These Photographs Capture Cuba’s Fading Cinema Culture

In a new book, photographer Carolina Sandretto focuses on a piece of the island’s heritage that is often overlooked

Cinema culture has had a longstanding history in Cuba. Before the Cuban Revolution took hold of the island nation in the 1950s, Cuba was home to more than 500 cinemas—more than New York City or Paris at the time. Soon thereafter, the number of halls increased to nearly 700, with many of them constructed and managed by major film studios like 20th Century Fox, Columbia Pictures and MGM. At a time when social outlets were severely limited by a controlling government, going to the cinema became an important pastime for Cubans.

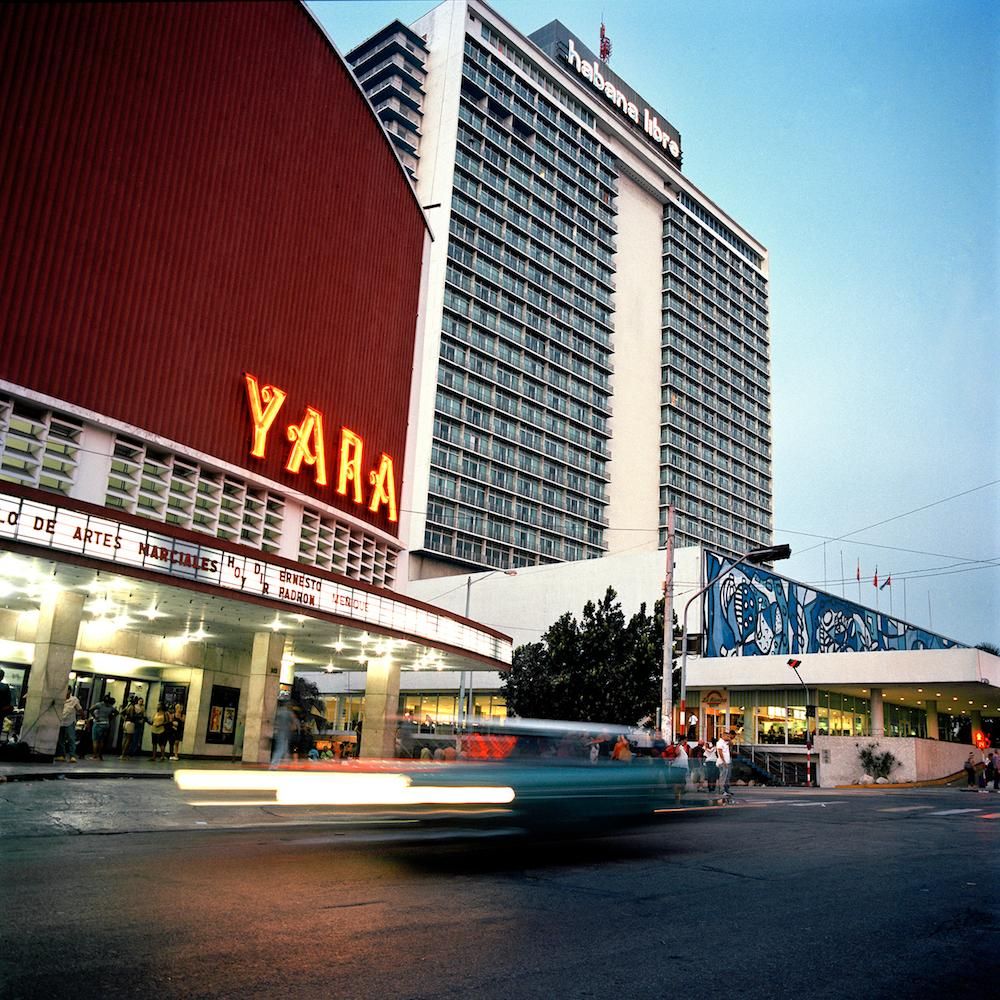

Over the years, time and lack of funding have taken their toll on these historic structures, and today only a handful of theaters remain in use for their original purpose, while others either have been repurposed or sit in various states of decay. These architectural reminders of yesteryear are what stoked Italian photographer Carolina Sandretto’s interest in Cuban cinema culture. Over the course of four years, Sandretto traveled from village to village and photographed more than 300 cinemas built throughout different eras, from Principal in Sanctu Espiritu that opened in 1839 (rumor has it that locals helped carry the wood for its roof for 13 miles) to Avila in Ciego de Avila, built in the 1960s.

“Every time it was a surprise for me to find another cinema almost always different from the ones I had seen before,” she writes in the book’s opening essay. “I decided to make portraits of the constructions both inside and out. Scars, remodeling, abandonment—like living creatures they all had a personal history to tell and the stories they lived through are visible on them.”

