Taking the Great American Roadtrip

In the spirit of Kerouac and Steinbeck, the celebrated travel writer fulfills a childhood fantasy: to drive across his native land

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Los-Angeles-freeway-631.jpg)

The mixed blessing of America is that anyone with a car can go anywhere. The visible expression of our freedom is that we are a country without roadblocks. And a driver's license is our identity. My dream, from way back—from high school, when I first heard the name Kerouac—was of driving across the United States. The cross-country trip is the supreme example of the journey as the destination.

Travel is mostly about dreams—dreaming of landscapes or cities, imagining yourself in them, murmuring the bewitching place names, and then finding a way to make the dream come true. The dream can also be one that involves hardship, slogging through a forest, paddling down a river, confronting suspicious people, living in a hostile place, testing your adaptability, hoping for some sort of revelation. All my traveling life, 40 years of peregrinating Africa, Asia, South America and Oceania, I have thought constantly of home—and especially of the America I had never seen. "I discovered I did not know my own country," Steinbeck wrote in Travels with Charley, explaining why he hit the road at age 58.

My idea was not to linger anywhere, but to keep on the move, as though to create in my mind one long panning shot, from Los Angeles to Cape Cod; to get up each morning and set off after breakfast, going as far as I wished, and then find a place to sleep. Generations of drivers have obviously felt the same way, since the country has become a set of natural divisions, from Los Angeles, say, to Las Vegas, Las Vegas to Sedona, Sedona to Santa Fe—but I am getting ahead of myself.

Speeding east in late spring rain from the Pacific waves lapping at the edge of Los Angeles Airport, disentangling myself from Los Angeles, struggling from freeway to freeway, I was reminded that much of my life has been spent this way—escaping from cities. I wanted to see the glimmering spaces in the distances that lay between big cities, the road that unrolled before me. Los Angeles was a complex set of on-ramps and merging freeways, like a gigantic game of snakes and ladders that propelled me though the bungaloid body of the city to deliver me to Rancho Cucamonga. Beyond the thinner scattering of houses was the sight of bare hills, a distinct canyon and a glimpse of desert as I cruised into Barstow, California. Then I was happy.

I was reminded that first day and every day after that we are a restless nation, rattling from road to road; a nation that had largely abandoned long-distance trains because they did not go to enough places. It is in our nature as Americans to want to drive everywhere, even into the wilderness. The nature writer Edward Abbey decried in Desert Solitaire the fact that access roads were planned for Arches National Monument in Utah when he was a ranger there. Around Barstow, I was thinking of Abbey, who once exclaimed to a friend that the most glorious vision he'd beheld in his life was "the sight of a billboard burning against the sky."

What made Barstow's billboards a peculiar blight was the contrast with everything that lay around them—the landscape that was so stark and dramatic as a brooding expanse of withered shrubs and fat cactuses, the stony roads that seemed to lead nowhere, the bleak and beautiful backdrop that seemed as though no one had laid a hand on it, with lively colorations at a distance and up close so dry, like a valley of bones looking as though they could not support life. I had seen deserts in Patagonia and Turkmenistan, northern Kenya and Xinjiang in western China; but I had never seen anything like this. The revelation of the Mojave Desert was (peering past the billboards) not just its illusion of emptiness but its assertive power of exclusion, the low bald hills and far-off mountains looking toasted and forbidding under the darkening sky.

That sky slipped lower, scattered rain that quickly evaporated on the road, and then gouts of marble-size hailstones swept over the road ahead, like a plague of mothballs. And in that whitening deluge I could make out the Ten Commandments, set out by the roadside in the manner of Burma-Shave signs, You Shall Not Murder... You Shall Not Commit Adultery, like a word to the wise, until the state line into Nevada, and just beyond, the little town of Primm, overshadowed by its big bulking casinos.

I turned off the super-slab to travel the slower parallel road away from the speeding cars. This route took me past Henderson, and its empty malls, and soon up ahead the lights and the tall hotels.

