Pint-Sized Lizards Trapped in Amber Give Clues to Life 100 Million Years Ago

The trove of Cretaceous reptiles includes an early relative of the chameleon—the oldest yet discovered

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/16/0016265c-ff08-4b60-9beb-f035f0a11fbb/amber_collection.jpg)

Nearly 100 million years ago, the tropical forests of the mid-Cretaceous period were hopping—winged beasts commanded the skies, large reptiles swaggered on land and insects buzzed around flowering plants that were just starting to flourish. Yet until now, little was known about small tropical lizards, whose fragile bones quickly disappeared when buried in the damp forest floors.

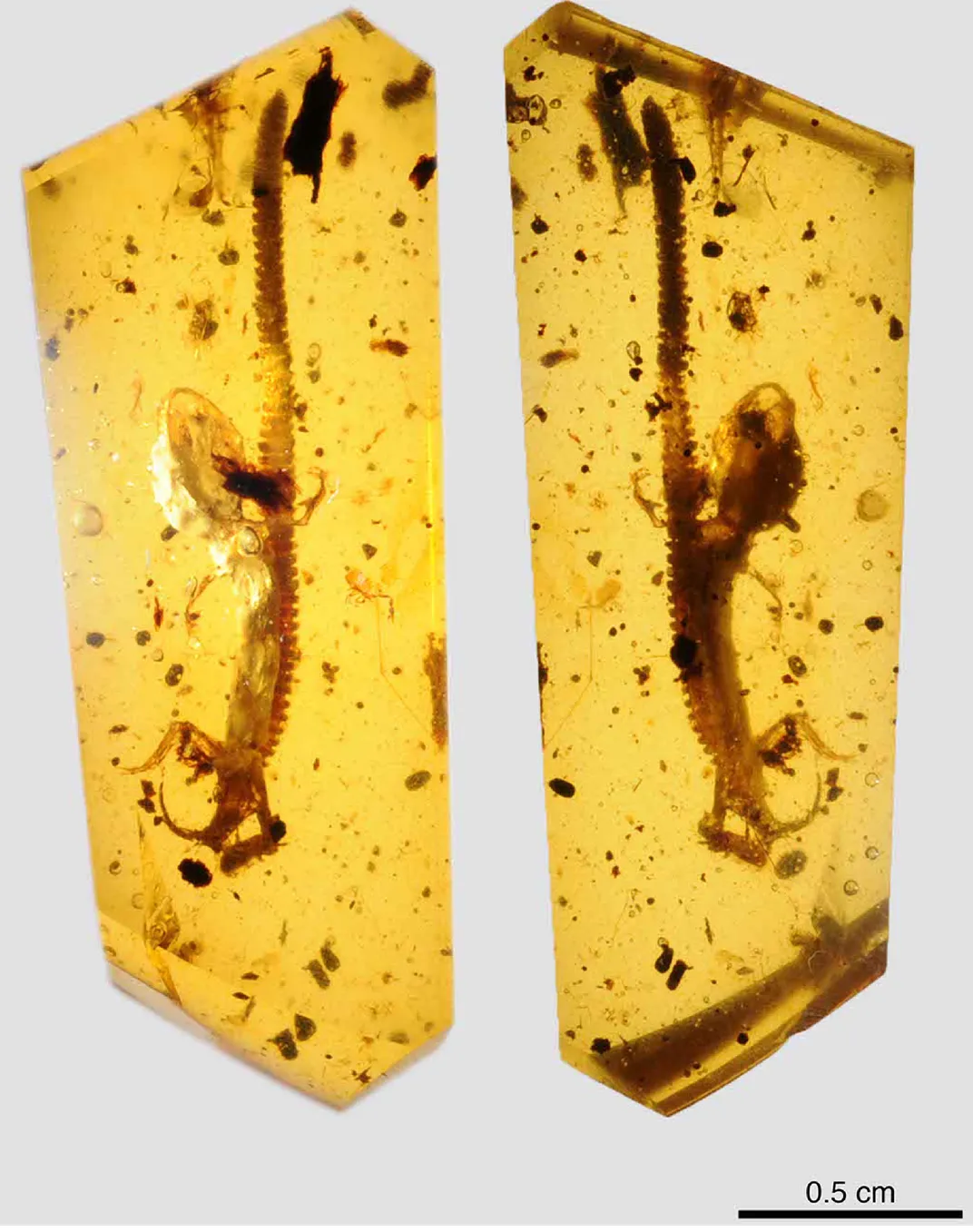

Now, scientists sifting through museum collections have described a dozen of these pint-sized reptiles all entombed in amber. The hapless lizards were caught in the sticky resin of ancient coniferous trees and remained suspended until the present day—several in exquisite condition with claws, bones, teeth, toe pads and even scales intact. These spectacular fossils give scientists a peek into life of the diminutive denizens of the mid-Cretaceous.

