A 21st-Century Reimagining of Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms”

The iconic paintings helped the U.S. win World War II. What do they mean today?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/77/7777011b-9809-445d-9ef7-2b7a84b3548f/web4covsopen.jpg)

E. B. White penned immortal lines for spiders and piglets, but the author of Charlotte’s Web failed to make Franklin Roosevelt’s rhetoric come to life.

Hoping to stoke enthusiasm for American involvement in World War II, Roosevelt delivered an address to Congress in January 1941 that laid out the humanitarian values at stake: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear.

The public response? Crickets. Congress barely applauded. The next day most newspapers didn't even mention the “Four Freedoms.” Those who were still talking about the phrase in the weeks and months that followed did so to lambaste its “hollow, empty sound.” The government hired White and other A-list scribes to drum up some buzz, but White’s boss called his pamphlet “dull.” The “Four Freedoms,” in the words of one federal administrator, were a “flop.”

Then Norman Rockwell picked up his paintbrush.

Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms,” printed in four successive issues of the Saturday Evening Post in 1943, instantly hit home. Employing the painter’s own very ordinary Vermont neighbors as subjects, the folksy illustrations packed more emotional wallop than Roosevelt’s soaring oratory two years earlier.

Roosevelt’s spin doctors had always been perplexed that some wartime sound bites caught on while others did not. Though lacking the poetry of “a date which will live in infamy,” the “Four Freedoms” was carefully crafted, employing catchy alliteration and enumeratio, the classic rhetorical device of dividing a big idea into numbered parts. But “freedom itself is hard to understand, and now you have four of them,” says James Kimble, co-curator of the Norman Rockwell Museum’s new traveling exhibition, “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms.” To complicate matters, other politicians and organizations tacked on their own pet freedoms, such as “freedom from fear of old age” and “freedom to establish schools that teach the realities of life.”

Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms: Images That Inspire a Nation

This book tells the fascinating story of the creation and response to Rockwell's Four Freedoms.

Rockwell, too, had found Roosevelt’s formulation to be a snooze. “The language was so noble, platitudinous really, that it stuck in my throat,” the painter remembered. Yet as he “juggled” the idea in his mind images emerged; he saw a way to help the war effort. Rockwell traveled to Washington in 1942 to propose paintings based on the speech, but officials there, perhaps sick of flogging a dead concept, said there was no money in the budget and suggested that Rockwell illustrate a Marine Corps calisthenics manual instead.

Thank goodness for Freedom of Speech. When Rockwell mentioned his idea to Saturday Evening Post editors, they readily approved the project—Rockwell was their star cover artist. Only after the magazine published the pictures did the Washington propagandists catch on. The Office of War Information, by now being infiltrated by image-savvy, “Mad Men”-style advertising executives, arranged a 1943-’44 national tour for the paintings, which raised almost $133 million in war bonds. Millions of reprints appeared everywhere—inside taxicabs, on milk bottles and stuffed inside Americans’ monthly bank statements, for starters. When the traveling paintings reached a new city, parades shook the streets.

Rockwell’s scenes gave people “something they could remember,” says Kimble, an associate professor of communication at Seton Hall University. The paintings also satisfied America’s changing media appetite. Roosevelt had mastered the fireside chat, but the country was increasingly looking to art from Hollywood and beyond. “It’s still a generation that listens, tuning in by the millions to hear speeches,” says Harvey Kaye, author of The Fight for the Four Freedoms. “But they are also a highly visual generation in terms of movies, magazines with splashy covers, comic books.”

