The Spice That Built Venice

The story of an import so prized, royals were literally rolling in it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/8d/c38dfa54-8fac-4182-8394-31612c110d59/sqj_1504_vencie_atlas_02.jpg)

In the year 1173 a bankrupt Venetian merchant by the name of Romano Mairano went looking for a way out of financial ruin. Over a trading career spanning several decades, Mairano had seen his share of ups and downs—latterly, more downs than ups. He could count himself lucky to be alive: Two years earlier, he had escaped a massacre of his compatriots in Constantinople, fleeing as his ships and goods were burned or confiscated. Back in Venice, safe but not sound—at least not in any financial sense—he was desperate. He decided to orchestrate a risky trade that could help him pay off his loans and restore his wealth, a trade for one of the most valuable commodities of the day: pepper.

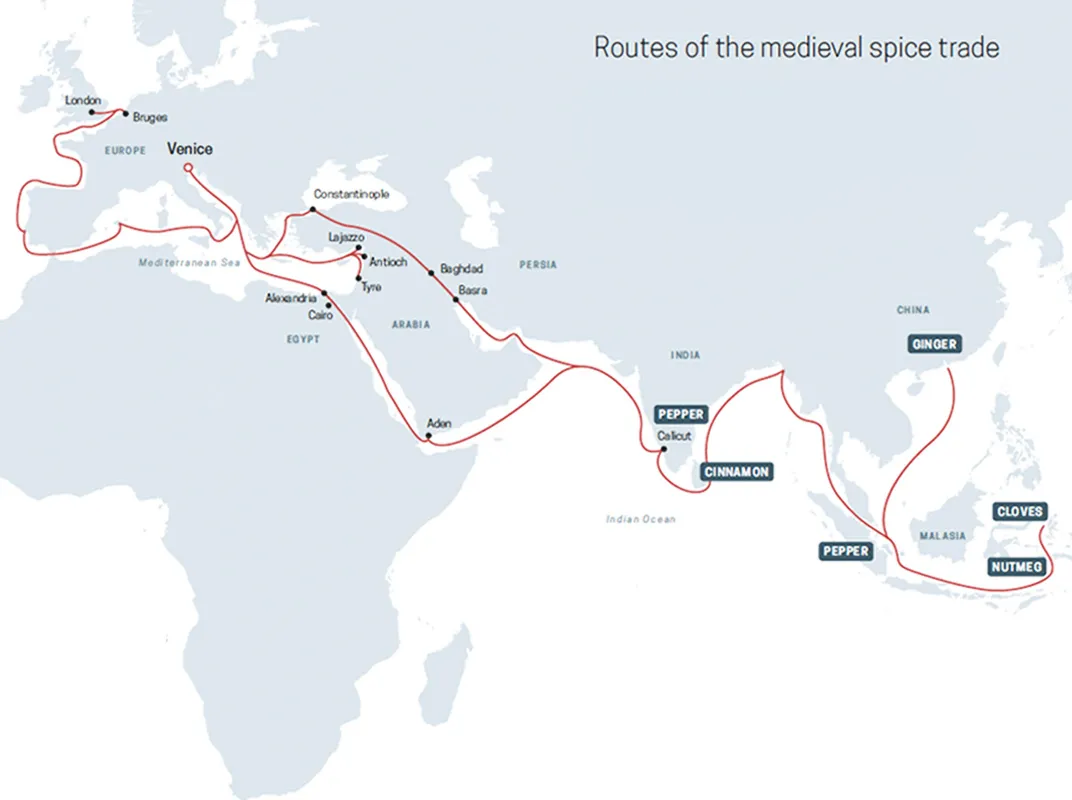

Mairano was bold but not crazy. Such schemes had enriched Venetian merchants for generations. Since well before the millennium, his forebears had sailed to Alexandria, the ancient Egyptian trading town at the head of the Nile Delta. By virtue of its access to the Red Sea trade routes leading to Arabia and beyond, Alexandria was the chief entrepôt between East and West, the point where fine luxuries such as silks, perfumes, gems, and, above all, spices arrived from the most remote parts of Asia. For the Venetian merchant courageous or lucky enough, Alexandria was the gateway to riches.

But if the rewards were great, so too were the dangers. Merchants ran the risk of attacks by pirates, and they were at the mercy of the volatile, violent politics of the age. No insurer backed their cargoes; no coast guard patrolled the seas. They had to outmaneuver Venice’s perennial enemies and competitors, the Genoese. And Mairano would be doing business in a Muslim country nominally at war with Europe—its ruler none other than Saladin, who would later defeat the Crusaders.

On this occasion, the gods of commerce smiled on Mairano. With money borrowed from a wealthy friend, he shipped a cargo of lumber to Alexandria, and in return he brought back spices. He was finally able to repay his creditors—not in cash, but in pepper. The remainder of the spices he sold in Venice at many times the purchase price.