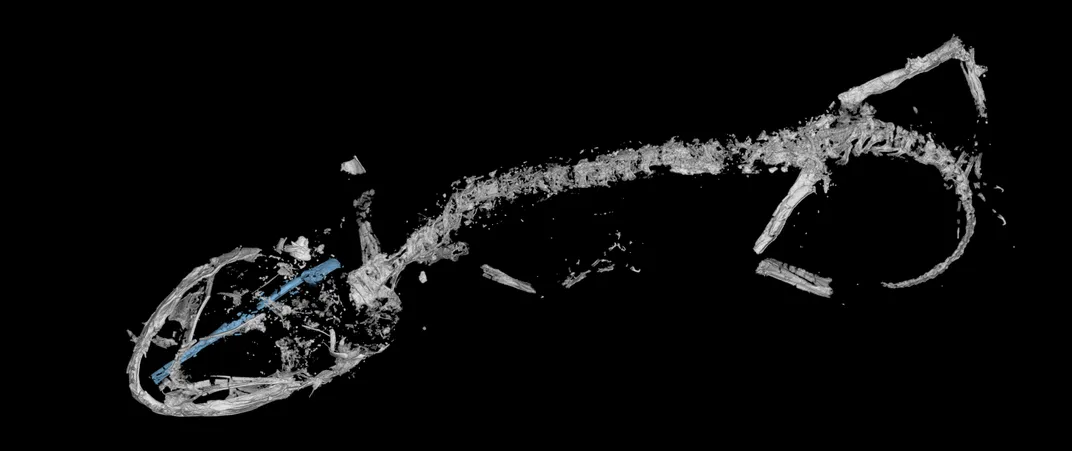

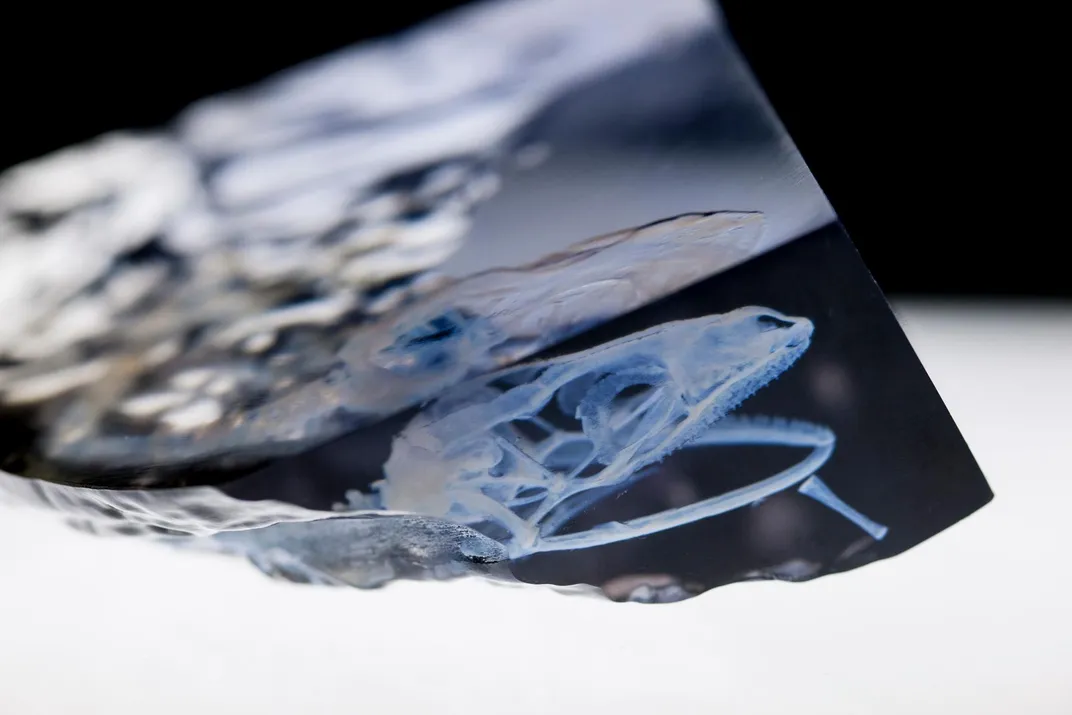

The fossils were actually discovered decades ago in a Burmese mine but remained in private collections until they were recently made available for study through the American Museum of Natural History, which gave scientists access. Using CT scanners to image the fossils, the researchers could “digitally dissect” the lizards without harming the amber droplets, says postdoctoral student Edward Stanley, co-author of the new paper.

What did they find? “A nice smattering of diversity,” he says.

The set includes creatures similar to modern-day geckos and chameleons, as well as a range of species that sport a mash-up of features from both ancient and modern reptile relatives, according to the study published Friday in Science Advances. These animals help fill in the patchy evolutionary history of pint-sized lizards.

“This diverse lizard assemblage shows that back in the day, the tropics were as lizard-friendly as they are today,” says Stanley.

Such wide variation is not necessarily unexpected, says Kevin de Queiroz, curator of the reptile and amphibian collection at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. “There’s a fair amount of diversity in the tropics now,” he says. “So it’s not too surprising that they’ve been diverse in the past.”

Even so, capturing this diversity in the fossil record is less common, says de Queiroz. The fossil record is strongly biased to large animals living in particular environments that can preserve creatures after their death, like deserts or riverbeds. The damp, hot climate in the tropics rarely preserves small and delicate fossils—unless the unfortunate creatures become trapped in tree resin. This ancient group therefore paints a much more complete picture of minute mid-Cretaceous reptiles than scientists have seen before.

One of the reptiles, a dime-sized baby relative of the chameleon, is the oldest discovered representative of that lineage, beating out the previous title-holder by nearly 80 million years.

Chameleons’ closest relative is the agamidae—a group that includes the bearded dragon lizards. Based on genetic evidence, chameleons were thought to have split from these relatives around the mid-Cretaceous period, but fossil evidence from this time had been lacking until now.

The fossils also help sort out when many of the modern reptile traits appeared. The tiny chameleon-like fossil shows early development of the lizards’ ballistic tongues—evidenced by the presence of a large bone that supports the modern chameleon’s sticky weapon, says Stanley. But the fossil did not have the specialized claw-like fused toes modern chameleons use to hang onto branches. Similarly, one of the gecko relatives has preserved toe pads with the modern designs already present.

“We actually have a really good representation of what we have today,” says Stanley, “[just] 100 million years ago.”

Editor's Note 3/14/2016: This article has been updated to reflect that the fossils were not actually donated to the museum, but are still held in private collections. In an e-mail, however, the museum noted that one private collector recently offered to donate several specimen. In addition, the nicely preserved gecko is on long-term loan and they expect that it "will definitely be deposited in a major natural history museum, likely the AMNH."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)