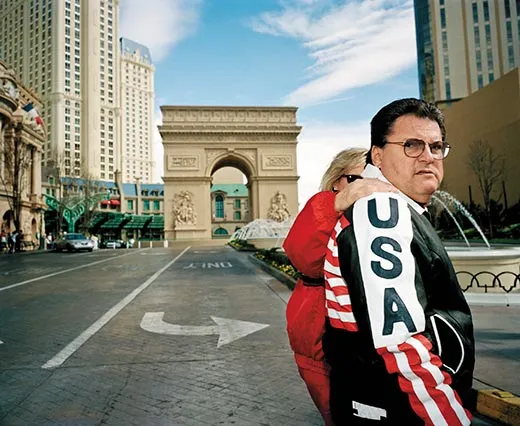

I had never seen Las Vegas before. I was driving down the Strip, which was like the midway of the largest imaginable carnival—a free-for-all, with masks and bingeing. Passing me were slow-moving trucks, pulling mobile billboards that advertised girls for hire and restaurants, magicians, singers, shows. The hotels and casinos were shaped like Oriental palaces, with turrets and waterfalls, and familiarly, the Eiffel Tower, the Great Sphinx guarding a glassy pyramid, the Arc de Triomphe that had the texture of stale cake.

The city of fun houses dazzled me for a day, until my eyes became habituated to the scene, and then I was depressed. Yet Las Vegas is in its way as American as a lobster pot, a lighthouse, a field of corn, a red barn; but it is more. Unlike those iconic images, Las Vegas represents the fulfillment of childish fantasies—easy money, entertainment, sex, risk, elbowroom, self-indulgence. As a city without limits, it can go on spreading into the desert that surrounds it, reinventing itself as long as the water holds out.

No one can satirize Las Vegas; it satirizes itself much more effectively, thriving on self-mockery.

"I was so drunk last night I puked all over myself," a man said to me at breakfast, sounding delighted. "Like I was really drunk. It was great. I didn't know where I was. I just fell down. I don't even know how I got back to my room!"

A manic eagerness penetrated the place, like forced laughter; the object was to have a good time, no matter the cost. I loitered, I nosed in the casinos, I saw the "Love." This show, Beatles songs brought to life on bungee cords and trapezes and high wires, was appropriate to Las Vegas, which is, for good and ill, a circus, but an interactive one, where the visitors are also participants—part-time clowns, floozies, risk-takers. But on a visit to the Liberace Museum on East Tropicana, lured by the lovely hills, I kept going, to Boulder Highway, heading southeast down the open road.

On Route 93, through the mountainous desert, along the Art Deco lip of Hoover Dam, I passed 50 motorcyclists flying American flags crossing the dam and saluting as they did so, another glory of the road.

Less than 100 miles farther, I swung off the road at Kingman, Arizona, which is a crossroads, the Interstate meeting old Route 66. This little town and truck stop was also associated with Timothy McVeigh, the unspeakable Oklahoma City bomber, who used Kingman as a base—he worked here, plotted here and holed up in a local trailer park. Knowing this history gave this road junction in the desert place a sinister aura of anonymity.

This country runs as efficiently as it does because of trucks. They are everywhere. They can go where there are no trains: they penetrate to the smallest towns. And truckers—tough, resolute, willing—constitute one of the great traveling fraternities in America. They know every road.

Did I say "fraternity"? It is also a sorority. The truckers fueling in Kingman that day were mostly women, co-drivers with their husbands. Elaine and Casey were gassing up and grumbling about fuel prices. "I'd make more money baby-sitting," said Elaine, who was headed for New England.

"What do you think should happen?"

Casey, a short, stout woman of 50 or so, said, "I'll tell you. All the trucks stopping altogether—every truck in America—for about four days. That's going to put up the prices of shipping, but it'll make the point."

Twenty miles out of Kingman I obeyed the Watch for Elk sign and turned south off the Interstate on slower, narrower Route 93 toward Wikieup, through butter-colored hills and deep green ravines, and after some miles to an even narrower road that led northeast toward Prescott National Forest. The land was thick with fat, wind-sculpted junipers in my long climb up Mingus Mountain on a switchback road to the 7,000-foot ridge, as far from the stereotype of desert Arizona as one is likely to find.

And another reward on this back road was the old mile-high mining town of Jerome, a restored settlement clinging to the mountainside. In the distance, past Verde Valley, were the almost-dusty pastels, the ochers and purples and pinks and oranges in the smooth cliffs of Sedona. These happy battlements and looming canyons invited me farther off the road, where I found a hotel spa and signed up for a massage.

That was another lesson of the open road: if you don't like what you see in Las Vegas, a day's drive will take you through a natural forest to a pastel paradiso. I would have stayed longer—but this was a road trip, I reminded myself: the journey was the destination.

On my way to Santa Fe, heading east from Flagstaff into New Mexico, the advertised feature of the desert was the crater of a meteorite on the way to Winslow. But really the desert itself was the feature, under a blue canopy of sky. Here and there a Land for Sale sign, with an arrow pointing into the heat-shimmering emptiness; and the sight in the far distance of a tiny dot of habitation, a small house-trailer sitting deep in the desert wilderness, the living symbol of American elbowroom.

