

The journal’s editor, S. D. Humphery, lavished Hill with praise, christening his invention a “Hillotype.” But the fervor soon soured. Hill had promised a public demonstration of his works and process, but he kept pushing the date back.

Hill had tried—and failed—to patent his method. An 1853 government document stated that “existing patent laws would not afford to the inventor the security required” for his chemical process. Hill turned his back on photography altogether in 1855 after his wife and research partner, Emmeline, died at age 38.

He did finally publish his ideas in an 1856 volume titled A Treatise on Heliochromy, but by then, says Delaney, most of his peers “had thoroughly dismissed Hill’s work as fakery.”

By the time he died nine years later, obituaries referred to his Hillotypes as a failed experiment.

“Hill had a lot of supporters and a lot of naysayers,” says Delaney. Hoping to resolve the question of what Hill actually accomplished, she teamed up with independent conservator Corinne Dune and experts from the Getty Conservation Institute and George Eastman House. They analyzed the Smithsonian’s collection of 62 Hillotypes, using the latest methods of spectroscopy to identify materials and pigments without damaging the works. What they found largely vindicated the inventive clergyman.

“There’s limited color, but a wide enough range to see that he was successful,” Delaney says. But the project’s researchers also discovered that some of Hill’s works had been hand-colored or enhanced.

Delaney, who is still researching Hill, plans to include a chapter about him in a book she is writing about early American photography. “I think his legacy is that he really inspired people, in both America and Europe, to go forth and work with color processes,” she says.

She has made two visits to West Kill to consult local historians and archives, and hopes to track down more of Hill’s work, since his logbooks show he was prolific. She is particularly curious about the contemporary European art prints Hill often used as photo subjects.

“West Kill is still basically a one-block town, so I’m thinking, where did he get all those European prints?” And, she wonders, “How would someone not trained in chemistry learn to do this stuff?”

At the very least, he was a colorful character.