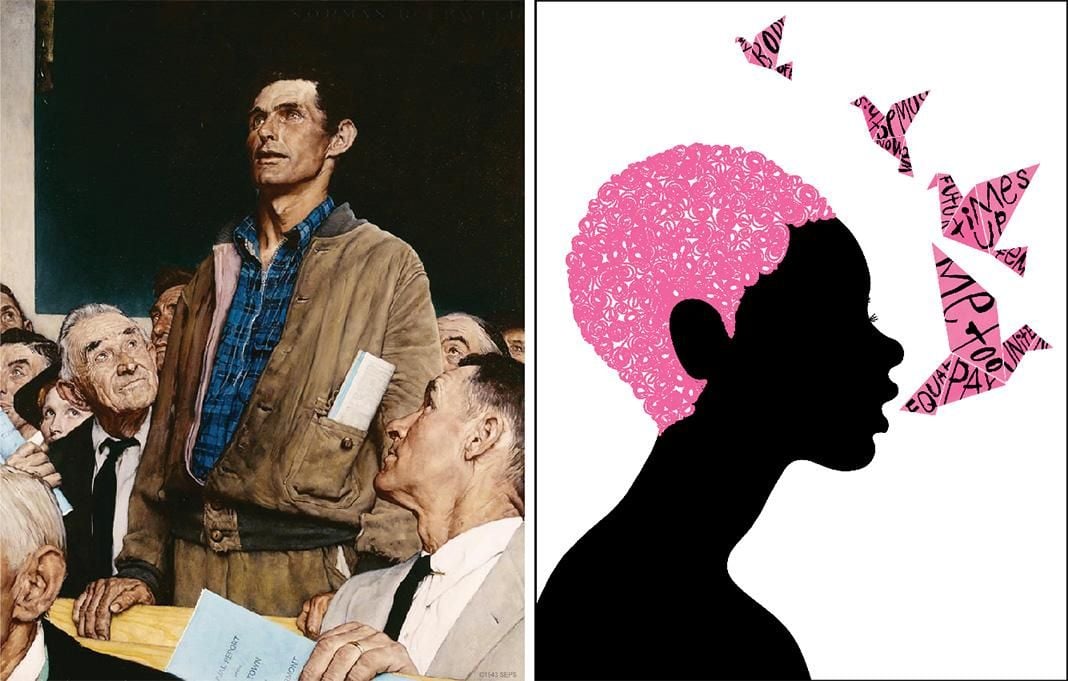

It wasn’t just that Rockwell’s timing was good. Arthur Szyk, a marquee illustrator for Collier’s who signed some paintings “FDR’s soldier in art,” also illustrated the “Four Freedoms.” But his works, featuring a knight, failed to win over the public. A nod to vanished chivalric times, “they were a little remote,” says Stephanie Plunkett, curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In contrast, Rockwell “felt that what people needed was some understanding of how these ideals applied to their own lives. He wanted to show what we had to protect, and what we were fighting for.” So he depicted the American day-to-day. For Freedom of Speech, he drew on a town meeting that he had attended, where the crowd listened respectfully to a lone dissenter. To nail down the especially elusive Freedom from Want—a kind of ideological double negative—Rockwell laid out a Thanksgiving dinner, with a turkey so real-looking that it’s no surprise to learn that he later ate it.

Rockwell’s conjured world is particularly powerful when considered alongside totalitarian art. Hitler used vivid propaganda to vilify Jews and glorify Aryan warriors. “The Nazis wanted to show the master race,” says propaganda expert Steven Heller. Rockwell “wanted to show the democratic ideal.”