Passing a billboard in the desert—"Entering Navajo Country"—I checked my map and saw that the whole of this northeastern quadrant of Arizona is the Navajo Nation Indian Reservation, the Painted Desert visible in the great striated walls of reddish cliff faces at the northerly horizon.

Travel usually implies seeing a place once and moving on; but this became a trip in which I made lists of places I'd return to —Prescott, and Sedona, and now Gallup, New Mexico, where I'd happily go mountain-biking or hiking in the high desert, or visiting the people who possessed the country before we claimed it as ours.

I stopped at the town of Thoreau just long enough to establish whether it was named for the author of Walden and was told that this was not the case—was not even pronounced the same, but sounded more like my own name said correctly (Ther-oo). By late afternoon I was rounding Albuquerque and arrived in Santa Fe in the clear light of early evening.

Santa Fe, mild in May at 7,000 feet, was a monochromatic town of tastefully manufactured adobe. I felt no compulsion to return to Santa Fe. I left the next day, driving through the unexpectedly green and rolling hills, to pick up Interstate 40, old Route 66 with a face-lift. Sixty miles on I used the offramp at Santa Rosa, to verify the unlikely fact that this was one of the more important scuba-diving destinations in the Southwest desert, and also for the pleasure of looking more closely at the small town, glittering in the desert sunlight, bisected by the Pecos River.

At a local diner, I met Manuel and Jorge, of Basque descent, men in their late 70s. They had spent their working lives raising sheep and cattle and were now retired, their children scattered throughout New Mexico. I asked what the town had been like when it was a stop on Route 66.

"Very busy," Manuel said. "And there was more rain then. But now we're in the End Times and everything is changing."

"I have the feeling that you read that in the Bible."

"Yes, I am born again."

"Tell me something about scuba diving here," I asked Jorge.

"It's the best—though I haven't done it," he said. "We have lots of lakes, too."

Farther down I-40, across the state line and looming at lunchtime, was the Texas city of Amarillo, near the center of the Panhandle. I stopped and had a steak, gassed the car again and set off into a different-looking desert, stonier, with clusters of junipers softening its appearance. Nearer Oklahoma, green turned to lush, and then to a great grassy expanse with browsing cattle and tall Texan bushy-boughed trees. Cattle and grassland, trees and meadows, from Shamrock all the way to the border and the even greener pastures of Oklahoma.

Wide-eyed, because it was my first look at the heartland, I saw Oklahoma as a ravishing pastoral, widely spaced towns proclaiming on enormous billboards their local heroes: Erick ("Home of Roger Miller, King of the Road"); Elk City ("Home of Miss America, 1981"). And at Yukon ("Home of Garth Brooks"), I could have hung a left and driven down Garth Brooks Boulevard.

I had always associated this part of America with dramatic weather—tornados, searing heat, thunderstorms. My expectations were met as dark pinnacles of storm clouds massed in the big sky ahead, creamy and marbled at their peaks and almost black below. This was not just a singular set of clouds but an entire storm front, visible in the distance and as wide as the plains—I could not see where it began or ended. The storm was formally configured, as a great iron-dark wall, as high as the sky, bulking over the whole of western Oklahoma, it seemed: the vertical clouds like darkening watchtowers.

This was fearsome and satisfying, especially the croaky weather warnings interrupting the music on the radio. I approached the towering storm and was soon engulfed by hail, wind and dark curtains of rain slashing across the flooded road. There was nowhere to stop, so I just slowed down, with everyone else. After an hour, I had passed through this wall of weather and was entering the dry, sunlit outskirts of Oklahoma City.

This relatively young city—it dates only from 1890—a tidy, welcoming place of broad streets, has a reputation for being God-fearing and hard-working ("Work Conquers All" is the state motto). Since 1995 the city has been known for one traumatic event, the bomb outrage by the murderer Timothy McVeigh, who had drifted here from Kingman, parking a rental truck full of explosives that leveled the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people, many of them women and children. The site was walking distance from my downtown hotel. Surrounded by trees, with some of the bomb-cracked walls still standing, the memorial is the most peaceful and spiritual place in the city.

"Everyone who was in the city has a memory of it," D. Craig Story, a local attorney, told me. "I was 50 blocks away in my office that morning. I had just picked up the phone to make a call. The big window of my office bowed in—didn't break but looked like it was going to turn into a bubble, the air pushing it. The sound of the blast came a few seconds later. Then the news of it."

