The Changing Face of Bhutan

As the last Himalayan Buddhist kingdom cautiously opens itself to the world, traditionalists fear for its unique culture

On rural highways in Bhutan, trucks hauling huge pine logs rush past women bowed beneath bundles of firewood strapped to their backs. In the capital of Thimphu, teenagers in jeans and hooded sweat shirts hang out smoking cigarettes in a downtown square, while less than a mile away, other adolescents perform a sacred Buddhist act of devotion. Archery, the national sport, remains a fervent pursuit, but American fiberglass bows have increasingly replaced those made of traditional bamboo. While it seems that every fast-flowing stream has been harnessed to turn a prayer drum inside a shrine, on large rivers, hydroelectric projects generate electricity for sale to India, accounting for almost half the country's gross national product.

A tiny nation of 700,000 people positioned uneasily between two giants—India to the south and China to the north—Bhutan was almost as isolated as the mythical realm of Shangri-La, to which it is still compared, until the early 1960s, when the first highway was constructed. Now in a sequence of carefully calibrated moves, the last independent Himalayan Buddhist kingdom has opened itself to the outside world, building better roads, mandating instruction in English for schoolchildren, establishing a television network and introducing Internet service. This month, citizens will conclude voting for a two-house parliament that will turn the country from a traditional monarchy into a constitutional one. The elections were mandated by the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, before he abdicated in favor of his then 26-year-old son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, at the end of 2006. Two political parties scrambled into existence after the decree.

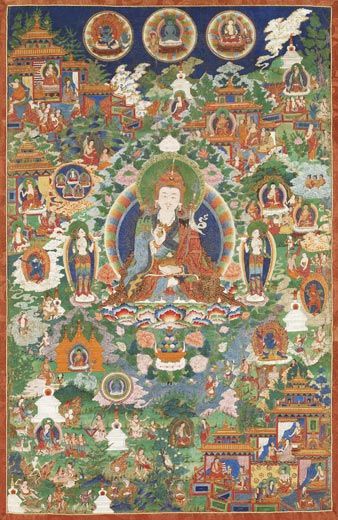

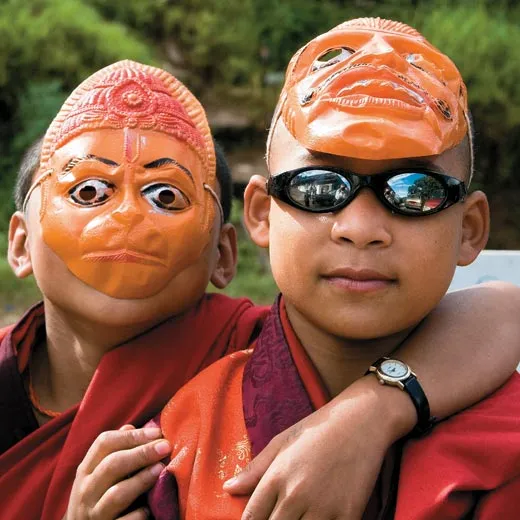

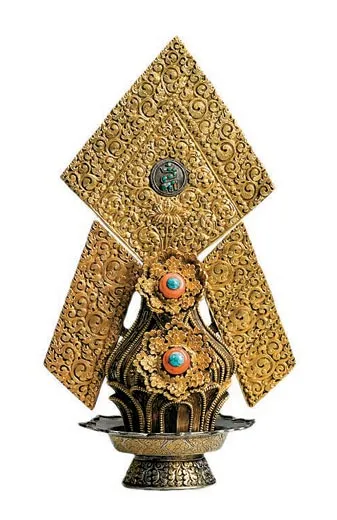

And in another unusual move for the insular country, Bhutan is putting its rich culture on display in the United States in two major exhibitions. The first, which opened at the Honolulu Academy of Arts (February 23-May 23) and will travel to the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, focuses on the country's sacred Buddhist art—not only painting and sculpture, but also ancient ritual dances, known as Cham, which are usually performed by monks to bless onlookers and impart Buddhist teachings. The second showcase is the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival, to be staged this summer (June 25-29 and July 2-6) on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It will include demonstrations of traditional Bhutanese dancing, weaving, metalworking, woodcarving and herbal medicine.

The two exhibitions are part of the centennial anniversary celebration of the nation's monarchy, which was founded on December 17, 1907. More important, Bhutanese leaders hope that the shows will raise awareness of the country's unique culture. "What is required of a small country with a small population is felt ever more strongly with all this globalization," says Dasho Penden Wangchuk, the Secretary of Home and Cultural Affairs. "We feel ourselves a drop in the ocean. And what do we need to survive? Our culture. You want to preserve a plant or the black-necked crane because they are endangered. But [people] are the highest form of living being. The world goes gaga over a particular variety of orchid, but here is a nation. Would you like to see Bhutan disappear?"