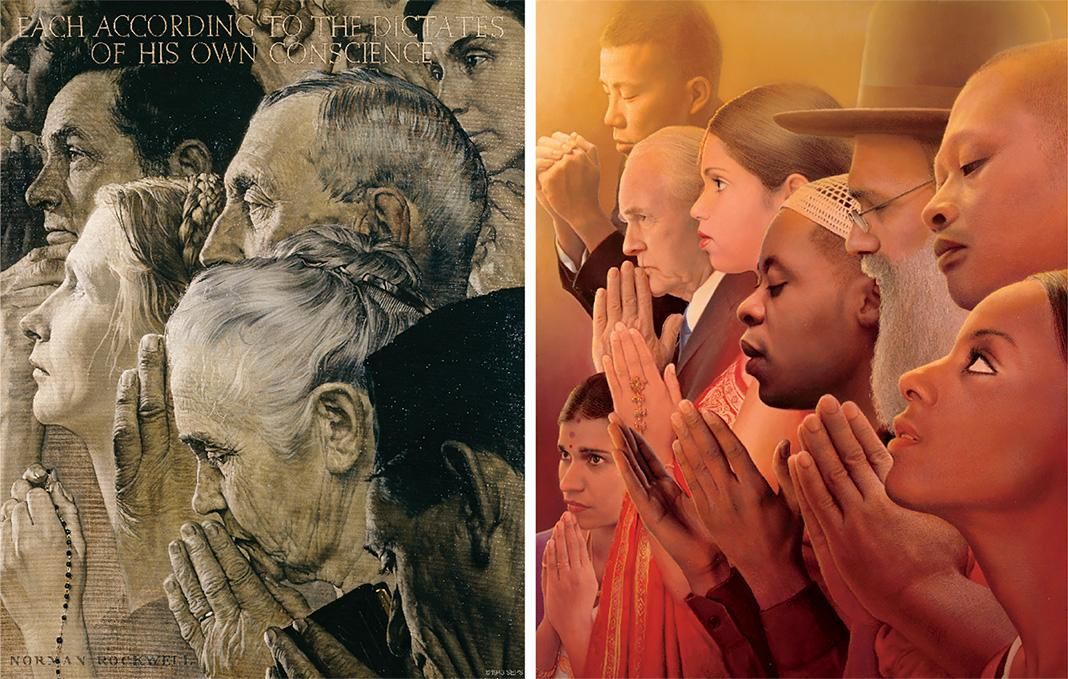

Our democracy looks much different today. In the 1940s, the United States was almost 90 percent white; today, racial minorities make up more than a quarter of our population, and by 2044, the Census Bureau predicts, the United States will be a minority-majority country. Religious views have also changed. In Rockwell’s day there was still a Protestant consensus and about 90 percent of Americans were Christians; today’s spiritual modes are much more varied. Rockwell did make some effort to depict people of different ethnicities and religious backgrounds—no small feat in his homogeneous Vermont town. (He reportedly persuaded an Episcopalian neighbor to pose as a “Catholic for a day.”) But his subjects are overwhelmingly white, with men usually in the foreground. Indeed, Rockwell used one white male model—his neighbor Jim Martin, who appears as the father in Freedom from Fear—as a common thread throughout all four paintings.

In this new, more diverse America, it’s harder to imagine a single figure linking multiple works of patriotic art—or even, for that matter, a single painter who could capture our increasingly complicated ideas of freedom. To celebrate the 75th anniversary of Rockwell’s indelible works, Smithsonian asked four artists to reconsider the “Four Freedoms” for 2018.

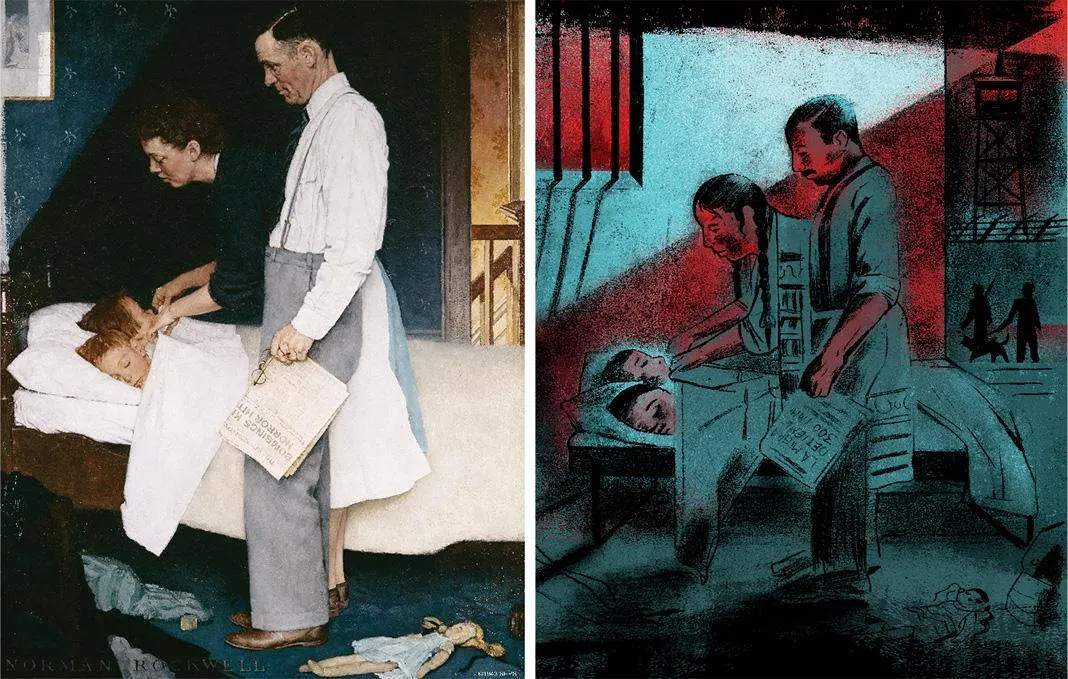

As Rockwell did in 1940s New England, the artists started with what they knew. Tim O’Brien, updating Freedom of Worship, painted people of different backgrounds and religions like those he sees every day in his Brooklyn neighborhood. Ryan Schude photographed his own extended family in his remake of Freedom from Want. They are free from want, like the family sitting down to a turkey dinner in Rockwell’s painting, but they are not free from desire. Rockwell’s vision was one of making do and togetherness, but the world Schude captures is one of excess and distraction.

Contemplating the “Four Freedoms,” today’s artists “juggled” many ideas and questions. Does everyone in the country have the right to live without fear—or just those with legal citizenship? We see a dystopian answer in Edel Rodriguez's version of Freedom from Fear. An immigrant family huddles in a detention center, guards outside the door. These parents, too, tuck their children in, but the fear is palpable.

And can you extend the freedoms you enjoy to someone who doesn’t look like you, think like you, or worship like you? In reimagining Freedom of Speech, Melinda Beck gives the floor to a lone black woman. There is no crowd respectfully listening, as there was for the man in Rockwell’s painting, but that does not silence her. She is here today to claim her “Freedoms”—the promise of Roosevelt’s rhetoric fully realized.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misquoted Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speech after the Pearl Harbor attack. It should be “a date which will live in infamy.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.