I said, "This seems like the last place such a thing would happen."

"That was one of the reasons. At first we had no idea why we were chosen for this. But it was because this is such a quiet place. Trust. Good people. No security. Very simple to gain access—to park a truck in a street, even at a federal building, then walk away. We were the easiest target." He shook his head. "So many children..."

Leaving Oklahoma City past the Kickapoo Casino, through Pottawatomie County and the towns of Shawnee and Tecumseh, I came to Checotah and passed a billboard, "Home of Carrie Underwood—American Idol 2005," and wondered whether billboards, like bumper stickers, suggested the inner life of a place. Farther east another billboard advised in large print: "Use the Rod on Your Child and Save Their Life."

The road through eastern Oklahoma was lined with shaggy trees and broad meadows, all the way to Arkansas. The straight, flat, fast I-40, which I'd been using, with detours, all the way from Arizona, now followed the general contour and sometimes the course of the Arkansas River, a major feeder into the Mississippi and the waterfront of Little Rock. Little Rock, the name, had been on my mind since I'd been a boy. It signified racial confrontation, the most divisive American issue of my school days. Black students exactly my age were at first kept from attending Central High when it became integrated in 1957; finally President Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne Division to ensure their entrance.

I drove past Central High, a lugubrious building, then headed to the Clinton Library, looking like a prettified trailer home cantilevered off the bank of the muddy river. But this riverfront, where I had lunch at the Flying Saucer café, was the liveliest part of what seemed to me a melancholy city.

All the way to Memphis I dodged the big scary trucks, and also realized that I had judged Arkansas a little too harshly, because the eastern part of the state was rich in agriculture, with plowed fields and sloping woods, as far as the Mississippi. Monumental in its size and its slowness, meandering through the middle of the great country, the river is a symbol of the life and history of the land, the "strong brown god" in the words of T. S. Eliot, who was born upstream in St. Louis.

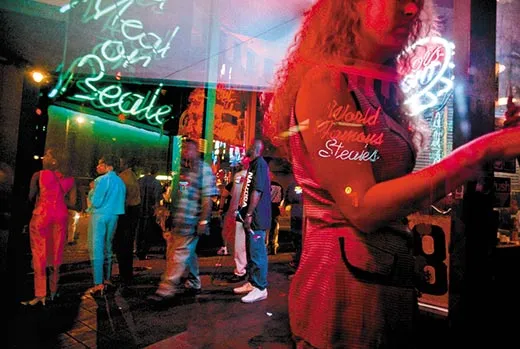

The approach from the west, seeing Memphis grandly arranged on the bluff of the far bank, satisfied my sense of being a romantic voyeur. I found my hotel—the Peabody, famous for its resident ducks; and at the shop in its lobby I met the man who claimed to have sold Elvis his first fancy clothes. Historic Beale Street was just a few blocks away: this quarter mile of pavement, advertising itself as Home of the Blues and Birthplace of Rock and Roll, was also the best place to find a drink and dinner—B.B. King's restaurant and blues club or the Pig on Beale farther down the block.

By design and intention, mine was not a leisurely trip. I drove home in installments. Traveling, slapping my map and trying to make sense of the transitions, I was constantly asking people directions. I always got help without any suspicion. My rental car's New York license plates aroused friendly curiosity all over the West and the South. At first I regretted that I did not know the South better; and then I began to think of this deficit as a travel opportunity, reflecting on the South as I had once contemplated parts of Europe or Asia: the dream of traveling through what was to me not just an unknown region but one that promised hospitality.

This feeling stayed with me all the way through the rolling hills to Nashville, where over lunch in a diner, I was greeted by the people at the next table, who saw I was alone and wanted me to feel welcome. I drove north on I-65, from Nashville into Kentucky. It was a special day in Owensboro, where a local man, Specialist Timothy Adam Fulkerson, killed in action near Tikrit, Iraq, was being honored: a section of U.S. 231 was being named for him, giving this country road a deeper meaning.

Kentucky, well tended and fenced, and the soft green of its fields and hills, the sight of horses and farms, made it seem an orderly Eden, parklike—another place to return to. This part of the state was rich in classic names—Lebanon and Paris, but Athens and Versailles had been tamed into "Ay-thens" and "Ver-sails."

One of the accidental themes of this road trip was my encounters with New Americans—the Iranian at the rental agency in Los Angeles, the Chinese gamblers in Las Vegas and my Ethiopian taxi drivers; the Somalis—robed, veiled, moving in a group of nine—I encountered in a Kinko's in Arizona; the man from Eritrea in Memphis, and here in Lexington, Mohamed from Egypt, in his convenience store.