**********

To understand how Venice became such a glorious city, it pays to look south and east, just as Mairano did. Over the course of a long career, Mairano, like countless other traders, had a stake in many deals: for timber, slaves, textiles, wine, ships, grain, metals, and more. But for reasons of simple economic alchemy, spices were the marquee good. As they moved between the jungles of South and Southeast Asia, where they were harvested, to their final points of sale in Europe, the value of spices mounted exponentially. They were small, readily transferable, durable—and immensely desirable.

Medieval high society had an insatiable appetite for spiced sauces, sweets, wine, and ale—not, as was long believed, to cover the taste of old and rotting meat, for spices were far too expensive for that. No less than in our day—indeed far more so, given the acutely hierarchical nature of medieval life—eating was as much about making an impression as enjoying flavor. And of all the spices, pepper was far and away the most important, for its consumers and Venice alike.

In Mairano’s era, Venetian traders in London sold a pound of pepper for a sum equivalent to a week’s work for an unskilled laborer. Cost alone ensured that pepper was as much an attribute of high rank as castles and coats of arms. Kings and wealthy prelates cured their ailments with pepper. They carried peppery pomanders to ward off pestilence, and went to their graves embalmed in myrrh and pepper. The most eminent medical authorities of the time insisted that pepper could revive flagging libidos. Around the year 1100, one Duke William of Aquitaine boasted of a week-long ménage à trois, claiming his exertions (188, no less) were fueled by a hearty dose of the spice.

Once spices arrived in Venice, they were unloaded for distribution across Europe. Some were resold directly to merchants arriving from the north. Others were shipped on barges up the Po Valley, and carried on mules across the Alpine passes to Germany and France. Venetian galleys sailed past the Strait of Gibraltar and onward to London and Bruges. As often as not, the cinnamon in a duke’s pomander or the ginger in an abbot’s medicine chest or the pepper appearing on a king’s table was at some point freighted and sold by a Venetian.

**********

As with any successful business, location was key. By virtue of Venice’s ties to Byzantium, from the city’s earliest days Venetian merchants had had privileged access to the overland trade routes to Asia. When the French saint Gerald of Aurillac passed through the northern Italian town of Pavia around 894, he met a small group of Venetian merchants selling cloths and spices from Byzantium.

In due course Byzantium’s energies faltered, and the relationship with Venice became increasingly hostile. By the year 1000, Venice opened another route to the Orient by concluding treaties with the Muslim rulers of Egypt and the Levant, safeguarding the position of its merchants in Islamic lands.

As the medieval European economy grew, the spice trade grew with it. The largely ad hoc voyages of Mairano’s day gave way to a regular system of convoys known as the muda, or state-subsidized galleys auctioned out to the highest bidder. No spices were allowed in the cogs, round ships, or carracks that were the workhorses of maritime trade. Rather, they were whisked across the sea in armed fleets carrying up to 300 metric tons of spice, defended by a contingent of marines, and sped on their way by banks of rowers, swift enough to outrun any pursuer.

Pirates and other raiders were not the only obstacles, however. Venice’s dealings with Muslim rulers sat uneasily with the Roman Catholic powers of Europe and particularly the papacy, which remained, with varying degrees of ardor, wedded to the ideal, if not necessarily the practice, of Crusade. So it was that in 1322 a papal envoy arrived with the news that many of Venice’s leading citizens had been excommunicated as punishment for having violated papal bans on trading with the infidel.

The sequel to this story nicely illustrates the Venetians’ gift for navigating the tricky shoals of religion, geopolitics, and finance. While vigorously protesting the excommunication, the signoria complied with the papal diktat, halting direct voyages to Alexandria. Yet trade was simply diverted to the Armenian port of Lajazzo, a tiny Christian enclave tucked into the angle formed by Anatolia and the Levantine coast. Here the Venetians could acquire the very same spices they had previously purchased directly from the sultan, knowing full well that Lajazzo’s spices had been subjected to the same taxes, tolls, and levies imposed by the region’s Islamic rulers. No matter. Any moral peril was neatly transferred to the Armenians.

Business was business, and Venice’s papal problem was neatly defused. In due course, a few decades after the pope’s envoy had dropped his bombshell, the Venetian galleys were once again loading their precious cargoes of spice at Alexandria. No one was seriously inconvenienced—no one, that is, beyond Europe’s consumers, who for a time paid a little more for their pepper.

Bad news came in 1501, however, when word reached Venetian merchants that the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama had sailed around Africa to India, bypassing the Mediterranean and—so it was feared—diverting the flow of pepper away from Venice. As it happened, it would be another century or so before the rivers of spice would finally run dry, during which time the city became increasingly forgetful of the traffic that had once bankrolled its beauty. In some of the majestic, sun-drenched canvases of Canaletto, you might glimpse merchant galleys in the background, but the 18th-century painter showed no interest in the cargo they bore.

Yet even today in one of the city’s bakeries you might find a peverino, a type of peppered cookie, relative of the better-known panpepato and panforte—spiced, honeyed confections that date to the Middle Ages. Or take a walk down the elegant colonnades of the Ruga dei Spezieri, the “street of the spice merchants.” There in the bustling market, among the tourists and Venetian vendors happily pocketing their money, you may hear the faintest of echoes of the commercial energies that once helped build a glorious city.

More from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly