Sugar and Spice in Colombia’s Alluring Cali

Candied treats and salsa music go hand in hand in this South American city high above the Cauca Valley

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cali-Colombia-skyline-631.jpg)

One thing about Cali I quickly realize: caleños are passionate people. They’re intensely proud of their traditions in a way that’s both disarming and contagious. Perhaps this has to do with what’s sometimes perceived as the city’s secondary status. Though it’s not quite as bustling as cosmopolitan Bogota or as picturesque as Medellin, Colombia’s third-largest city is the country’s economic and industrial hub, even if it is often overlooked by travelers. There is also the climate: situated 3,290 feet above sea level in the fertile Cauca Valley, the city maintains a year-round temperature averaging in the low 80s, giving it an endless summer atmosphere. And there is still the city’s unfortunate association with the Colombian armed conflict, which leads many caleños to fervently highlight their city’s offerings, like its impressive restaurants and world-class zoo.

It’s this passion and Cali’s developing tourism infrastructure that are inspiring many local entrepreneurs—such as Hector David Garcia, my interpreter for the day—to find new ways of attracting visitors. The single father spends his days driving cabs, tutoring history and running a tour company in the nearby city of Buga, where he keeps an apartment. Today, however, he’s gladly showing me the best that Cali has to offer.

The city has been known as the capital of salsa since DJs first coined the name of the music in the 1980s. The southwestern Colombian city of 2.5 million residents boasts nearly 100 salsa dancing schools within its greater metropolitan area, as well as hundreds of unofficial institutions. “This is likely the only part of the world where salsa is built into the culture,” says Luz Ayde Moncayo Giraldo, the Sondeluz Dance Academy's award-winning instructor and director, who teaches kids as young as 3 years old. A former systems engineer, the 43-year-old has students coming to her from as far away as Germany and Australia. Give her ten hours over one weekend, and she guarantees you’ll learn salsa. “You won’t become a world champion,” she says, “but you’ll be able to hold your own in a club.”

Despite its strong affiliation with local culture, salsa dancing didn’t become a way of life here until the late ’60s, when Colombians who had traveled to New York City returned home with LPs of salsa jazz musicians Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe. “People liked what they were hearing but couldn’t dance to it,” says Garcia, a 28-year-old Colombian who grew up with salsa. “So they adapted.” A blend of Cuban son and Afro-Cuban rumba moves influenced by Cumbia, Colombia’s national dance, Cali-style salsa is known for its quick diagonal footwork and still upper body. When they’re not learning the steps, Caleños are putting them into practice at one of the city’s many nightclubs in the historic Granada district—a fashionable area of restaurants, bars and boutiques—and in the outlying neighborhoods of Menga and Juanchito. “Salsa is in our blood,” says Garcia, smiling.

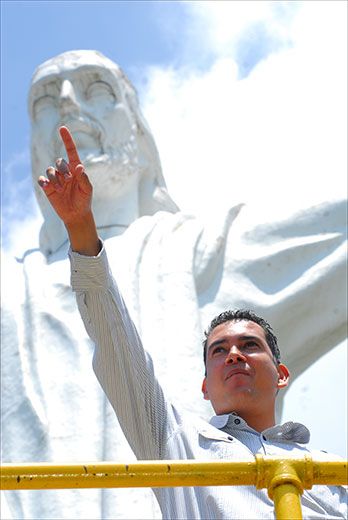

Though the city lies only 63 miles from the Pacific, it’s separated from the coast by the Farallones de Cali—part of the southern Andes mountains—which isolates it from the seaside humidity while providing a source of water and electricity through rivers and streams. The Cauca River runs along Cali’s eastern side, and midtown sits a somewhat chaotic expanse of modern high-rises, hotels, street vendors and shops. Cali also has its fair share of plazas, monuments (including a bronze statue of Spanish conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar) and interesting architecture, yet only a few truly must-see sights. One is Cristo Rey, a 101-foot-tall concrete statue of Christ standing atop 4,724-foot Cerro de Cristo Rey with his arms outstretched, presiding over downtown. Another is the historic district of San Antonio.

One of Cali’s most alluring neighborhoods, San Antonio is a walkable hillside community of narrow streets and old colonial homes—many painted in mustard yellow or tomato red—topped with clay-tiled gabled roofs. Unlike much of downtown, it feels largely residential but is home to some of the city’s best guesthouses, as well as cozy cafes perfect for lingering over empanadas and cups of Colombian coffee. I’ve come to San Antonio to visit the childhood home of Esther Otero Llanos, 61, who’s spending the afternoon here with her ten brothers and sisters making macetas, or candy trees. Though their origins are unknown, macetas are a Cali specialty, typically given to children on the Fiesta de Maceta each summer. Llanos’ mother, Sixta de Otero, spent more than 50 years producing and selling the confections—made from white sugar mass (alfeñique) and handcrafted into shapes such as clowns, birds and fish—and passed on her skills to her children. Llanos now sits with a few of her siblings at a large oval table, decorating individual sticks of the hardened taffy with colorful candies and streamers and then placing them into tiny holes on a foot-long wooden branch, which serves as each tree’s “trunk.”

They add a paper pinwheel, a flag and butterfly ornaments, and later sell the macetas at local markets for around 15,000 pesos, or $8.50 per tree.

If salsa runs through the veins of Caleños, then sugar is the beating heart. Belalcázar first introduced sugarcane to the Cauca Valley in the 16th century, and by the 1940s there were 22 sugar mills in the area. Today the region is home to 78 percent of the country’s 200,000 cane-growing hectares, and its consolidated mills contribute heavily to the country’s overall milling capacity of 76,000 tons of cane per day. About an hour outside the city in the municipality of Santa Elena is the Hacienda Piedechinche, a museum showcasing equipment used in the sugarcane industry since 1715. Everything from rudimentary mills to water wheels are on display along an outdoor walking path, which winds through an expansive garden of heliconias, palms and orchids. Cali is also known for its abundance of delicious sweets, including manjar blanco, a thick, caramel-colored milky pudding similar to dulce de leche, and guarapo, the pure juice of raw sugar cane.

On the drive back to our hotel to get ready for an evening salsa lesson with Moncayo, Garcia purchases a bag of chontaduros, another Cali staple, from a nearby street vendor. “Try it,” he insists, handing me one of the small yellow fruits. Despite its pungent smell, I bite into its pulpy flesh and am immediately surprised by the starchy taste, somewhere between the nuttiness of a chestnut and the heartiness of a smoked yam. It’s both unexpected and wholly satisfying. Much like Cali itself.