"It's no fun to be single here if you're an Egyptian," he said. "But I'm married to a girl from Paris"—15 miles away—"and this is a good place to raise a family."

Passing the brick houses and quiet streets of Lexington, I continued through green hills, bumped along a corner of Ohio, and arrived in Charleston, West Virginia—a state capital that is more like a small town, with a population of around 50,000. I was in time for lunch at a Mexican restaurant. I merely happened upon it, as I found other good places on the road. Often, I asked a passerby— "Where's a great place to eat?" and I always got a helpful referral.

Ten days into my road trip I began wondering if I were perhaps pushing it a little too hard. But wasn't the whole point to keep going down the proud highway? The thrill is in the moving, gaining ground, watching the landscape change, stopping on impulse.

Then I met Steve the biker, out on I-79 at a rest stop, somewhere between Burnsville and Buckhannon, and he made me feel as though I had been dawdling. I had swung by for gas. Steve had stopped to adjust the strap on his motorcycle helmet. He had a new bike and was traveling from Omaha, Nebraska, to Alexandria, Virginia—in two days. He'd left St. Louis earlier that morning and had already traveled almost 600 miles—and was aiming to be home tonight, about 300 miles to go.

"I don't get it," I said.

"This is the newest Kawasaki," Steve said. "I can do 110 in first gear and I still have five more gears." He smiled a little. "I did 165 yesterday."

"And you don't get pulled over for speeding?"

"I'm a small profile," he said. "I'm under the radar."

Instead of following him up the Interstate, I turned east on mellow-looking Route 50 and meandered through Grafton, Fellowsville, Mount Storm and Capon Bridge—heading in the general direction of Gettysburg. I count the drive through West Virginia as distinctly memorable—there was hardly a town or village on the way I would not have been content to live in; not a hill I did not wish to climb, or a hollow that did not invite me to laze under a tree. At one point, bowling along the open road, the Supertramp song "Take the Long Way Home" came on the radio. Listening to music while driving through a lovely landscape is one of life's great mood enhancers. And hearing the line, "But there are times that you feel you're part of the scenery," I was in Heaven.

The rain in Gettysburg the next day provided a somber atmosphere for driving from battlefield to battlefield, from the carnage with the opening shots at McPherson's Ridge on the first of July, 1863, to the Battle of Little Round Top on the second day, to the futility of Pickett's Charge on the third and last day. I had dreamed for years of spending time in Gettysburg, a place of heroism, eloquent words and deeds. For a small fee, I had hired a friendly historian-guide from the visitors center, and he drove my car—the car that had brought me across America from Los Angeles. My two days in and around Gettysburg were perhaps the most vivid of the trip for the depth of history and the reminder that, as a nation, we are warriors as well as peacemakers.

No history book can equal the experience of walking those battlefields, where, in the paradox of warfare, a whole country was at stake because of the distance of a meadow or the length of a ridge or the capture of a little hilltop.

On my last day, I drove east through Pennsylvania on a maddening choice of roads that led home to Cape Cod. I was heartened by the sight of an Amish farmer plowing a field in shirt-sleeves, shaded by a straw hat, his daughter hurrying toward him with a bucket, like an eternal image in the tenacity of settlement.

In my life, I had sought out other parts of the world—Patagonia, Assam, the Yangtze; I had not realized that the dramatic desert I had imagined Patagonia to be was visible on my way from Sedona to Santa Fe, that the rolling hills of West Virginia were reminiscent of Assam and that my sight of the Mississippi recalled other great rivers. I'm glad I saw the rest of the world before I drove across America. I have traveled so often in other countries and am so accustomed to other landscapes, I sometimes felt on my trip that I was seeing America, coast to coast, with the eyes of a foreigner, feeling overwhelmed, humbled and grateful.

A trip abroad, any trip, ends like a movie—the curtain drops and then you're home, shut off. But this was different from any trip I'd ever taken. In the 3,380 miles I'd driven, in all that wonder, there wasn't a moment when I felt I didn't belong; not a day when I didn't rejoice in the knowledge that I was part of this beauty; not a moment of alienation or danger, no roadblocks, no sign of officialdom, never a second of feeling I was somewhere distant—but always the reassurance that I was home, where I belonged, in the most beautiful country I'd ever seen.

Paul Theroux's travel book Ghost Train to the Eastern Star is now out in paperback. His forthcoming novel is A Dead Hand.