In her book Cines de Cuba, published by Skira this month, Sandretto brings these structures back to life for one last curtain call.

Why did you choose cinemas in Cuba as the focus of your book?

I was already in Cuba before I started working on this book. One day I was walking through a small village and saw this beautiful cinema and took a photo of it. I asked my guide how many cinemas there were in Cuba, and he wasn’t sure, so I did some research and found a book from 1963 called Anuario Cinematográfico y Radial Cubano, which published a list of all the cinemas on the island. I discovered that the number of cinemas was impressive and in the hundreds. So I decided to make the island of Cuba and its cinema culture my focus, since it’s a reflection of how we consume media nowadays. We used to go to the movies; it was a social thing and something we would share with our community, but it’s not like that anymore.

Cines de Cuba: Photographs by Carolina Sandretto

In 1953, Cuba had 694 cinemas and theaters. Havana alone had 134, more than New York or Paris. In 2014, New York–based documentary photographer Carolina Sandretto set out to find and photograph, with a 1950s medium-format camera, the remaining cinemas from that golden era. This book is the visual document of her journey.

At one time there were more than 600 cinemas in Cuba, but now there are only 19 still in operation. What happened?

When the Cuban Revolution happened, a lot of cinema owners decided to leave the island. The government took over operating their businesses, but running that amount of cinemas was absolutely impossible, so the number of cinemas slowly decreased. The 19 that remain have been updated to today’s digital world, but many of the others have been abandoned or converted into community centers, places for the elderly and centers for kids. Unlike other countries where cinemas were destroyed to make space [for new buildings], in Cuba, because of the historic bubble and the fact that there was no money to be spent on [these projects], a lot of the old cinemas are left standing.

Why was film such an important part of the cultural fabric of Cuba at one time?

Cubans love cinema and they love going to the movies, and, generally speaking, they have an incredible cinematic culture. They’re also producing a lot of cinema and have a very competitive cinematography school, so they’re very affectionate toward movies as a society. This needs to be blended with the fact that years ago [one of the few social activities in Cuba] was going to the movies. It was the one place where you could go and meet people, since Cuba didn’t have a culture of going to bars and pubs like other countries did at the time.

Some of the theaters you captured on film are like stepping back in time. Were there any in particular that stood out to you?

All of them have their own stories, but the ones that stood out to me are linked to beautiful stories that happened while there. At one cinema, Cine Beli in Contramaestre, a province of Santiago de Cuba, I saw a group of schoolchildren in their uniforms. The teachers were trying to calm them down because they were so excited to be there, so I shouted and they all turned around, looked at me and sat down. The teachers were so amazed that they listened to me, a stranger, that they let me take all the pictures I wanted. Another time in Havana I visited Cine Majestic built in 1911, with a roof that could be opened, so at night you would have fresh air coming in. To me, it’s amazing to have a building at that time with a retractable roof. There are also a lot of cinemas with incredible Art Deco touches that look similar to what you might find in Miami, as well as opera houses that are designed after opera houses found across Europe.

In your book, you also mention the challenges to finding where cinemas once stood on the island, since there are no online records. How were you able to source the information that you needed?

One of the key ingredients [for this book] was to go to the different villages and talk to an elderly person, since they were the ones who were going to the cinema back then. They have knowledge that young people wouldn’t have, such as if a cinema had been destroyed. [Because of Internet censorship in Cuba], I couldn’t run a web search to find information, so I also used the Anuario Cinematográfico y Radial Cubano booklet, which lists all of the cinemas, the number of seats at each one and the owner’s name.

Are there any efforts on the island to help preserve what’s left of the cinemas that remain?

Not that I know of. There [is] one cinema named Cine Encanto in Camaguey where a couple has asked the government if they could have exclusive rights to use it. It’s now refurbished, and each year it hosts a contemporary arts video festival. I wish there was an organization that took care of the cinemas. One thing that I hope my book does is to help the government realize that it has an incredible thing, and that it should make a fund to sustain these buildings.

Why is it so important to document Cuba’s cinema history?

Cuba is a very peculiar place, and it has had a lot of different influences and different types of architecture. You have the first opera houses, then cinemas from the early 1900s, then the Art Deco era, and then the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s—plus all of the future transformations of these buildings. It’s extremely interesting from an architectural point of view. For example, The Fenix cinema is Art Deco, and it's now a living space. Also, The Ambassador is from the 1930s, and it was revived in the 1950s. [At one time it had] a huge neon [sign] with its name on top of the building, but that has been destroyed. Overall, Cuba hasn’t had the chance to change [politically] throughout periods of time, so all of these different cultural contaminations [such as the architectural details related to each era] make it a very interesting place. There’s an incredible heritage there and to see all of these different types of architecture in one place, I just can’t think of another place in the world that has a similar spectrum of architecture.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.