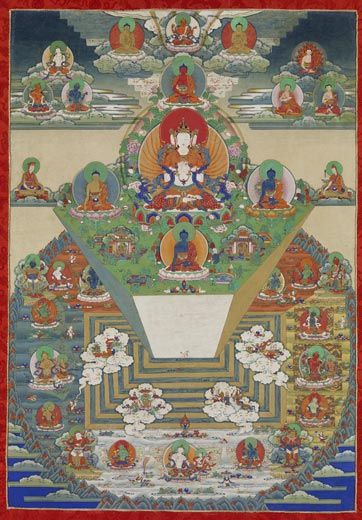

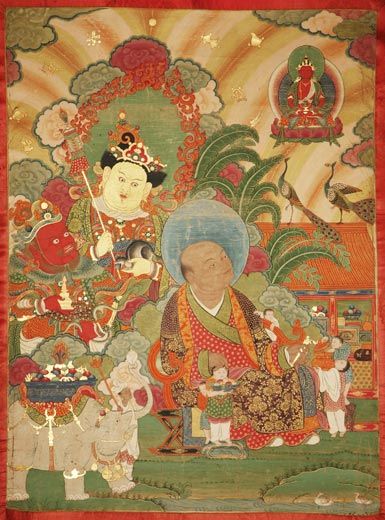

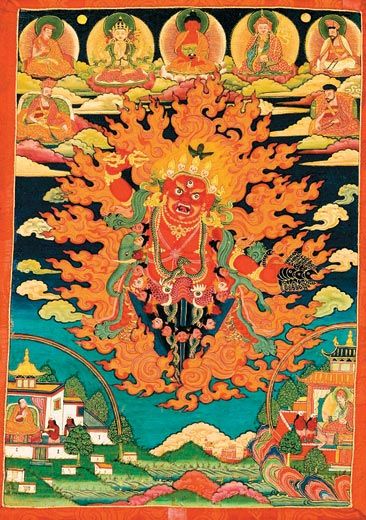

Like much of the country's early history, the origins of the name "Bhutan" are obscure; it may derive from Sanskrit words that mean "end of Tibet." Certain facts, however, are clear. Tantric, or Vajrayana, Buddhism—which employs esoteric techniques as a shortcut to enlightenment—took root in Bhutan in the eighth century through the efforts of the Indian sage Padmasambhava, who traveled widely in Tibet and Bhutan and is reverentially referred to as Guru Rinpoche, or "precious teacher." His influence is everywhere, not only in the many temples said to have been constructed by him and his followers, but also in contemporary jurisprudence. When I asked a former Bhutanese smoker why the country banned cigarette sales (a brisk black-market trade persists), I was told that tobacco is made of the ash of a demoness who was shattered into a thousand pieces when kicked by Guru Rinpoche's horse. Such stories probably began as parables for how Buddhism superseded the animist Bon religion in Bhutan. However, the old gods were never completely effaced. Even today, the Himalayas in Bhutan are regarded as deities, and the Bhutanese government forbids mountain climbing, which has attracted so many tourists to neighboring Nepal.

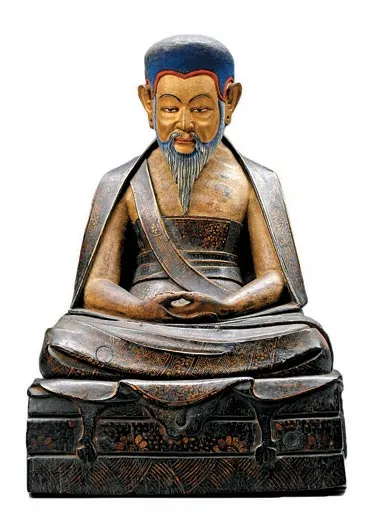

The leader who unified the country in the 17th century, Ngawang Namgyal, is revered today as a saint. Fleeing a power struggle in Tibet in 1616, he settled in western Bhutan, where his particular brand of Buddhism, known as the Drukpa school, was already well entrenched. The charismatic Zhabdrung ("at whose feet one submits"), as he is known, repelled Tibetan armies, subdued feudal lords within Bhutan and began the system of dzongs—the fortresses that combine religious and civil jurisdiction in each district. The characteristic style of Bhutanese architecture, with its bay windows and elevated, pitched roofs, as well as the country's religious rituals and unique dress style (the kimono-like gho for men and kira for women), stemmed from the Zhabdrung's desire to distinguish the country from its expansion-minded neighbor Tibet.

More than anything, though, Buddhism is central to Bhutan's identity. "We believe that Bhutan without Buddhism would not be Bhutan," said Lyonpo Ugyen Tshering, a former Secretary of Labor and Human Resources and now a candidate for the National Assembly. Bhutanese Buddhism flourished for centuries in relative isolation. But the modern world—particularly as seen on television, which arrived legally in the kingdom in 1999—has already produced some undesirable changes. "Acts of violence in the movies, which show so much fighting, have not been so good for our youth," Penden Wangchuk said. "We have had gang fights and youths fighting with each other. This is not a healthy thing. Bhutan stands for peace, tolerance and nonviolence."

Still, most of Bhutan's leaders seem to think that controlled contact with the outside world will be beneficial. Inaugurated in 1974, tourism has since grown steadily; in 2007, nearly 20,000 foreigners visited Bhutan. Travelers are required to make all arrangements through an approved tour operator and spend about $200 a day in the country. This "high-value, low-impact" tourism aims to avoid the experience of Nepal, where hordes of backpackers roam the country without spending much money.

For a religious perspective, I went to Punakha. At an elevation of 4,100 feet, compared with Thimphu's 7,600, this relatively warm town is home to the Buddhist leadership during the winter months. There Thsula Lopen, one of Bhutan's highest-ranking monks, told me that television needn't contradict Buddhist values; in fact, he said, Bhutan now has Buddhist TV shows. (But there is no Nielsen system to measure their ratings against those of the Indian soap operas that have transfixed much of the nation.) "In olden days, there was no communication of our Buddhist religion," he went on, speaking in Dzongkha, the Tibeto-Burman language that originated in western Bhutan and was declared the national language in 1961. "Now, with modernization, I think our religion can spread all over the world."

The monarchy in Bhutan began in 1907, when Ugyen Wangchuck—a well-born governor and general who restored peace and order to the country after a period of civil strife—was named the first king by a group of prominent fellow citizens. Jigme Singye Wangchuck ascended the throne in 1972 when he was only 16 and held power for 34 years. Educated in India and Britain, he is a distinctively Bhutanese blend of the traditional and the progressive: he has four wives (all sisters) and a passion for basketball. Abroad, he is best known for championing what he calls "Gross National Happiness"—emphasizing the value of cultural traditions and a clean environment, for example—over untrammeled development.

He has explained his push to democratize Bhutan as a safeguard against the risk that some future monarch might be incompetent or worse. But his desire to maintain the nation's sovereignty likely influenced his decision. Recent decades have proved disastrous for other Himalayan Buddhist states. Tibet was taken over by China in 1950, self-governing Ladakh was divided between India and Pakistan in 1949 (with China grabbing a portion from India in 1962), and, in 1975, India annexed the kingdom of Sikkim, following a steady influx of Hindu immigrants from Nepal that left Buddhists in a minority. The hope is that a democratic Bhutan would more readily elicit world support if its sovereignty were challenged. "Democracy may not be the best form of government," Penden Wangchuk told me, "but it is the one accepted by the world."

But Bhutan's path to democracy has been bumpy. In the 1980s, perhaps motivated by a desire to avoid Sikkim's fate, the government redefined citizenship to exclude those who could not claim Bhutanese parentage on both sides. Southern Bhutanese, most of whom are Nepali-speaking Hindus, were also required to produce a tax receipt from 1958 (the year a nationality law first defined what it meant to be a Bhutanese citizen). The government said it was attempting to control illegal immigration; southern Bhutanese protested that legitimate citizens were also being forced to leave. For two years, beginning in late 1990, refugees poured out of southern Bhutan and into Nepal, where camps were set up to house them. Today there are some 107,000 people in those camps, although how many are originally from Bhutan remains a topic of impassioned dispute. The U.S. government has offered to accept as many refugees as would like to come to the United States. In the meantime, Maoist groups operating from Nepal have threatened to disrupt the elections. On January 20, four bombs went off in Bhutan; the police said they suspected that Nepal-based Maoists were responsible.

The fifth king, who has already taken charge and will be officially crowned this spring, has not deviated from his father's policies, including the former king's approach to the refugee problem. He also apparently endorses his father's environmentalism. Not only is logging strictly supervised, but a draft constitution, expected to be approved this year by the new National Assembly, requires Bhutan to maintain 60 percent of its land as forest. Yet some citizens worry that the newly empowered electorate's demand for basic services could threaten the nation's remarkable range of native plants and animals. Bhutan boasts 360 varieties of orchids, 650 species of birds and such rare fauna as the snow leopard and the red panda. "If every village has to be connected by roads, electricity and medical facilities, it will not be a very pleasant thing environmentally," said Lam Dorji, executive director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature, a private environmental group. "We are in a fragile mountain ecosystem."

None of the Bhutanese citizens I met seemed particularly enthusiastic about their impending conversion to democracy, an observation with which Dasho Kunzang Wangdi, the country's chief election commissioner, agreed. "People are perfectly comfortable with the way things are," he told me. Both of the political parties vying for control of the National Assembly this month share an allegiance to the royal vision. "We are not starting a party because we have a better vision; we are starting a party because the king has ordered it," said Tshering Tobgay, a founder of the People's Democratic Party. "Do we have an ideology other than we want to continue what the king is doing?" He smiled, amused, perhaps, by the notion that a politician might criticize the king. At least in the short term, a democratic Bhutan may not look so different from the Bhutan of today.

Arthur Lubow wrote about the correspondence between Vincent van Gogh and the artist Émile Bernard in the January issue.